The wing of a Tu-95 explodes and drops to the ground as a drone hits. Photo: Screenshot.

It’s an increasingly common belief in military circles that ‘’drones are the weapon of the future’’. But as we have more than amply seen in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, that future is already here!

In scenes straight out of a technothriller or near-future conflict movie, Ukraine’s SBU (special forces) conducted a stunning attack against Russian air bases on 1 June, using more than 100 small first-person view (FPV) drones armed with explosives.

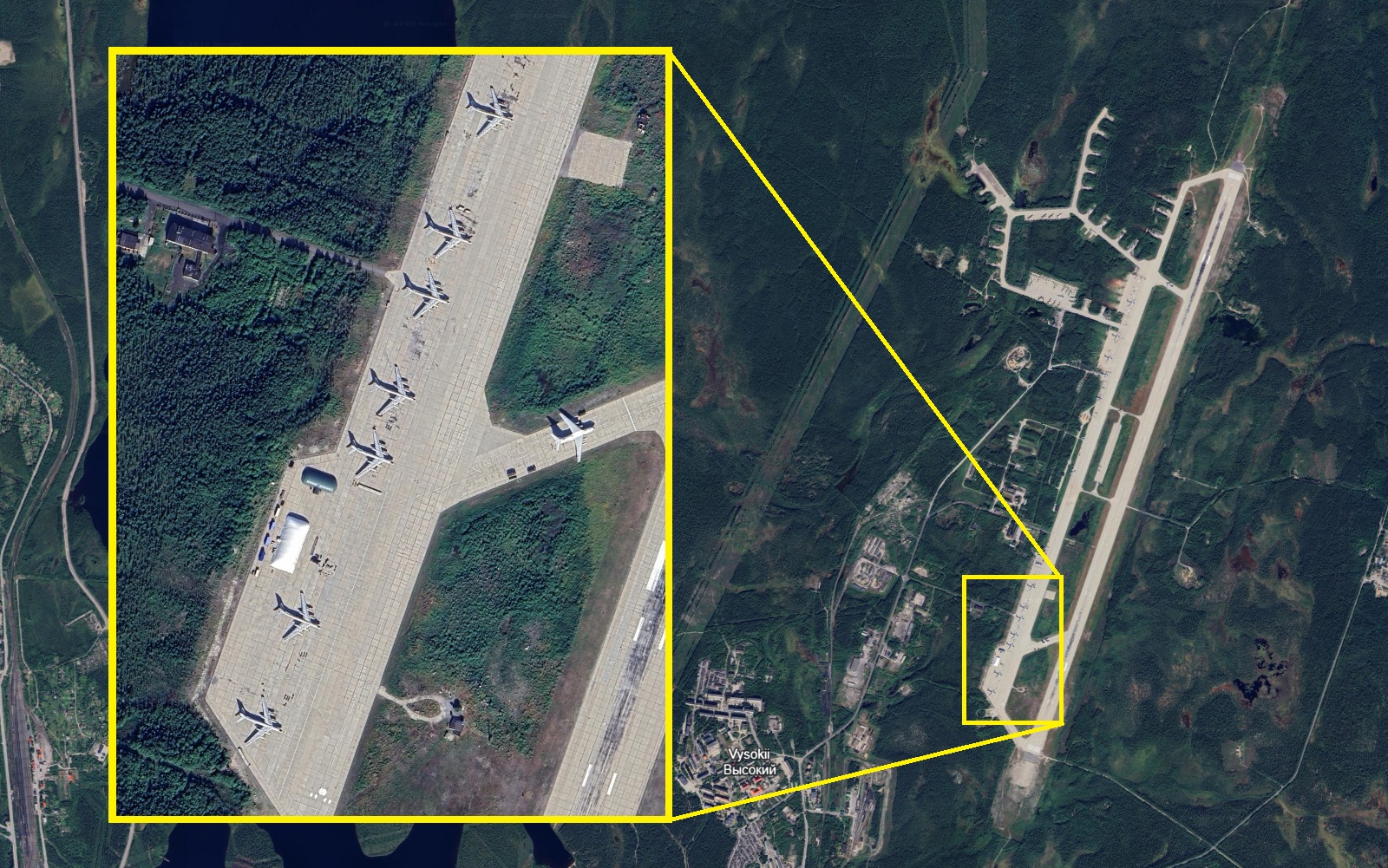

The attack reportedly targeted five air bases in Russia’s Arctic north, near Moscow, and in Siberia, and damaged or destroyed a number of Russian Tu-95, Tu-22M and Tu-160 strategic bombers, A-50 airborne command and control aircraft, and IL-76 transports.

The use of FPV drones has increasingly been seen in the war, with vehicles, buildings, helicopters and even personnel often subject to attack, often with devastating results.

But the uniqueness of the 1 June operation – dubbed ‘’Spiderweb’’ – is that some of the bases hit were more than 4000 km from Ukrainian soil.

Despite being based far from Ukrainian airspace, the bombers were rightly considered legitimate and key targets for the operation as they have repeatedly been used to launch cruise and ballistic missiles against Ukrainian cities throughout the war.

Spiderweb was reportedly 18 months in the planning, with the vehicles, explosives, and even the components of the drones themselves positioned inside Russia for several months before the attack. With only a range of a few kilometres themselves, it was necessary to preposition the drones close to the bases before they could be launched.

The drones used in the attacks were stored in the container roof cavities. Photo: Ukraine Government.

They were cleverly hidden in shallow roof cavities of truck-mounted containers, and were then transported by road thousands of kilometres to the bases, reportedly by Russian drivers who were unaware of their deadly cargo.

With the trucks parked near the bases on public roads or layovers, the drones were launched from hatches in the top of the containers, and appear to have flown across the bases to the rows of parked aircraft. The drones then appear to attack the aircraft with explosives at their weakest points near the planes’ wing roots, reportedly with the aid of AI-enabled software.

Once all the drones had been launched, the trucks self-destructed.

One of the drones used in the attack hovers above a Russian Air Force Tu-95 bomber shortly before pressing its attack. Photo: Screenshot.

Ukraine claims more than 40 aircraft were badly damaged or destroyed – almost one-third of Russia’s strategic bomber force – although Russia claims it lost 12 aircraft in the attack. But even if Ukraine’s number is inflated, the effect it will have on the free movement of vehicles inside Russia and the resources that country will need to redeploy to increase base security will only hamper its war effort.

The distance at which these short-range FPV drones were able to conduct this strike should be a wake-up call for the Australian Defence Force.

Australia has often relied on our remoteness from any potential adversaries as its best defence, with only intercontinental ballistic missiles or ship-launched cruise missiles able to reach targets in Australia. This was illustrated recently when Chinese warships conducted a circumnavigation of Australia, often closing to well within cruise missile range of some of our key bases and cities.

But Australia’s air and naval bases currently have no means by which to repel an asymmetric attack by small drones. As one former senior army leader recently noted, the notion that the distances in our region are a barrier that cannot be penetrated by autonomous systems is “dated and dangerous”.

“Numerous threats can be concealed in things like shipping containers that move through our region largely uninspected,” he said, adding that, while hardening facilities and rapidly evolving counter-drone capabilities is expensive, so are the capabilities these systems would be designed to protect.

Another observer wrote: “Here’s the uncomfortable truth: every major military installation in the world is vulnerable to this same style of attack right now … airbases, depots, critical logistics hubs – none of them would have fared any better. The tools are cheap, the tactics are public, and the threat is already global.”

Olyena Air Base in Russia’s far northern Murmansk region was hit. Before the attack, rows of Tu-95 bombers can be seen at the base. Photos: Google Earth.

The lessons for Australia are clear. Cheap, tactical drones can be used with strategic-level impact, AI and autonomous technologies are no longer future threats – they are here now, and defence planners must prepare for deep strikes from non-traditional or asymmetric platforms.

The ADF does have several counter-UAS projects underway, and some Australian companies such as Droneshield and EOS are considered world leaders in the development of laser and kinetic anti-drone systems and sell these overseas. But nothing is likely to be ready to be deployed locally within this decade.

Further, most of Australia’s bases have civilian roads running near their perimeters, with public carparks, service stations or other nearby amenities such as ports from which an attack such as that employed by Ukraine could be carried out.

It’s just another layer for the Federal Government and the ADF to consider when planning Australia’s future defence preparedness.