Christopher J. Ferguson* says there are several common myths about the effects of ‘technology addiction’ that deserve to be debunked by actual research.

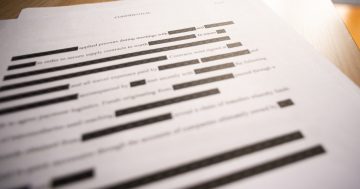

Photo: Kelly Sikkema

How concerned should people be about the psychological effects of screen time?

Balancing technology use with other aspects of daily life seems reasonable, but there is a lot of conflicting advice about where that balance should be.

Much of the discussion is framed around fighting “addiction” to technology.

But to me, that resembles a moral panic, giving voice to scary claims based on weak data.

For example, in April, US television journalist Katie Couric’s America Inside Out program focused on the effects of technology on people’s brains.

The episode featured the co-founder of a business treating technology addiction.

That person compared addiction to technology with addictions to cocaine and other drugs.

The show also implied that technology use could lead to Alzheimer’s disease-like memory loss.

Others, such as psychologist Jean Twenge, have linked smartphones with teen suicide.

I am a psychologist who has worked with teens and families and conducted research on technology use, video games and addiction.

I believe most of these fear-mongering claims about technology are rubbish.

There are several common myths of technology addiction that deserve to be debunked by actual research.

Technology is not a drug

Some people have claimed that technology use activates the same pleasure centres of the brain as cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine.

That’s vaguely true, but brain responses to pleasurable experiences are not reserved only for unhealthy things.

Anything fun results in an increased dopamine release in the “pleasure circuits” of the brain — whether it’s going for a swim, reading a good book, having a good conversation, eating or having sex.

Technology use causes dopamine release similar to other normal, fun activities: about 50 to 100 per cent above normal levels.

Cocaine, by contrast, increases dopamine 350 per cent, and methamphetamine a whopping 1,200 per cent.

In addition, recent evidence has found significant differences in how dopamine receptors work among people whose computer use has caused problems in their daily lives, compared with substance abusers.

But people who claim brain responses to video games and drugs are similar are trying to liken the drip of a tap to a waterfall.

Comparisons between technology addictions and substance abuse are also often based on brain imaging studies, which are themselves sometimes unreliable at documenting what their authors claim.

Other recent imaging studies have also disproved past claims that violent games desensitised young brains, leading children to show less emotional connection with others’ suffering.

Technology addiction is not common

People who talk about tech addictions often express frustration with their smartphone use why kids game so much.

But these aren’t real addictions, involving significant interference with other life activities such as school, work or social relationships.

My own research has suggested that 3 per cent of gamers — or less — develop problem behaviours.

Most of those difficulties are mild and go away on their own over time.

Technology addiction is not a mental illness

At the moment, there are no official mental health diagnoses related to technology addiction.

This could change: the World Health Organisation (WHO) has announced plans to include “gaming disorder” in the next version of its International Compendium of Diseases.

But it’s a controversial suggestion.

I am among 28 scholars who wrote to the WHO protesting that decision.

The WHO seemed to ignore research that suggested “gaming disorder” is more a symptom of other, underlying mental health issues such as depression, rather than its own disorder.

This year, the Media Psychology and Technology division of the American Psychological Association, of which I am a fellow, likewise released a statement critical of the WHO’s decision.

Controversies aside, I have found that current data doesn’t support technology addictions as stand-alone diagnoses.

For example, there’s the Oxford study that found people who rate higher in what is called “game addiction” don’t show more psychological or health problems than others.

Additional research has suggested that any problems technology overusers may experience tend to be milder than would happen with a mental illness, and usually go away on their own without treatment.

‘Tech addiction’ is not caused by technology

Most of the discussion of technology addictions suggest that technology itself is mesmerising, harming normal brains.

But my research suggests that technology addictions generally are symptoms of other, underlying disorders like depression, anxiety and attention problems.

People don’t think that depressed people who sleep all day have a “bed addiction”.

This is of particular concern when considering who needs treatment, and for what conditions.

Efforts to treat “technology addiction” may do little more than treat a symptom, leaving the real problem intact.

Technology is not uniquely addictive

There’s little question that some people overdo a wide range of activities.

Those activities include technology use, but also exercise, eating, sex, work, religion and shopping.

But few of these have official diagnoses.

There’s little evidence that technology is more likely to be overused than a wide range of other enjoyable activities.

Technology use does not lead to suicide

Some pundits have pointed to a recent rise in suicide rates among teen girls as evidence for tech problems.

But suicide rates increased for almost all age groups, particularly middle-aged adults, for the 17-year period from 1999 to 2016.

This rise apparently began around 2008, during the financial collapse, and has become more pronounced since then.

That undercuts the claim that screens are causing suicides in teens, as does the fact that suicide rates are far higher among middle-aged adults than youth.

There appears to be a larger issue going on in society.

Technopanics could be distracting regular people and health officials from identifying and treating it.

One recent paper linked screen use to teen depression and suicide.

But another scholar with access to the same data revealed the effect was no larger than the link between eating potatoes and suicide.

This is a problem: scholars sometimes make scary claims based on tiny data that are often statistical blips, not real effects.

To be sure, there are real problems related to technology, such as privacy issues.

And people should balance technology use with other aspects of their lives.

It’s also worth keeping an eye out for the very small percentage of individuals who do overuse.

There’s a tiny kernel of truth to our concerns about technology addictions, but the available evidence suggests that claims of a crisis, or comparisons to substance abuse, are entirely unwarranted.

* Christopher J. Ferguson is Professor of Psychology at Stetson University in Orlando, Florida. He tweets at @CJFerguson1111.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com.