As an economic recession hits Australia for the first time in 29 years Michael Janda* explains the difference between a recession and a depression.

In the Treasurer’s own words, this week’s June quarter economic growth figures were “devastating”.

In the Treasurer’s own words, this week’s June quarter economic growth figures were “devastating”.

Australia’s economy shrank seven per cent in just three months — that’s more than three times the next worst result on record (-2 per cent in 1974), and at least two years’ worth of good growth wiped out.

Most economists expect it will take until sometime in 2022 for the economy just to get back to where it was before the COVID-19 pandemic, others warn it might be 2023.

Given that, and forecasts that unemployment will peak at about 10 per cent by year’s end, many people are asking why we aren’t talking about a depression instead of a recession.

There’s a few reasons.

The Depression was really, REALLY, bad

The seven per cent quarterly fall may be the worst recorded in Australia, but those records from the Bureau of Statistics only go back to 1959.

For the year to June 2020, the Australian economy shrank 6.3 per cent, and economists generally think that’s about as bad as it will get, with most predicting a modest rebound in the current September quarter, despite Melbourne’s lockdown.

Compare that to the Great Depression.

Even though we don’t have directly comparable ABS figures, reliable estimates put the economic collapse at the beginning of the Depression in 1928-29 at 6.2 per cent — so pretty similar to what we’ve just seen.

But the economy fell a further 9.7 per cent in 1929-30 and, to rub salt into those wounds, another 2.1 per cent in 1930-31.

Economist Terry Rawnsley from SGS Economics and Planning said it was the three years of constant, severe economic decline that marked out the Depression as unique.

“In total, the Australian economy declined by 17.1 per cent during the three-year period,” he observed.

In a 2009 speech, the now head of the Australian Bureau of Statistics, David Gruen, made a similar observation comparing the Depression to the global financial crisis.

“What turned a recession in the 1930s into the Great Depression was the continued collapse in economic output for the subsequent two years, before recovery took hold in 1933.”

The continued falls in economic activity saw unemployment surge from 4.2 per cent to a peak of almost 20 per cent, and then remain above 11 per cent until the mid-1930s.

This high level of unemployment in turn meant fewer people with incomes to spend, which prolonged and deepened the downturn.

Unemployment didn’t drop back pre-Depression levels until the mass mobilisation for World War II.

Right now, unemployment is officially 7.5 per cent and expected to rise to about 10 per cent by year’s end.

The real rate of joblessness is probably above 11 per cent, and there is a lot of underemployment, but it is not as bad as during the Depression.

So, unless we have to endure second, third, fourth and fifth waves of COVID-19 without a vaccine or effective treatment, the current downturn looks likely to be a lot shorter and less severe than the Depression.

And, even if we end up experiencing an economic decline similar to the Depression, remember that we’re starting from a much higher base, with average incomes at the onset of the Great Depression around a fifth of what they are now, in real terms.

Governments weren’t much help in the Depression

Economic mismanagement played a key role in turning the stock market crash of 1929 and the recession that followed into the Great Depression.

“The classical economic approach involved reducing wages and trying to balance their budgets,” Terry Rawnsley explained.

“All of which just further reduced aggregate demand in the economy and worsened the Great Depression.”

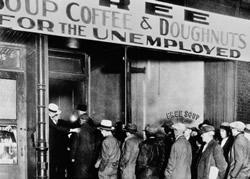

Not only did governments generally slash spending in response to their falling revenues and rising debts, they also didn’t provide even much basic support for the growing ranks of unemployed.

In his 2009 speech, Dr Gruen observed that Commonwealth unemployment and sickness benefits weren’t introduced until 1945.

“During the Great Depression, state governments had a support payment called ‘the susso’, short for sustenance payments,” he said.

“These varied by state but provided bare minimum support, with strict controls on what could be purchased with the coupons provided.”

They didn’t pay the rent, which saw many shanty towns and tent cities spring up around the country, and inspired this children’s ditty:

We’re on the susso now,

We can’t afford a cow,

We live in a tent,

We pay no rent,

We’re on the susso now.

The contrast with the modern response to severe economic downturns couldn’t be more stark.

In early 2009, the Rudd government announced a $42 billion stimulus package to help offset the effects of the global financial crisis — unlike most developed countries, Australia avoided recession.

That stimulus has already been dwarfed by the Morrison Government’s response to COVID-19, just as the initial economic downturn from the GFC has been dwarfed by the global coronavirus-induced recession.

In his July update to Parliament, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said the Government was providing “economic support for workers, households and businesses of around $289 billion”.

This week’s National Accounts show that record government subsidy payments of nearly $56 billion were made in the June quarter alone.

The combination of cash handouts and a coronavirus boost to welfare payments, along with an increased number of unemployed on JobSeeker, saw a stunning 41.6 per cent jump in social assistance benefits.

Despite a record 2.5 per cent drop in wages, the extra welfare payments meant the average disposable income rose 2.2 per cent.

The Depression was an economic crisis

Another big difference between the COVID recession and the Depression is implied by the former’s name.

While Australia’s economy wasn’t going great even before the pandemic hit — the 0.3 per cent slide in GDP in the March quarter pre-dated most of the lockdown effect and even got a boost from panic grocery buying — it wasn’t in crisis.

It’s possible Australia could have had a recession this year anyway, what with bushfires, very weak wages growth and persistently low business investment, but if we did it would have almost certainly been a small one.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything in March, shutting Australia’s borders to one of our biggest export earners — people — and closing down most of the services economy for weeks on end.

The 17.6 per cent plunge in household spending on services highlights the key driver of the economic slump.

There is still hope among many economists that as restrictions are gradually lifted — and especially if a vaccine or effective treatment is widely available — that economic growth will rebound quite strongly and the three-year long downward spiral of the 1930s will be avoided.

In contrast, the Depression lasted so long because it was a financial crisis, caused by fundamental problems in the system, such as too much debt and overvalued assets, and economic mismanagement made the work through of those problems much more painful and drawn out than it needed to be.

Debt the common factor

However, while this recession was triggered by a health crisis, there is a real risk it could morph into a financial one.

If that occurred it could see a short, sharp recession morph into a longer-term depression.

The main risk of this happening is one of the same factors that made the Great Depression so severe — debt.

Back in the 1920s, in the lead-up to the Depression, Australia’s problem was public debt.

“Total government gross debt was already well over 100 per cent of GDP before the onset of the Great Depression,” Dr Gruen explained.

“With fixed interest loans denominated in pounds sterling these levels increased to a peak of 205 per cent of GDP in 1931–32.”

The Government debt was so high that the UK’s banks — our main financiers at the time — didn’t want to lend us any more money, especially once the Depression hit. They wanted repayments instead.

“Australia lost access to the London capital market in 1929 because of high levels of government debt which severely constrained fiscal policy responses to the crisis.”

Basically, the Commonwealth and states couldn’t borrow more money to fund the kind of welfare, stimulus or public works programs we now know would have improved the economic situation (and, ironically, Australia’s ability to repay its debts).

That isn’t a problem now.

For one thing, Australia’s total public sector debt (Federal, state and local) going into the pandemic was estimated to be about 43 per cent of GDP.

It will rise sharply as a result of the pandemic spending, but may not even get to the levels Australia recorded before the Great Depression and it’s a lot lower than most other developed nations.

Also, this debt is now denominated in Australian dollars, not a foreign currency, meaning the nation literally cannot default on repayments as it could with its pound sterling debts in the 1930s.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the Government can just ask the Reserve Bank to print more money without end, but it does mean a lot more fiscal flexibility than Australia had in the 1930s.

However, while Australia doesn’t have a public debt problem, it does have a massive private debt issue.

At nearly 120 per cent of GDP, Australians’ household debts are second only to Switzerland.

The risk here is that, as Government income supports like JobKeeper and the JobSeeker coronavirus supplement wind down, and as bank mortgage repayment holidays also wrap up later this year and into early 2021, then a growing number of Australians might default on their loans.

That could put the banking system into trouble, which means they will need to call in loans, cut back on new lending and possibly start raising interest rates.

Space to play or pause, M to mute, left and right arrows to seek, up and down arrows for volume.

The Reserve Bank is conscious of this risk, which is one reason why it increased the amount of cheap funding it’s offering banks to around $200 billion, fixed for three years at 0.25 per cent (don’t you wish you could get mortgage rates that low!).

The Government can also use its relatively strong financial position to backstop the banks (as it did in the global financial crisis) or even to provide further assistance to homeowners or businesses in financial trouble.

There’s also a risk, openly acknowledged in Reserve Bank research, that the high debt levels Australians are carrying may make them more reluctant to spend money, which would be a big handbrake on recovery from the pandemic.

Again, the RBA is doing all it can to keep interest rates lower for longer, to put people’s minds at ease that they can still afford their repayments.

Also, the Federal Government can step in with more fiscal support through increased welfare payments, extending JobKeeper, spending more on infrastructure, hiring more people directly or cutting taxes to pump more money into the economy.

Depending how it pumps that money in and who gets it, some will be saved or invested and some will be spent.

So far, better economic management than the 1930s has kept the COVID recession from becoming a depression, but until there is a vaccine or cure for the virus the risk from any major policy missteps remains high.

*Michael Janda is the ABC’s senior digital business reporter, and has been covering business for ABC News Online since 2009. He can be contacted on Twitter @mikejanda.

This article first appeared at abc.net.au