Pia Rowe* discusses how the few years preceding the federal election brought about a new ear in Australian politics.

“A hundred or so years ago, there was a woman called Vida Goldstein. She was an internationally renowned suffragist. She was the first Australian in the oval office.

“A hundred or so years ago, there was a woman called Vida Goldstein. She was an internationally renowned suffragist. She was the first Australian in the oval office.

“She ran as an independent several times because she was so independent, that she couldn’t bring herself to run for either of the major parties.

“Vida was not elected. This seat is in her name. And today I take her rightful place.”

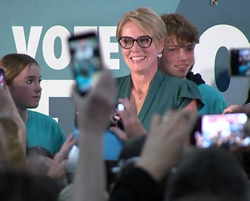

Zoe Daniel, 22 May 2022

When it became clear that the Independent candidate, Zoe Daniel (pictured), was going to win the seat of Goldstein, held by the Liberal Party since its inception in 1984, it was hard not to become emotional.

The ‘teal wave’ sweeping through the nation as a result of the Australian 2022 Federal Election brought with it new hope for the future.

Along with Daniel, Allegra Spender in Wentworth, Kylea Tink in North Sydney, Sophie Scamps in Mackellar and Monique Ryan in Kooyong, all signalled a new era, in which professional women take seriously the women’s vote, and the issues that matter to them.

Among the many joyful moments of the election night, few topped the historic occasion when Linda Burney was set to become the first Indigenous female Minister for Indigenous Affairs.

Just before the election, an article in The Sydney Morning Herald posed the question, ‘Where has the women’s rage of 2021 gone?’.

Juxtaposing the loud and visible protest movements of the previous year with the relative silence of 2022, it sought to understand the current landscape for women’s issues.

So was it anger that got us here? Or something different altogether?

Rage can be powerful – if problematic if you’re a woman, or a person of colour, or really, anyone other than an old white male called John or Peter or David.

There is little doubt about the role of anger as the underlying force of the major shift in both the candidates and the voters.

The repeated failure of Morrison’s government to listen to the nation ultimately became its own undoing as the people fed up with the lack of representation in the overwhelmingly white and male Liberal party took to the polling booths.

As Liberal frontbencher, Simon Birmingham argued, “gender, diversity and climate change were clearly factors in the election results”.

But here’s the thing.

Rage in its purest form also promotes division.

As we’ve witnessed in recent years, the traditionally adversarial nature of Australian politics has done nothing to unite the increasingly polarised society.

Emotion may well be the catalyst and the motivation for political action, but for it to be sustainable in the long term, it needs to be harnessed in a manner that promotes collegiality and consensus, not drive us further apart.

From a very young age we are taught how to debate a topic at school.

And debates, by their very nature, have a winner.

But what if instead of winning or losing, we focused on how to discuss and deliberate with others, not so that we can win the argument, but to reach a point where we’ve exposed ourselves to differing views, and reflected on our own stance?

Academics and politicians worldwide have seen many a polarising issue – from marriage equality to abortion, and to genome editing – rationally deliberated on by ordinary and diverse citizens from different backgrounds in highly controlled settings.

While such formal proceedings are of course not suitable for solving the regular day-to-day issues, the key takeaway is this: If 99 randomly selected people can discuss a difficult topic in a respectful manner and reach a point where they can make recommendations for future policies, then surely the very people elected to represent the society can also find new and productive ways to work with both one another, and the constituents.

Professor Nicole Curato from the Centre of Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra has been researching the role of deliberation in politics for over a decade.

She explains:

“Deliberation allows us to clarify the extent of our disagreements and advance plausible political projects despite our differences.

“It encourages us to carefully think about our views and take the perspective of those whose views we don’t share.”

Professor Curato also highlights the increased accountability that comes when the rules of the debate shift from yelling your opponent down to actually crafting an argument that stands the scrutiny of reason.

“Deliberation asks us to justify our reasons to others, and, in so doing, it gives us the change to spot the weaknesses of our arguments.”

It takes a lot of guts to pause and look in the mirror in the middle of a heated debate, and acknowledge that the reflection is not perfect.

For far too long, the winner-takes-it-all blood sport that we call politics has been devoid of even the cursory manners – and that is to put it mildly.

All too often, the reports of the toxic nature of the Parliament as a workplace have been dominating the headlines in recent years.

But the time for mud-slinging is over.

On Saturday 21 May 2022, women in Australia roared.

But instead of rage, they roared with reason.

Compassion.

Sensible policies and politics.

And they made history.

*Dr Pia Rowe is a Research Fellow at the University of Canberra.

This article first appeared at broadagenda.com.au.