Ian Verrender* says central banks are draining money out of the economy and asks if they will pull more banks down the plug hole.

Chaos, contagion, calamity. The doomsday calls have been coming thick and fast during the past fortnight, replete with predictions of a global financial crisis re-run.

Chaos, contagion, calamity. The doomsday calls have been coming thick and fast during the past fortnight, replete with predictions of a global financial crisis re-run.

The collapse of two American banks, the industry bail-out of a third and a run on smaller regional banks sparked panic among stock investors.

That just happened to coincide with yet another disastrous episode in the decade-long train wreck that is Credit Suisse on the other side of the Atlantic.

An unfortunate coincidence, perhaps, that combined to wipe around half a trillion US dollars from the value of banks.

There is, however, no denying that the torrid round of interest rate hikes — the pace of which has been unprecedented — has rattled the foundations of global finance.

And while the European Central Bank shrugged aside the warnings and pushed ahead with a super-sized rate rise last Thursday — for fear of appearing concerned about the week’s events — there’ll be plenty of questions in central bank boardrooms about the wisdom of future hikes and the speed at which they should take place.

There’s an old saying about interest rate hikes: The Fed will continue raising rates until something breaks.

Are the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank collapses evidence that something has broken? Probably not yet.

But they are a timely warning that rapid changes in monetary conditions can have sudden unintended consequences that lead to the kind of chaos, contagion and calamity that we witnessed 15 years ago.

Rate hikes have dominated the discussions until now.

But another more insidious danger lurks as central banks deliberately attempt to drain the global financial system of the cash they injected during the pandemic.

More on that later.

Money and faith

Here’s a quick quiz: Name the riskiest companies on the Australian Stock Exchange.

If you answered with the names of a couple of penny dreadfuls, a few cash strapped gold explorers or even a tech venture, you’d be wrong.

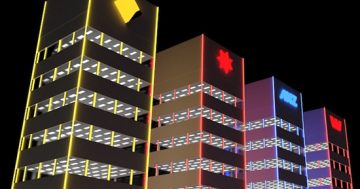

The correct answer would be our banks, starting at the smallest and heading for the biggest.

That’s not to say there is anything particularly wrong with Australian banks, apart from their huge over-reliance on real estate.

It’s just that most folk don’t realise is that banking is the riskiest business of all.

Why? Because they operate on relatively small capital or equity bases compared to the size of the debts they carry and their commitments to depositors.

Another thing that isn’t widely understood is that commercial banks are responsible for the creation of the vast bulk of our money.

They don’t just lend out the money they take in on deposit.

Each time they make a loan, they are creating money out of thin air.

It isn’t the government that creates our money.

Or the Reserve Bank of Australia.

They can and sometimes do.

But around 97 per cent of our money supply comes from the banking system.

The Reserve Bank’s primary role is to either speed up or slow down the speed at which our commercial banks create cash which, in turn, affects our economic growth.

That’s done through interest rate adjustments.

Unlike almost any other industry, banking overwhelmingly is built upon trust: an assurance that you’ll be able to retrieve your cash when you want it.

But in a system that is so leveraged and so highly geared, even minor ructions can quickly undermine that trust.

Maybe America’s founding fathers knew more than they were letting on when they had “IN GOD WE TRUST” printed on the greenback.

Australian exceptionalism, maybe not so much

You’ll be hearing plenty of assurances in coming months about just how strong and how well capitalised our banks are.

That’s absolutely true.

But Australian banks are plugged into the global financial system and when things go wrong elsewhere, it impacts here.

There’s a commonly touted myth that our banking system sailed through the global financial crisis unscathed.

That’s just rubbish.

BankWest failed and was snapped up by Commonwealth Bank.

St George was placed under the umbrella of Westpac.

Suncorp was on the ropes and about to be offloaded to another Big Four but was saved after the federal government guaranteed the debts of all our commercial banks, following furious lobbying from a then-beleaguered Macquarie Bank.

A few years earlier, in the early 90s, Westpac almost came asunder after a meltdown in the value of its commercial property portfolio.

When the system is flush with liquidity, when the machinery is lubricated by trust, things generally go swimmingly.

But if that faith is dented, and everyone wants their cash at the same time, few banks have enough on reserve to make good.

That’s why governments invented central banks.

Before they became masters of the global economy, their primary role was as “lender of last resort”, to ensure deposits could be recovered and stave off a catastrophic loss of confidence that would damage the economy.

The global financial crisis was created by lax oversight of a deregulated banking system and made worse by the US Federal Reserve’s decision to allow Lehman Brothers to collapse.

It’s not about to repeat that mistake.

That is why it swiftly guaranteed the deposits of both Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank last week.

The shareholders will lose everything.

But the banking system fallout so far has been muted.

It’s a similar story on the other side of the Atlantic.

Rival bank UBS, which has had its own share of problems since the GFC, has negotiated to absorb the sinking hulk of Credit Suisse, taking over the company with the backing of government guarantees in a deal that includes 100 billion Swiss francs ($160 billion) in liquidity assistance.

Cracks in the system

Rate hikes are supposed to hurt.

They’re designed to slow down growth.

That creates casualties.

Last year, once high-flying technology stocks swooned as money shifted out of high-risk ventures and gravitated to safer harbours.

The great crypto con was the first to founder and those that financed it ran into a brick wall.

Signature Bank was heavily involved in crypto loans while SVB focused on technology entrepreneurs, enterprises and investors.

As the deposit withdrawals accelerated, neither bank had adequate reserves to meet them.

A major problem with SVB was that the US government bonds it had used as security had been devalued by the US Fed’s rate hikes.

But, because of an accounting loophole, they hadn’t been written down or discounted in the accounts.

When the crunch came — after a ratings agency decided to downgrade SVB’s credit ratings — it didn’t have enough to cover the run on deposits.

Investors, concerned about similar practices elsewhere, quickly began abandoning smaller regional banks.

Stock prices last week tanked as trust evaporated and fear took hold.

Tech and crypto were early casualties.

Given soaring real estate values across the globe during the past few years, there would be plenty of worried bankers about the sudden declines in real estate.

The unspoken fear

You may have heard of Quantitative Easing.

It became the topic du jour during the pandemic as central banks essentially printed vast quantities of cash to inject liquidity into a system they thought might seize up.

Even the Reserve Bank of Australia — which for years swore off the practice — jumped on board.

The Bank of Japan was the first to engage in this in the late 90s in an effort to kickstart its moribund economy.

America launched into it during the GFC but went hell for leather during the pandemic.

Right now, the US Fed is trying to do the opposite, a process called Quantitative Tightening.

Essentially, it’s trying to drain the financial system of cash, of liquidity right when it is jacking up rates at a phenomenal speed.

And that spells danger.

This graph shows the level of assets the Fed holds or has bought in the past 15 years, just shy of $US9 trillion ($13.3 trillion).

That’s how much it has pumped in.

Draining the system

The downturn on the right hand side illustrates how quickly it now is attempting to drain cash out of the financial system.

The problem is … it’s never been done before, at least successfully.

The Fed failed to do it after the GFC, waiting until 2018 to finally have a crack at it.

But each time it attempted to retrieve the cash, various corners of global money markets went haywire.

Then the pandemic hit and it reversed course, opening the liquidity sluice gates like never before.

The US Fed is now draining the system harder and quicker than during its failed effort in 2018.

But it has no real model or framework to help guide it in this hugely dangerous quest.

The speed of rate hikes already is in unprecedented territory.

Add to that, a program of Quantitative Tightening that has never been successfully undertaken and it dramatically increases the chances of a serious breakdown in global finance.

It isn’t like it’s never happened before.

*Ian Verrender is the ABC’s Business Editor.

This article first appeared at abc.net.au