Participation in the 2024 survey is anonymous, voluntary and closes on 27 November. Photo: ICAC SA.

The Independent Commission Against Corruption SA (ICAC SA) is calling on South Australian public officers to participate in its next integrity survey, a month after its head resigned early from the embattled agency.

All public officers working in state and local government agencies have been invited to participate in the 2024 Public Integrity Survey. ICAC SA will use the responses to identify integrity risks and vulnerabilities, plus work with public agencies to keep out corruption.

This survey hasn’t been run since 2021 – the same year controversial amendments were implemented into the legislation governing public integrity in SA.

Outgoing corruption commissioner, Ann Vanstone, was a stern critic of the changes and tabled six reports exploring such issues in the fortnight before leaving what she labelled “the weakest integrity agency in Australia”.

The former Supreme Court Justice made her exit from ICAC SA on 6 September – after serving only four years of her seven-year term.

In early July, Ms Vanstone told the public her resignation was prompted by “a number of factors, some personal, but most professional”.

“The 2021 amendments to the legislation governing public integrity in South Australia damaged the scheme, under the guise of making it more ‘effective and efficient’,” she said.

“On multiple occasions, I have pointed out the significant problems within the scheme to this government and the last, and to the parliamentary committee that oversees us. But I have run out of steam.

“I have not asked for the previous scheme to be restored. I have recommended modest reform and an independent review of the amendments to see how effective they are. My words have fallen on deaf ears.”

“I hope the next commissioner will succeed where I have failed,” said outgoing corruption head Ann Vanstone. Photo: ABC Radio Adelaide.

Prior to leaving she said the agency’s chief concern had been in “finding a way to make an impaired system work” since the changes in 2021.

“In essence, the public interest is not served by narrowing the definition of corruption, or by isolating the commission from the intelligence sources constituted by all complaints and reports, or by completely divorcing us from the prosecution process so that we are unable to assist a prosecution,” said Ms Vanstone.

“Absurdly, we are not even allowed to speak to the prosecutor, meaning they are denied access to the expertise and knowledge of commission investigators who best know the matter. It makes the commission the only integrity and anti-corruption agency in Australia to be precluded from directly briefing the prosecuting authority.

“Likewise, the public interest is not served by gagging us to ensure we cannot comprehensively share with the community what we know about integrity issues in South Australian public administration; and of course, it is not served when the public is required to pay the legal fees of those convicted of an offence, simply because they were investigated by the commission.”

When the last public integrity survey was held in 2021, then-commissioner Ann Vanstone wrote frankly about her concerns in the report’s foreword.

“The survey was distributed in the last months of 2021, soon after significant amendments to the Independent Commissioner Against Corruption Act 2012, which narrowed the commission’s jurisdiction,” she wrote.

“Participants were not asked for their views of the amendments. Yet many public officers provided unsolicited comments expressing an apprehension that the changes had eroded the commission’s independence.”

More than 7000 responses were provided to the survey from public officers across SA, which then-commissioner Vanstone published two reports on their findings.

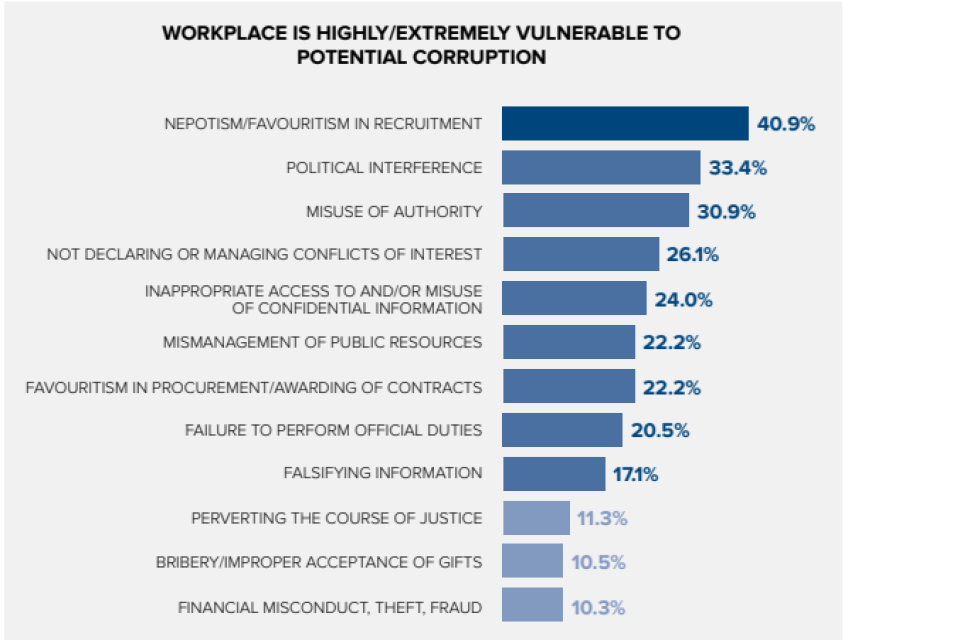

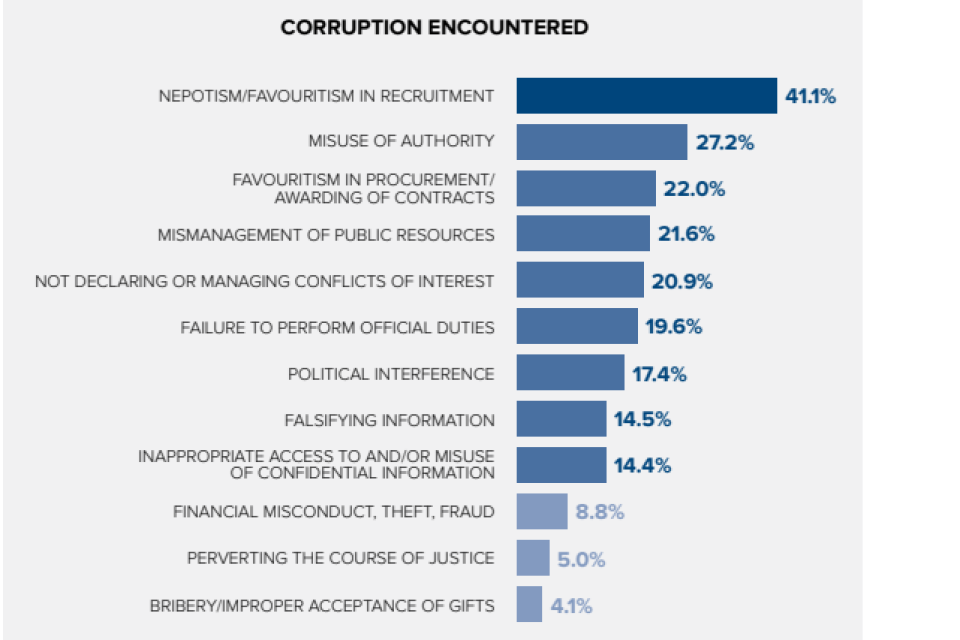

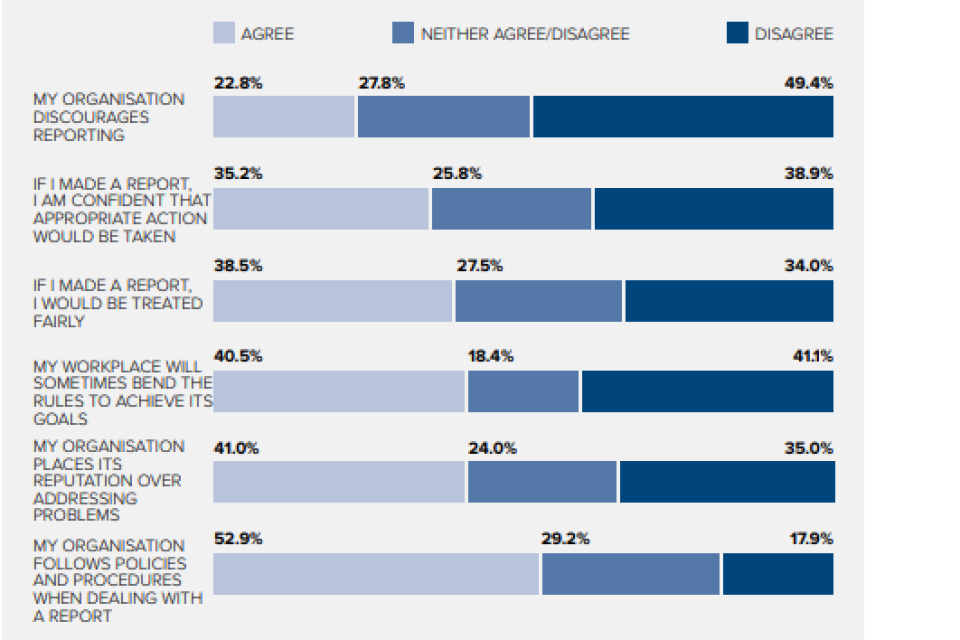

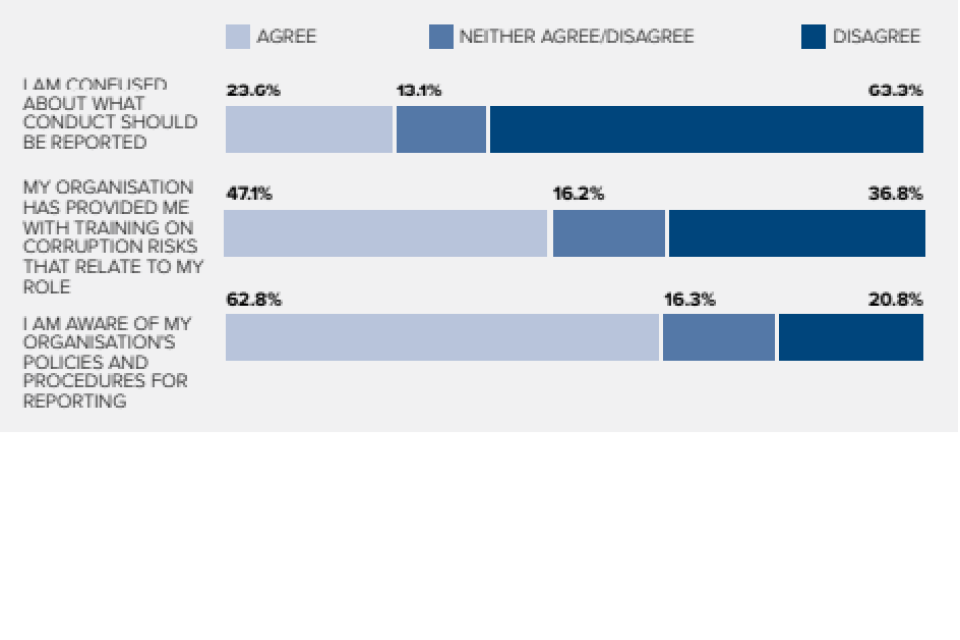

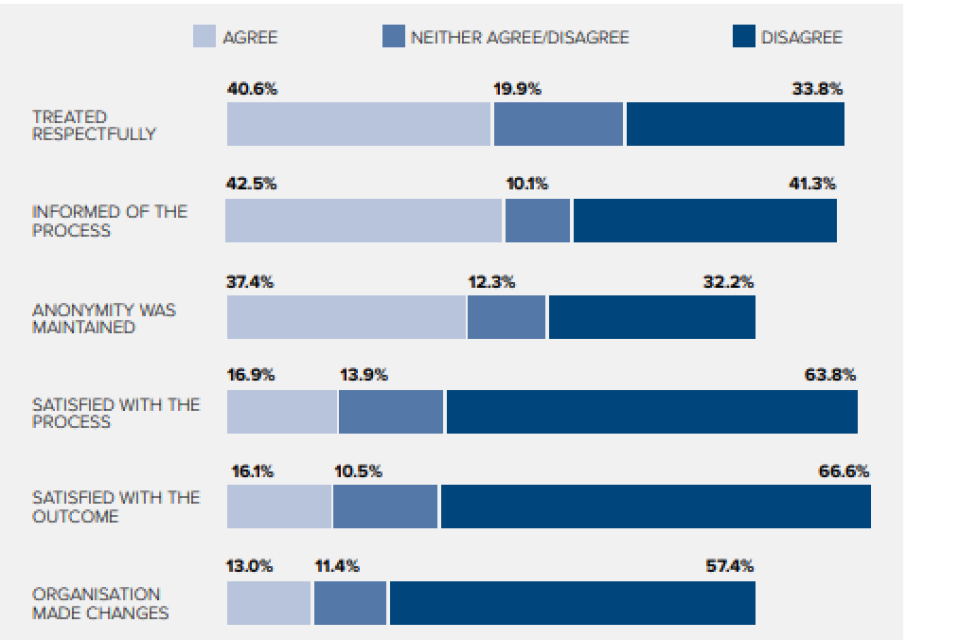

“The majority of participants believe their workplace to be vulnerable to corruption, and many indicated that they had personally encountered corruption,” she wrote. “However, not all participants felt safe to report what they saw.

“Many participants were fearful of negative repercussions should they report, including losing their job. Participants want to be able to report anonymously; protections for whistle-blowers were seen to be ineffective.”

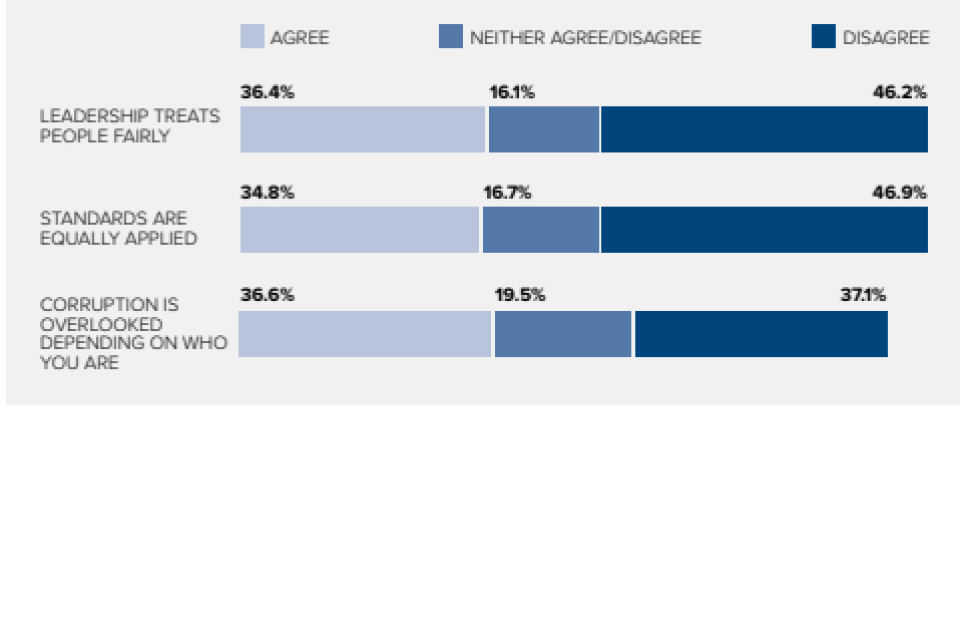

According to Ms Vanstone there was a real danger in finding many participants had expressed the view that preferential treatment was commonplace in their workplace, and that corruption might be overlooked depending on who was involved.

“The survey shows a significant disparity between the perceptions of senior leaders and other participants,” she wrote. “Most senior leaders perceived their workplaces to have very little vulnerability to corruption and felt empowered to report it.”

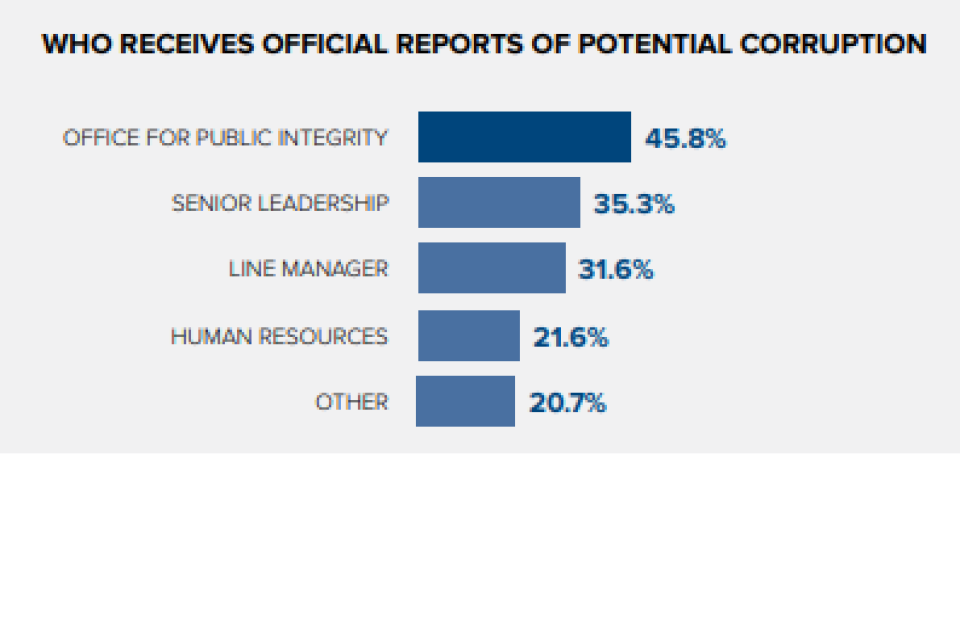

Reports on the 2024 survey findings will be published on the commission’s website in the first half of 2025. Participants have been told that any information provided in their survey response does not constitute a report of suspected corruption, which should be directed to the Office for Public Integrity.