Jonathan Amos* says marine biologists are surprised and delighted at the variety of sea creatures which have made their home on Shackleton’s lost ship.

While the world gaped at the extraordinary preservation of Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, one group of people were agog at something else in the crystal-clear underwater footage.

While the world gaped at the extraordinary preservation of Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, one group of people were agog at something else in the crystal-clear underwater footage.

They were polar biologists, searching for the different creatures around the wreck.

There were the expected invertebrates — filter-feeders such as sea anemones and sea lilies — but some surprises, too.

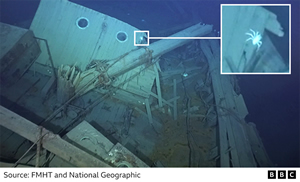

The star, undoubtedly, was the squat lobster seen climbing over the wreck (in picture).

It was scuttling past a porthole on the famous wooden ship which sank to the bottom of the Weddell Sea in 1915 after being crushed by sea ice.

Squat lobsters aren’t really lobsters at all, being more closely related to some species of crabs.

Huw Griffiths, from the British Antarctic Survey, said it was hard to be sure given the resolution of the released imagery, but the animal could be from the Munidopsis genus.

Dr Griffiths, who was not on the expedition to find the Endurance, said Munidopsis was a genus of squat lobster with more than 200 known species.

“Its members are mainly found on continental slopes and on abyssal plains. One record of a species, M. albatrossae, was found in 2006 in the Bellingshausen Sea on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula,” Dr Griffiths said.

“However, this is a first for the Weddell Sea, if you discount fossils found on Seymour Island further to the north.”

Confirmation will require further analysis of the much higher resolution imagery gathered by the Endurance22 project.

Its submersibles were equipped with 4K cameras that swept back and forth across the wreck to make a detailed photogrammetric record.

That there are so many filter-feeders covering the wreck is no surprise.

These animals will colonise anything that stands out on the ocean floor, which in this region of the Weddell Sea would include boulders dropped by passing icebergs.

Getting even just a few centimetres above the sediment gives greater opportunity to catch particles of food in the bottom currents.

Creatures such as sea squirts will pump water in-and-out through their two syphons to collect plankton and ‘marine snow’, essentially dead things and faeces that rain down from the sea surface.

One organism in the new pictures of the Endurance really catches the eye. It’s a yellow crinoid or sea lily, an animal not a plant.

It was seen anchored just under the hand rail, on the stern of the ship.

There was also an interesting fan-like structure near the ship’s wheel that Marine Biologist at Essex University, Michelle Taylor believes to be a hydroid.

“Hydroids are colonial animals that live in little box-like high rises together,” Dr Taylor said.

“They are the fine, slightly stingy, fur that you find covering the bottom of boats. Look for anything with very fine hairs and that’s probably a hydroid.”

It was widely anticipated that the Endurance would be in a decent state of preservation as the types of worms that routinely devour wooden structures at higher latitudes are not present in the waters around the White Continent.

This in part is because of the absence of a source of wood going into the ocean in that region. There are no forests on Antarctica and there haven’t been for millions of years.

Organisms adapted to such nourishment would therefore have slim pickings.

Marine Zoologist at Portsmouth University, Simon Cragg says the Antarctic Circumpolar Current that moves around the White Continent also works to keep wood borers from moving closer to the polar south.

“Shipworms have been the bane of wooden ships throughout history and determined ship design from the classical Greek period through to Nelson’s time and even today,” Professor Cragg said.

“Decay of wood by marine bacteria and marine fungi is very slow, especially at low temperatures.”

Marine biologists have had only the briefest of glimpses of what’s living on Shackleton’s ship. The Endurance22 project initially released just a 90-second sequence of video.

When longer views become available, who knows what else will be revealed to have taken up residence?

“There are plenty of mysteries left to solve,” Dr Griffiths said.

*Jonathan Amos has been a science correspondent with the BBC since 1994. His online reporting focuses on the Earth sciences, with a particular interest in the changes taking place in polar regions.

This article first appeared on the BBC Science website.