Lisa Earle McLeod* says when something terrible happens to a neighbour or co-worker, the last thing you should do is avoid them because you ‘don’t want to intrude’.

“We don’t want to make things worse.”

“We don’t want to make things worse.”

When my neighbour’s high school-age daughter died of cancer, it was horrible.

No one knew what to say or do. A group of us decided to take food over before the funeral, but everyone was afraid to be the person who dropped it off.

The common refrain was: “I don’t want to intrude.”

The truth was, people were afraid.

One neighbour said: “I’m not good at things like this; I’m afraid I’ll say the wrong thing and make them feel worse.”

Therein lies the problem. People are so afraid of making a mistake that they avoid the situation entirely.

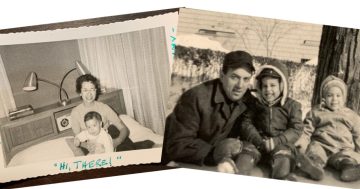

I have a sad, dark history with this particular scenario.

My younger brother died suddenly of meningitis when I was in high school.

After it happened, most of the other students avoided me.

In hindsight, I understand it was due to their own discomfort, but at the time, I felt like a tragic figure hovering on the outside of my community.

In my neighbours’ case, their daughter was sick for months.

Her cancer took a turn for the worse, and she died in the spring of her junior year in high school.

Everyone had followed the story, and was heartsick at the tragic end.

Yet people were still reluctant to go see the family.

As I listened to my neighbours discussing their discomfort, I felt myself going right back to high school.

As someone who has been on the grieving side of this, I told them: “I can promise you, if someone loses a child, nothing you say in that situation is going to make it worse.

“Their child is dead; the only thing that makes it worse is when people avoid you.”

If your friend, neighbour, employee, boss, or co-worker has a death in the family, it’s hard to know what to say.

You don’t want to make someone burst into tears, you don’t want to cause a scene, or appear nosy.

It’s tough, but here’s the deal: If we’re honest, the thing that makes us most afraid is the idea that we might have to get up close and personal with someone else’s raw grief.

I’ll always remember the one girl who, on my first day back in school after my brother died, walked right up, looked me in the eye, and said this:

“I am so sorry about the loss of your brother. My family and I have been thinking about your family.

“If you need anything today, come find me and I’ll help you.”

I felt a sense of relief. Everyone knew, I’d seen them huddled in the cafeteria talking about it all morning.

When that one 16-year-old girl had the emotional courage and maturity to approach me, and acknowledge my loss, I felt almost human for the first time in days.

When you take the leap, and speak directly into the loss, there’s a risk they may burst into tears.

They might totally lose it and fall to their knees in grief.

That’s the reason you need to do it.

When people are grieving, they need to be seen. They need a witness for their sorrow. They need to know they’re not alone.

Next time something horrible happens, be the person who has the courage to walk into the grief.

Straighten your back, walk over to their house or office, knock on the door, and say: ‘I’m here for you’.

* Lisa Earle McLeod is best known for creating the popular business concept ‘Noble Purpose’. She is the author of Selling with Noble Purpose and Leading with Noble Purpose and can be contacted at mcleodandmore.com.

This article first appeared on Lisa’s blogsite