Nina Hendy* says questions are being asked about what banks and financial institutions are doing to protect their customers from financial losses.

Australians lost a combined $1.5 billion to investment scams last year, marking the highest financial losses of any other type of scam reported to authorities.

Australians lost a combined $1.5 billion to investment scams last year, marking the highest financial losses of any other type of scam reported to authorities.

So far this year, Australians have unwittingly handed over a whopping $115 million to an investment scam.

But as the losses continue to balloon, questions are being asked about what banks and financial institutions are doing to protect their customers from financial losses.

While pressure is being applied to banks at the moment, other financial institutions such as super funds need to be on the alert.

A surge in imposter bond scams last year prompted authorities to issue a public warning.

These usually impersonate real financial companies or banks and claim to offer government bonds or fixed term deposits.

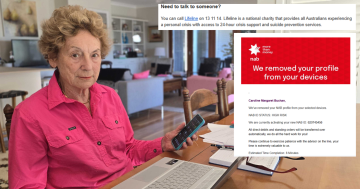

Text messages are an increasingly common contact method for scammers, Scamwatch data shows.

Promising big payouts and guaranteed returns, scammers utilise technology to ensure that investment scams appear to be legitimate opportunity.

Cyber experts like Professor of Cyber Security Practice at Edith Cowan University, Paul Haskell-Dowland is urging banks to step up and acknowledge their obligation to protect their customers with some basic checks and balances.

Victims often hastily make bank transfers to scammers in a bid to jump on board an opportunity too good to be true, he explains.

“Investment scam victims are often individuals who can’t afford to suffer a loss. Many of the reports I see is where people are losing all of their superannuation or all of their rainy day money.

“So convincing are these scams, that people invest everything they have into the scam, and continue to invest on the promise of greater returns or early returns,” Professor Haskell-Dowland says.

The fact that these scams are often linked to criminal activity and monies scammed from Australian victims is often moved overseas should prompt the banks realise they have a part to play in stamping out criminal activity, he says.

Lost to scams

Meanwhile, a damning report from the industry watchdog reveals that of more than $500 million lost to scams through the big four banks, only $21 million was reimbursed in compensation, the ACCC report found.

ACCC Deputy Chair Catriona Lowe is urging for a coordinated response across government, law enforcement and the private sector to combat scams more effectively.

The establishment of the Federal Government’s National Anti-Scam Centre forms part of that response.

Meanwhile, the Australian Banking Association is working on an industry-wide standard to implement consistency and improve scam victims’ experiences with their banks.

“Australians lose more money to scams than ever before in 2022, but the true cost of scams is much more than a dollar figure as they also cause emotional distress to victims, their families and businesses,” Lowe says.

But Professor Haskell-Dowland is adamant banks should be doing more.

Australia remains largely dependent on BSB and account numbers to undertake financial transactions.

Despite this, the banks are reluctant to implement greater safeguards for bank transfers, he says.

ISP tracing and linking BSB and account numbers to a name during the transfer process should be introduced as a starting point.

Automatically delaying larger transfers to unknown recipients until they can be verified is another option that the banks simply ignore, he says.

“Several transactions to a non-financial entity should surely raise a red flag and result in a block being put in place.

“There’s a lot more that can be done in this area and I’m surprised in the face of evidence, that this isn’t being shut down in a matter of days by the industry watchdog.

“It’s unacceptable that this is allowed to continue on,” Professor Haskell-Dowland says.

“Banks often hide behind the requirements being too technically difficult or the onus on privacy or that they can’t possibly do it, but when pressed on the technical challenges of being able to verify the receiver of the funds, they know it’s not that difficult.

“I would have some level of sympathy for them if this wasn’t 2023,” he says.

PayID and other security measures exist, but aren’t mandated, he adds.

“And of course, other banks in other countries manage it perfectly well,” he says.

Ongoing battle

The hesitation to do more stems from the ongoing battle to provide customers with instant financial transactions, and the banks are trying to win this race.

This means they’re reluctant to introduce security measures that impact the speed of transfers,” he says.

“If their customer is trading shares, betting on commodities or purchasing foreign transactions, a time delay may actually be a financial cost to their customers,” he says.

“The banks hide behind the fact that this is a user-initiated transaction from a customer who has decided to make the transfer from their account, so why should the bank hold that up? Banks aren’t typically in the job of saying no, so delaying transfers in this way would only be viable if it was legislated that this was required that the banks had to be more proactive in protecting their customers from this type of fraud,” he says.

Meanwhile, 17 Australian banks have joined a new Fraud Reporting Exchange platform designed to enable faster and more targeted communication in a fight against the scammers.

Owned and operated by an independent body built and funded by the banks, the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange is seen as a solution that the broader financial services sector will help fight against fraud and scams.

However, Haskell-Dowland says while it’s a step in the right direction, it’s once again not dealing with the problem in the right way.

“They’re still trying to detect the fraud after it has happened. This is still very much placing the onus on the customer to be cautious while providing them with no new tools to be better defended.”

Instead, the industry should be focusing on simple measures to ensure the customer knows exactly where they are sending the funds, such as recipient verification measures before funds are sent.

“This change is already happening in the UK and would give customers a clear indication of where the money is going.

“It may not be perfect, but if they think they are paying the bank and the name appears as ‘John Smith’, they can be assured that isn’t where the money is going,” he says.

“The banks still blame the customer if they choose to pay a rogue recipient, but at least they have a legitimate claim that the customer chose to make the payment in good faith,” he says.

If reluctance to implement this step continues, then making banks liable for losses may be the incentive needed to instigate change, he says.

While the banks have been responding with a range of education and awareness campaigns, these aren’t going to solve the scams crisis, Consumer Action Law Centre CEO Stephanie Tonkin says.

“What we need to see is the shifting of responsibility from vulnerable customers to the banks. They need to take more action to protect their customers.

“The Federal Government must intervene now and pass laws forcing banks to reimburse customers for scams losses, expect in circumstances of gross negligence,” Tonkin says.

*Nina Hendy is an Australian freelance business and finance journalist, regularly writing about personal finance, superannuation, building wealth, investing, saving, banking, financial markets, the economy and property.

This article first appeared at investmentmagazine.com.au