Bethany Schoer* says she’s reconciling the loss of her professional ambition as an Asian woman.

Australia’s latest round of census data has revealed that people of Asian descent are far from being in the minority.

Australia’s latest round of census data has revealed that people of Asian descent are far from being in the minority.

Three out of the five top countries of birth were located in Asia, while the most common foreign languages spoken at home were Mandarin, Arabic, Vietnamese, Cantonese, and Punjabi.

Yet despite these figures, the concept of what it means to belong to an Asian culture continues to be reduced to a series of stereotypes that focus on our status as workers rather than as fully-functioning people.

It’s not difficult to see that Asians have been historically portrayed as sidekicks whose value to society has been determined solely by intellect and passivity.

Where Asians have been given a voice (or an approximation of one), it has often been through the mocking, ill-informed lens of Western subjects who present us as little more than a source of novelty and comic relief.

It is important to note that aspects of the smart, hardworking, and discrete stereotype also exist within Asian communities themselves, too, driven in part by the need for survival and broader social acceptance.

There is the well-worn narrative of the ancestor whose endless sacrifices involving long hours, inhumane working conditions, and racist taunts have elevated them to demigod status among their children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren.

To this day, their lives serve as a blueprint for how future generations should live and as a reminder to be prepared to make sacrifices of their own.

As a half-Asian person, I’ve discussed this at length with my Asian friends and we have agreed that doing well in school and university and then finding a stable, well-earning and respectable job is a baseline expectation among our communities.

Academic and professional success is framed as our raison d’être, and ultimately becomes linked to our self-worth.

But what happens when we decide that professional success and ambition no longer deserve the pedestal on which we, and our communities, have placed them?

I had this realisation somewhere around the start of 2021, interrupting years of good grades, accolades, and praise from teachers, coworkers, and family members.

Perhaps more crucially, it slowed the negative physical and mental impacts of a lifetime of chasing perfectionism and external validation.

This realisation triggered an identity crisis which raised two key questions.

Firstly, who am I outside my academic and professional achievements? And secondly, does letting go of future professional success fly in the face of my family’s sacrifices, and in turn, make me a bad Asian?

The more I questioned whether my work in a highly competitive, respected industry was truly giving me the satisfaction I craved, the more I felt like I was driving away from my Asian family and waving to my late grandfather, or Goong, in the rear-view mirror (very ironic considering I can’t actually drive).

Guilt naturally bubbled to the surface after I handed in my letter of resignation for what had once been my dream job.

I couldn’t help but feel like I was throwing away years of my own hard work, and perhaps most significantly, the hard work of relatives from generations past which had allowed me to succeed in the first instance.

About a month later, I can see that this guilt is starting to morph into a quiet hum of self-assurance and curiosity, which has encouraged me to seek out a more multidimensional understanding of my cultural identity.

My mixed-race identity and ability to ‘white-pass’ have only complicated this issue.

As someone with a Chinese mother and white Australian father, I’ve been fed messaging about needing to choose between my Asian or my Caucasian heritage.

Any failure to choose would result in my “white side” winning out based on my looks alone.

On a day-to-day basis, this has led to me loudly overusing the words “Mum” and “mother” whenever I’m out with my mother in public in an attempt to be seen for who I am: as half-Asian.

More broadly, I have extended myself academically and professionally to prove my cultural identity in ways that my appearance could not.

I have maintained the belief up until recently that a commitment to academic and professional growth would somehow make me a more believable, legitimate, and better Asian.

Over the past 30 years, I’ve grown from a docile, results-oriented girl into an outgoing, candid feminist armed with the symbolic belief that no one will heap praise on your email writing skills when they’re delivering your eulogy at your funeral.

I don’t see this as a departure from my cultural identity as much as I do a manifestation of the bravery, strength, and authenticity of previous generations of Chinese women with whom I share my roots.

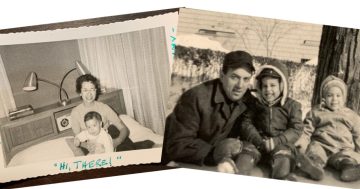

Fully and shamelessly inhabiting all parts of myself celebrates my late grandmother, whose love of writing I inherited and who struggled through a terminal illness in the hostile milieu of Australia in the 1970s.

It celebrates my late aunt, who, despite her personal hardships and fractious relationships, took the leap to become a transgender woman and in turn, live a life in line with her identity and values.

And it celebrates my mother and her two remaining sisters and the glorious cackles we share when we’re all gathered around the table exchanging embarrassing stories from our childhoods.

I can take heart in the fact that the blood of these women, and the blood of my Asian ancestors in general, runs through my veins.

This won’t change regardless of how many hours a day I toil away at my desk or how many work promotions I secure.

Overall, I’ve realised that being Chinese, Asian, or a person of colour doesn’t depend on ticking a satisfactory number of boxes informed by an arbitrary mix of intergenerational sacrifices and stereotypes perpetuated by the media.

The idea of a “‘Bad Asian”, a “Good Asian” or anything in between only serves to reinforce problematic ideas at the expense of a person’s authentic feelings about themselves, their communities, and their growth.

I have always been Asian before I was ever a student or an employee, and no messaging can diminish this.

As I pursue this next chapter, I’ll take pride in the fact that I stepped away from cultural and societal expectations for the sake of my mental health — all while helping Mum distribute red packets in between mouthfuls of ma lai gao.

*Bethany Schoer is a contributor at Refinery29.

This article first appeared at refinery29.com.