Roger Crisp* says insight from the great philosophers of the ancient world could help guide our response to the climate crisis.

As world chiefs and youth leaders gathered in New York at the United Nations Climate Action Summit, many of us as individuals were left feeling powerless and overwhelmed.

As world chiefs and youth leaders gathered in New York at the United Nations Climate Action Summit, many of us as individuals were left feeling powerless and overwhelmed.

Making big personal changes can appear costly in terms of happiness.

And anyway, why should I bother when any difference I can make will be negligible?

As we contemplate our future, we can seek insight from the great philosophers of the ancient world to guide our choices.

Virtue

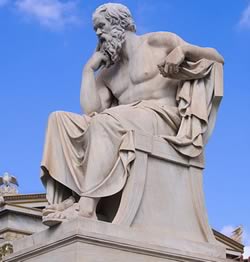

Socrates wrote nothing, but many of his ideas found their way into the dialogues of his star pupil, Plato.

The main character in these dialogues is indeed Socrates himself.

In Plato’s most famous work, The Republic, Socrates suggests that he and those around him discuss the most important question there is: how should one live?

One of his interlocutors rather aggressively suggests that the answer is obvious: you should do anything that gives you money, power, and pleasure, and ignore all the constraints of so-called morality, which is just a con dreamed up by the powerful to keep us in our place.

The conflict between the personal goods that Thrasymachus (a sophist and character in The Republic) lists and virtue — or doing what’s right — is at the heart of the climate crisis.

Should I take this highly paid job with an international oil company, or work for a local environmental charity?

Shall I buy a new SUV, or donate the money and put up with the inconvenience of public transportation?

A harmonious soul

Socrates has some snappy responses for Thrasymachus, but they don’t really work, so he starts to develop a more sustained argument based on the idea of “the soul” — that set of qualities that makes us the kind of living beings we are.

There are three main aspects to the soul: reason, desire, and spirit (or emotion).

Socrates suggests that the best souls will have reason in charge, shaping and directing the desires with the help of the emotions.

So, though I may want to be sitting right up there in that SUV, feeling powerful and loving the admiring looks I get from passers-by, what I should ask is whether this is what I have strongest reason to do.

Thrasymachus will of course say: “Obviously, yes!”

But Socrates compares souls to cities, and he compares the souls of people like Thrasymachus, who follow their desires wherever they lead, to tyrannies.

While it might seem great to be a tyrant, Socrates predicts that tyrants will slide into a frenzied search for ever greater power and pleasure, never tasting true freedom or friendship.

His idea is that you are essentially a rational being, and if you are led by your desires then you are not actively living a life at all.

Politicians, take note.

The apparent conflict between personal goods and virtue, then, is only apparent, since you will not be truly happy without virtue.

And there does seem to be some modern support for the Socratic view from modern “positive psychology”.

This relatively new field suggests many people who care about others and commit themselves to moral goals report higher wellbeing and a greater sense of meaning and purpose.

Having this sense of life’s purpose has even been associated with a lower risk of death.

The doctrine of the mean

But at a time when change is needed, how do I decide exactly what the virtuous thing to do is?

Here we can learn from Plato’s most famous pupil, Aristotle.

Aristotle sees that human life consists in various spheres, and that each sphere can often be characterised in terms of a feeling or an action.

Take anger.

To live virtuously, you have to feel anger in the right way — at the right time, for the right reasons, towards the right people and so on.

And there are two ways you can go wrong, by feeling anger in the wrong way, or by failing to feel anger in the right way.

The moral life, then, consists in our attempt to hit the sweet angry spot between the two ways that anger can go wrong.

The analysis works in the same way with actions.

Generosity is to do with giving away money, and that should be done in the right way.

If you don’t do it in the right way, then you are stingy; if you do it in the wrong way, then you are wasteful.

In terms of our climate, this relates to the releasing of carbon dioxide.

So, the central environmental virtue is eco-sensitivity.

Someone who releases carbon in the wrong way (leaving their engine running while they visit the shops, for example) is eco-insensitive, and there might also be cases of eco-oversensitivity (refusing to call an ambulance, say, for someone who needs urgent help).

Aristotle notes that we are often more attracted to one particular vice, and here that is of course eco-insensitivity.

What we should do, then, is reflect on our own practice.

If we think we are tending towards that vice, we should try to come closer to the mean.

We don’t have to aim at perfection.

We can take one step at a time in the right direction.

And — if Socrates is right — we will find that you have not sacrificed much, if anything, of your happiness as you do so.

Modern virtues

Since ancient times, other virtues have been added to the list, and hope is another important virtue in facing the environmental crisis.

The ancients did not really consider cases in which a group of people are doing something terrible, though each individual’s contribution makes no perceptible difference.

One of the central environmental virtues here is collaborativeness, which leads us in the direction of political as well as personal action.

We are also more aware than the ancients were of the moral significance of allowing things to happen, as opposed to actually doing something about them.

We need to take “negative responsibility”, not just stand by and watch as our planet is damaged.

Virtuous action is needed, from the individual up.

But by looking to the ideas of the ancient philosophers we can recognise that, at least as far as the climate is concerned, morality requires only small shifts in each moment rather than the seismic shifts that many might fear.

* Roger Crisp is Professorial Fellow at the Dianoia Institute of Philosophy at the Australian Catholic University and Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com.