Reviewed by Robert Goodman.

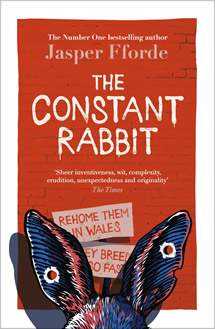

By Jasper Fforde, Hachette.

It is not very far into The Constant Rabbit that readers familiar with Jasper Fforde’s work will know, without doubt, they are in a Fforde novel. And it does not even take the appearance of a human-sized talking rabbit. No, it is the group of local English villagers, code-named for British prime ministers, for obscure reasons, who volunteer once a fortnight for the Buchblitz. This is an operation organised by narrator Peter Knox to support the librarian and ensure that the library can be effectively open for its regulation six minutes. Of course, it is the appearance of Connie the rabbit, a figure from Peter’s past, that gets this whole, bizarre plot rolling.

It is not very far into The Constant Rabbit that readers familiar with Jasper Fforde’s work will know, without doubt, they are in a Fforde novel. And it does not even take the appearance of a human-sized talking rabbit. No, it is the group of local English villagers, code-named for British prime ministers, for obscure reasons, who volunteer once a fortnight for the Buchblitz. This is an operation organised by narrator Peter Knox to support the librarian and ensure that the library can be effectively open for its regulation six minutes. Of course, it is the appearance of Connie the rabbit, a figure from Peter’s past, that gets this whole, bizarre plot rolling.

Jasper Fforde came to prominence with his intensely weird and wonderful Thursday Next series (starting with The Eyre Affair) that featured operatives who could jump in and out of the fictional world of novels, pet dodos, and plenty of toast. Since then he has moved into more pointed satire set in various alternative Britains. In Shades of Grey your social class was determined by your ability to see colour, and in Early Riser the world was characterised by the fact that most humans needed to hibernate for two months of the year and some shady dealings around a drug to help with this. So a world in which anthropomorphic animals are used to skewer British attitudes to ‘otherness’ should not come as a surprise to anyone familiar with his work.

In the world of The Constant Rabbit, the Anthropomorphic Event in the 1960s created a small group of human-like rabbits and, as the reader will learn as the book progresses, other species. Over 50 years later, rabbits being rabbits, their population has grown, but so has anti-rabbit sentiment. While rabbits are seen as a cheap labour force, they are constantly being harassed, particularly by a human action group called 2LegsGood (no prizes for picking the reference there) and have been mainly confined to specific colonies. The new party in power – the UK Anti Rabbit Party, or UKARP, run by a man called Nigel Smethwick (again, nothing subtle here), has plans to move all of the rabbit population to a massive walled enclosure in Wales. Anti-rabbit sentiment is virulent and widespread but also steeped in an aggressive form of Britishness:

The rabbit issue used to be friendly chat over tea and hobnobs in the old days, but the argument had, like many others in recent years, become polarised: if you weren’t rabidly against rabbits you were clearly only in favour of timidly bowing down to acquiesce to the Rabbit Way, then accepting Lago as your god and eating nothing but carrots and lettuce for the rest of your life.

The plot itself centres around Peter, who guiltily works for the organisation that tracks and arrests rabbits. Peter is one of the few people who can tell individual rabbits apart, so has been employed as a ‘spotter’, a job he keeps secret for fear of reprisals. But when Constance, a rabbit he knew at university, and her family come back into his life and move next door, things become more complicated for him and he has to determine where he stands:

Although I’d never consciously discriminated against rabbits… or considered myself leporiphobic in the least – I was. As a young man I’d laughed at and told anti-rabbit jokes and I never once challenged leporiphobic views when I heard them. And although I disapproved of encroaching anti-rabbit legislation I’d done nothing as their rights were slowly eroded.

Knox is a fairly typical Ffordian hero, an Arthur Dent-style British everyman who finds himself out of his depth but with reserves of strength to do what is right when called on. As Peter’s attraction to Constance grows and Peter’s daughter also becomes involved with rabbit activists, Peter finds himself having to pick a side. The whole builds to a final confrontation (the Battle of Mays Hill), which is foreshadowed early on in the narrative.

Putting the fairly standard plot aside, there is plenty to enjoy here. Fforde has always had a firm grasp of the absurd. Stories of other animals and their conversion in the Event, including a merino ram in Australia who survived a massacre and was memorialised by a giant statue in Goulburn (a real place). Peter’s surname itself (Knox) is used as a little Seuss-ian homage at one point. And then there is this throwaway line about London:

‘The way we see it, London is just one massive money-laundering scheme attached to an impressive public transport system and a few museums of which even the most honest has more stolen goods than a lock-up garage rented by a guy I know called Chalky.’

The parallels to current anti-immigrant sentiment in the UK (and elsewhere) are obvious, at times too obvious. Replace the word ‘rabbit’ with ‘Muslim’ or ‘Syrian’ or any other persecuted minority and the narrative almost works as well. At one point Fforde actually has some characters wondering whether the Anthropomorphic Event itself was deliberately satirical:

‘It’s further evidence of satire being the engine of the Event,’ said Connie, ‘although if that’s true, we’re not sure for whose benefit.’

‘Certainly not humans’,’ said Finke, ‘since satire is meant to highlight faults in a humorous way to achieve betterment and if anything the presence of rabbits has made humans worse.’

Even with this winking apology in the middle, some readers will find the analogy all too forced. Fforde is in fact using his satire to achieve betterment. And given where we are in the world at the moment, using satire to encourage readers who may not otherwise have done so to empathise with the oppressed and then to consider and confront their prejudices, is not a bad thing.

This review first appeared in Newtown Review of Books.

This and 500 more reviews can be found at www.pilebythebed.com.