The report also found Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are underrepresented in the midwifery profession due to the ongoing impact of racism, trauma and colonisation. Photo: NT Health.

Amid high rates of burnout, anxiety and stress, one in three Australian midwives is considering leaving the profession, meaning the nation’s crucial workforce is in crisis.

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) has published a report detailing 32 recommendations on how to save the sector, which already has a shortfall of midwives and students to meet future needs.

Commissioned by the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) and delivered by the Burnet Institute, the report found widespread staffing shortfalls, particularly in non-metropolitan areas, that would have a ”catastrophic impact” if the already high rates of workforce attrition increase above expectations.

Lead author of the Midwifery Futures project, Professor Caroline Homer AO, said urgent action was needed to boost midwifery student numbers by a fifth.

“Australian midwifery is in crisis,” Professor Homer said. “People in the sector already know this.

“We can’t keep doing the same thing and expect different results. This is the moment to do something differently.”

The report is the largest study of Australian midwives so far, taking in the views of more than 3000 midwives, 300 students and 70 educators as well as focus groups across the country.

Despite current modelling showing a slight excess in future workforce numbers to 2030, the report claims Australia is at risk of “a significant loss of workforce potential”. Among the midwives who completed the report’s survey, 46 per cent indicated they were currently considering leaving their job, and 36.6 per cent were considering leaving the profession.

Of most concern to the study’s authors was finding that 70.1 per cent of respondents were considering leaving for reasons other than retirement, with 68 per cent being under the age of 50.

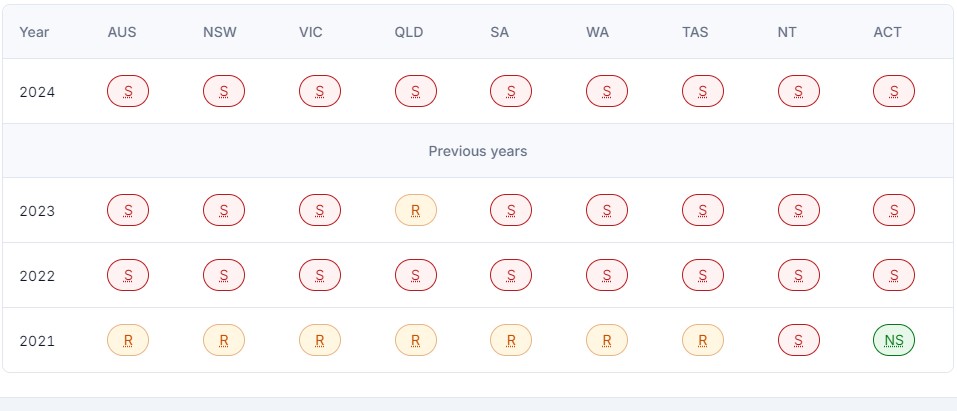

The latest occupation shortage list reveals the widespread scarcity of midwives across the nation. S = Shortage; R = Regional Shortage; NS = No Shortage. Image: JSA.

Not every midwife who indicates they are considering leaving the profession is expected to do so. The report cites studies that show actual leavers rates for health workers are far lower, with the average attrition rate for Australian midwives estimated to be 7 per cent between 2018 and 2023.

However, even if this rate climbs to 10 per cent, it would increase the annual workload per full-time equivalent (FTE) midwife by more than 50 per cent in all states and territories.

The report finds South Australia and the Northern Territory would be the most severely hit, with the effective workload increasing by 85 per cent.

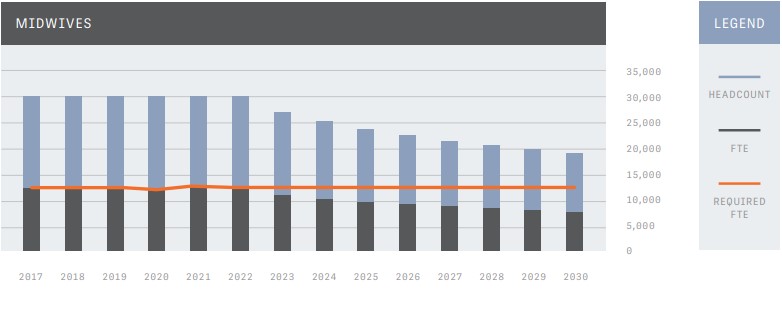

This graph from the report shows the effect of a 10 per cent leavers rate on midwife numbers between 2023 and 2030. Source: Ahpra.

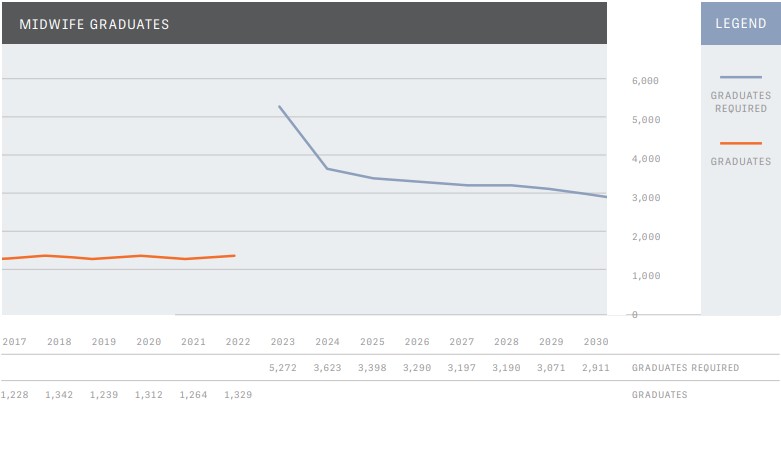

According to the report, mitigating this trend by 2030 would require all states and territories to produce graduates at twice the current levels.

The situation is most dire in Tasmania, where graduate numbers would need to increase threefold, albeit from a low base. However, the report finds this is particularly salient given the island state does not have any midwifery education programs.

This graph from the report shows how many midwife graduates are required to replace the 10 per cent leavers rate between 2023 and 2030. Source: Ahpra.

Recommendations made in the report broadly ask the state and federal governments to increase the visibility, governance and leadership of the profession; scale up models of care; and grow and support the midwifery workforce.

It declares they must increase the number of midwifery students as soon as possible, by at least 20 per cent – leading to about 1560 students graduating in the next two to four years. However, it also asks universities and health services to implement quarantined places for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander midwifery students so they can be appropriately supported in a sector that lacks First Nations representation.

Where there is a maternity service, the report asks leadership to be provided by midwives at government, employer, executive and clinical levels.

NMBA chair Adjunct Professor Veronica Casey AM said the board was pleased to have this report as a major step in long-term planning for the birth of future generations.

“With sustained commitment, investment and collaboration between Australian governments, employers, the higher education sector and professional bodies, we will be able to grow our midwifery workforce,” she said.