Economists may not be big fans of negative gearing, but someone’s going to be putting money into housing. Illustration: Sorbetto.

As we deal with a cost-of-living crisis™ and a housing crisis™, it’s a fool’s errand to try to garner sympathy for landlords. But what the hell, eh?

From what some commentators write, you’d think negative gearing was a new creation designed to keep people out of the property market. An invention, perhaps, of the greedy baby boomers.

In fact, it was designed to encourage investment. That was the goal when it was put on the books in 1936.

And indeed, it has brought investors into the market and those investors rent their properties (if they don’t, the system doesn’t work).

In case you’re wondering, according to the ATO: “A rental property is negatively geared if it is purchased with the assistance of borrowed funds and the net rental income, after deducting other expenses, is less than the interest on the borrowings”.

Those expenses are important because they include rates and land tax and they’re not cheap. In fact, the maths of real estate is fairly brutal.

Let’s say you have a three-bedroom, one-bathroom rental in Wanniassa going for $630 a week (about $33,000 a year). The land tax on that is about $100 a week. Rates are about $60 a week. That $630 a week rent is now $470. On an asset that might be worth $700,000, your return is a truly atrocious 3.49 per cent (and we haven’t even bought insurance yet).

Maybe it’s the government being greedy, not the landlord.

The design of negative gearing actually encourages lower rents because if the difference between the interest and the rent can’t be claimed as a loss, the landlord has some choices: they can either absorb the loss (but remember, all landlords are bastards, so what are the chances they’d do that?), they can put up the rent to cover the cost (because all landlords are bastards) or a combination of the two options (if they’re 50/50 on the whole bastard thing).

Oh, there’s a fourth option: they can leave the market.

Perhaps the property will be bought by an owner-occupier, in which case it will no longer be a rental, or maybe someone who doesn’t need the tax loss will buy it. That’s a problem for renters. A landlord without negative gearing can set rent at whatever price the market can bear and they have no incentive to lower rents because they aren’t chasing a tax deduction.

(It should also be noted that negative gearing would not be as attractive to PAYG earners if the marginal tax rates weren’t so high, but let’s beat our heads against that wall another day.)

It might be unfashionable to make the case, but the simple reality is that renters need landlords and landlords need negative gearing.

At this point in any article about negative gearing, the law dictates that you reference the period from 1985 to 1987 when the Hawke Government abolished negative gearing. What happened then? Well, as with all things, it’s complicated, as this ABC Fact Check attests. It gets worse when you try to draw conclusions to wicked problems with just one data point, but that’s all we’ve got. There was an interesting observation, though.

During the period that negative gearing was abolished, real rents increased only in Sydney and Perth. Why? Because that’s where rental vacancies were extremely low. At that time, Sydney’s vacancy rate was one per cent and Perth’s was 1.4 per cent.

Oh. That’s not good.

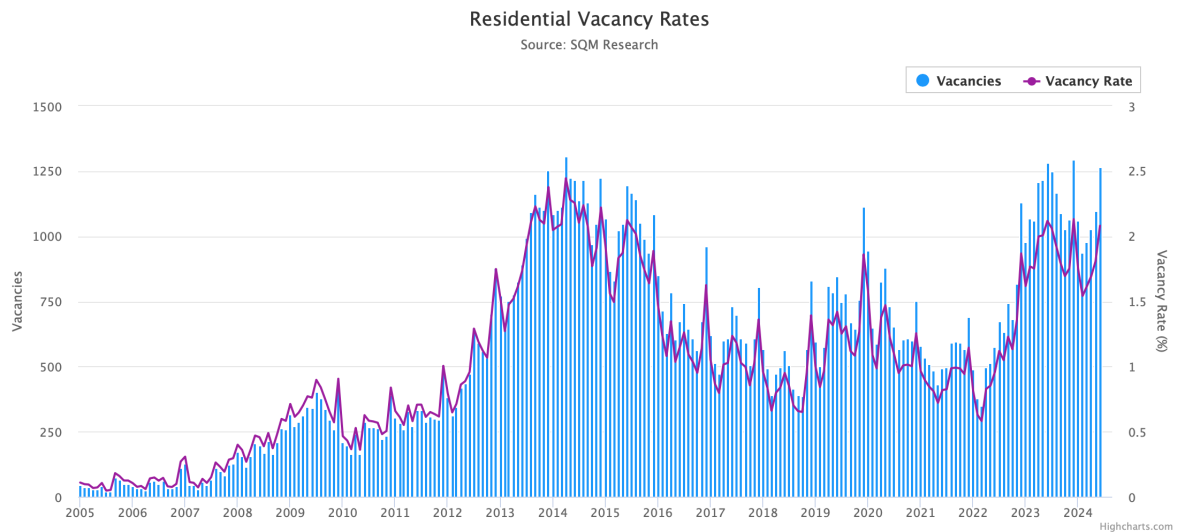

In the ACT at the moment, the vacancy rate is a nation-leading 2.4 per cent but has regularly been well below one per cent. The picture is much worse across the country.

According to SQM Research, in June 2024, Sydney’s vacancy rate was 1.7 per cent; Brisbane, 1.1 per cent; Adelaide, 0.7 per cent; Hobart, 1.5 per cent; Melbourne, 1.5 per cent; Perth, 1.5 per cent; Darwin, 0.9 per cent; giving us a national figure of 1.3 per cent.

ACT residential vacancy rates. Table: SQM Research.

In other words, the tight market that helped push up rents in the 80s when negative gearing was abolished is here now, right across the country.

Even if a government had the courage to roll the dice on negative gearing, it is estimated there are around 2.24 million taxpayers in Australia who are property investors, and collectively they own 3.25 million investment properties. That’s a lot of property owners to irritate – and it might also give the irrits to their tenants if rents then rise.

Negative gearing isn’t the be-all and end-all of property investment, but it is a sweetener in an asset class that returns in the low single digits.

Economists and policy purists may not like negative gearing but, if you’re a taxpayer, you should be wary of those who want to abolish it, because if private landlords aren’t renting to tenants, those tenants will look to government for a roof, which means you’ll be footing the bill and it’s sure to cost more than the one we currently get.

Original Article published by David Murtagh on Riotact.