Reviewed by Rama Gaind.

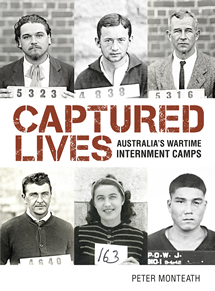

By Peter Monteath, NLA Publishing, $39.99.

Illustrated with some never-before-seen photographs and sketches, Captured Lives provides an insider’s look into life in the internment and prisoner-of-war camps that were spread across Australia during two world wars.

Illustrated with some never-before-seen photographs and sketches, Captured Lives provides an insider’s look into life in the internment and prisoner-of-war camps that were spread across Australia during two world wars.

Six faces stare at you on the cover. In the top left-hand corner is Anton Gueth, a German Buddhist monk, interned in Ceylon and sent to Australia during World War I. Top centre is Paul Dubotzki. On the top right hand side is Karl Moeller, the captain of a German ship captured during the Great War.

On the bottom left is Fritz Machotka; in the middle is the wife of an Italian fresco painter Maria Vagarini, who had been arrested and interned in Palestine before being sent, along with her husband, to Australia during World War II. At the bottom right is Hajime Toyoshima of Japan, whose aircraft was shot down over Darwin on 19 February 1942.

You will also learn the fascinating personal stories of such people as German-born Edmund Resch; Kurt Wiese, a prisoner of war for five years; and Reinhard Waldsax, a trained dentist.

The book covers over 30 of the main internment and prison-of-war camps that were spread across Australia during the war years. It includes more than 40 text boxes that focus on particular events and various civilian internees, prisoners of war, officials and others.

Historian Monteath provides a captivating visual look behind the barbed wire veil that was drawn around people deemed a threat to Australia’s security. Even if born in Australia, civilians from enemy nations were subjects of suspicion and locked away in internment camps.

Many were long-term residents of Australia, had contributed economically and brought new skills and know-how to the nation. For them, being interned was bewildering. What life was like as a prisoner of war is an eye-opener.

As the author says:

“It is about the experiences of combatants removed from the fields of battle and of civilians who were locked away in the interests of national security. It is about the actions taken by Australian authorities to detail ‘enemy aliens’, many of them Australian residents, many even ‘naturalised’ or ‘natural born’. And, in both words and images, it conveys the lived experiences of those who, like Churchill, found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, and paid a heavy price.”

The final paragraph of Monteath’s book in particular brings to mind current events, and can be seen as a caution:

“This absurdity of the detention of men like these, of condemning otherwise productive lives to unknown months and years of isolation and desolation, echoes through the history of Australia’s home front in the two world wars. More than that, it speaks to the twenty-first century and to the ever-present danger of allowing unfounded fears to stain the lives of prisoners and their captors alike.”