NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey has called the GST allocation system “absurd”, stating it would now be “virtually impossible” to return a surplus to the state’s budget next year. Photo: Daniel Mookhey/LinkedIn.

In response to the independent review of Australia’s system for distributing GST revenue, NSW Premier Chris Minns called out the Prime Minister to ask whether the $1.65 billion carve-up of his state was accidental or deliberate.

Each year the Commonwealth Grant Commission updates GST relativities to reflect developments influencing states’ fiscal capacities. To calculate this, it assesses each state’s ability to raise revenue and its costs in providing services.

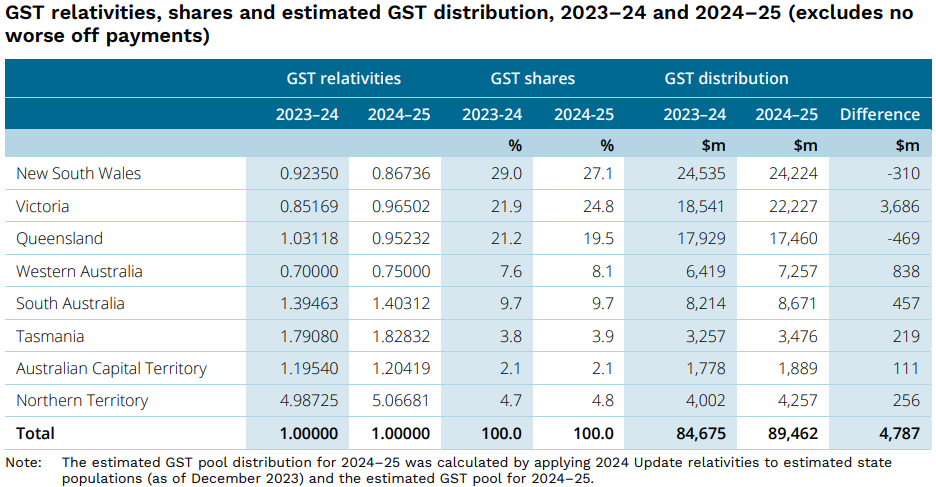

According to its March update, NSW will receive $310 million less in GST for the 2024-25 financial year compared with this one. Victoria will have an extra $3.7b in GST, while Western Australia’s portion is set to rise by $838m.

NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey told ABC Radio on Wednesday the equivalent of 14 cents out of every dollar paid by a NSW person in GST would be donated to other states, including those benefiting from high iron ore prices.

Premier Minns said on Wednesday: “This is a terrible set of circumstances for Australia’s largest state by any objective measure. I think the taxpayers of NSW need to understand why we’re currently in a situation where so much money has been withdrawn from Australia’s largest state and instead sent down to Victoria.

“I just want to make a really simple request to the Prime Minister and the Treasurer. Is this accidental or is it deliberate?”

At a doorstop on Thursday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was asked by journalists about his view on the matter. He said the commission was an independent process that had been in place for a long time, which the government did not plan to alter.

“It’s not something that my government has direct involvement in, or any other government,” he said. “Every year there is a debate about this, every year. This is not anything new.”

Other than NSW and Queensland, all states are set to receive an increase in their GST distribution and ”no worse-off” payments, with the NT gaining its largest ever in per capita terms ($995). The expected dip for those two states has been credited to growth in their relative revenue-raising capacities.

Meanwhile, Victoria’s increase was largely driven by its reduced capacity to raise mining revenue compared with other states, along with revisions of the 2021 Census showing growth in both its urban population and density.

Higher iron ore royalties have retained WA’s strong fiscal capacity. But growth in coal royalties has benefited other states, therefore reducing the estimate on its relative fiscal capacity for next year. Source: Grants Commission calculation. Image: Supplied.

Based on the operation of the GST relativity floor, WA received a $6.2b boost in distribution. The Coalition government was criticised in 2018 for introducing this floor, which changed the system by rejecting any GST payments falling beneath it.

These reforms benefited the wealthy mining state and the floor rose from 0.7 in 2023-24 to 0.75 in 2024-25. The Federal Government topping off the GST pool ($85b to $89b) and ”no worse-off” provision still requires them to spend $5.2b compensating other states over the next financial year.

More than 23 per cent of NSW revenue was contributed by GST this financial year, a significant portion of the budget it’s been expecting to decline – even before the review. Due to lower public spending amid high inflation and rising interest rates, its budget update in December expected it to fall by $1.85b until 2026-27.

Now the state’s share of the total GST pool will drop from 29 per cent to 27.1 per cent, an unexpectedly large knock to the budget of a region accounting for 31 per cent of Australia’s population.

Asked whether this was fair, Mr Albanese repeated his assertion that the commission was an independent body making decisions on an apolitical basis.

“For example, a territory like the Northern Territory has received more than its per capita share of the population, as have states such as Tasmania,” he said.

“I understand that state budgets are under pressure. That’s why we’ve increased health funding. That’s why we’re trying to reach agreements for increased education funding, for needs-based funding. That’s why we’re providing record funding for housing to every state and territory as well.”