Simon Coghlan and Kobi Leins* say scientists have created the first ever living, programmable organism — raising many ethical questions.

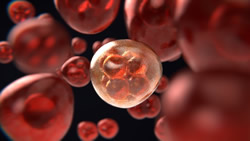

A remarkable combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and biology has produced the world’s first “living robots”.

A remarkable combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and biology has produced the world’s first “living robots”.

Last week, a research team of roboticists and scientists published their recipe for making a new lifeform called a xenobot from stem cells.

The term “xeno” comes from the frog cells (Xenopus laevis) used to make them.

One of the researchers described the creation as “neither a traditional robot nor a known species of animal”, but a “new class of artefact: a living, programmable organism”.

Xenobots are less than 1 mm long and made of 500–1,000 living cells.

They have various simple shapes, including some with squat “legs”.

They can propel themselves in linear or circular directions, join together to act collectively, and move small objects.

Using their own cellular energy, they can live up to 10 days.

While these “reconfigurable biomachines” could vastly improve human, animal, and environmental health, they raise legal and ethical concerns.

Strange new ‘creature’

To make xenobots, the research team used a supercomputer to test thousands of random designs of simple living things that could perform certain tasks.

The computer was programmed with an AI “evolutionary algorithm” to predict which organisms would likely display useful tasks, such as moving towards a target.

After the selection of the most promising designs, the scientists attempted to replicate the virtual models with frog skin or heart cells, which were manually joined using microsurgery tools.

The heart cells in these bespoke assemblies contract and relax, giving the organisms motion.

The creation of xenobots is groundbreaking.

Despite being described as “programmable living robots”, they are actually completely organic and made of living tissue.

The term “robot” has been used because xenobots can be configured into different forms and shapes, and “programmed” to target certain objects — which they then unwittingly seek.

They can also repair themselves after being damaged.

Possible applications

Xenobots may have great value.

Some speculate they could be used to clean our polluted oceans by collecting microplastics.

Similarly, they may be used to enter confined or dangerous areas to scavenge toxins or radioactive materials.

Xenobots designed with carefully shaped “pouches” might be able to carry drugs into human bodies.

Future versions may be built from a patient’s own cells to repair tissue or target cancers.

Being biodegradable, xenobots would have an edge on technologies made of plastic or metal.

Further development of biological “robots” could accelerate our understanding of living and robotic systems.

Life is incredibly complex, so manipulating living things could reveal some of life’s mysteries — and improve our use of AI.

Legal and ethical questions

Conversely, xenobots raise legal and ethical concerns.

In the same way they could help target cancers, they could also be used to hijack life functions for malevolent purposes.

Some argue artificially making living things is unnatural, hubristic, or involves “playing God”.

A more compelling concern is that of unintended or malicious use, as we have seen with technologies in fields including nuclear physics, chemistry, biology and AI.

For instance, xenobots might be used for hostile biological purposes prohibited under international law.

More advanced future xenobots, especially ones that live longer and reproduce, could potentially “malfunction” and go rogue, and out-compete other species.

For complex tasks, xenobots may need sensory and nervous systems, possibly resulting in their sentience.

A sentient programmed organism would raise additional ethical questions.

Last year, the revival of a disembodied pig brain elicited concerns about different species’ suffering.

Managing risks

The xenobot’s creators have rightly acknowledged the need for discussion around the ethics of their creation.

The 2018 scandal over using CRISPR (which allows the introduction of genes into an organism) may provide an instructive lesson here.

While the experiment’s goal was to reduce the susceptibility of twin baby girls to HIV-AIDS, associated risks caused ethical dismay.

The scientist in question is in prison.

When CRISPR became widely available, some experts called for a moratorium on heritable genome editing.

Others argued the benefits outweighed the risks.

While each new technology should be considered impartially and based on its merits, giving life to xenobots raises certain significant questions:

- Should xenobots have biological kill-switches in case they go rogue?

- Who should decide who can access and control them?

- What if “homemade” xenobots become possible? Should there be a moratorium until regulatory frameworks are established? How much regulation is required?

Lessons learned in the past from advances in other areas of science could help manage future risks, while reaping the possible benefits.

Long road here, long road ahead

The creation of xenobots had various biological and robotic precedents.

Genetic engineering has created genetically modified mice that become fluorescent in UV light.

Designer microbes can produce drugs and food ingredients that may eventually replace animal agriculture.

In 2012, scientists created an artificial jellyfish called a “medusoid” from rat cells.

Robotics is also flourishing.

Nanobots can monitor people’s blood sugar levels and may eventually be able to clear clogged arteries.

Robots can incorporate living matter, which we witnessed when engineers and biologists created a stingray robot powered by light-activated cells.

In the coming years, we are sure to see more creations like xenobots that evoke both wonder and due concern.

And when we do, it is important we remain both open-minded and critical.

* Dr Simon Coghlan is Senior Research Fellow in Digital Ethics, School of Computing and Information Systems, at the University of Melbourne. He tweets at @CoghSimon. Kobi Leins is a Senior Research Fellow in Digital Ethics in the School of Engineering at the University of Melbourne. She tweets at @kobotic.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com.