Tom McKay* explains how police are tapping into Google’s massive mobile device location tracking database to hunt down suspects.

Law enforcement queries of Google’s massive mobile device location tracking database, which employees call Sensorvault, have “risen sharply in the past six months,” The New York Times reported recently, citing sources at the company.

Law enforcement queries of Google’s massive mobile device location tracking database, which employees call Sensorvault, have “risen sharply in the past six months,” The New York Times reported recently, citing sources at the company.

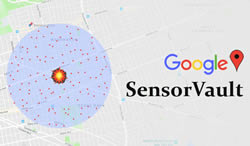

It’s not clear how often police ask Google to produce results from the database, which can be used to narrow down which devices were in a specified geographic location at a certain time (mostly phones running its Android OS, but also some on Apple’s iOS).

The technique can be used to generate leads.

But critics say it resembles a fishing expedition that raises Constitutional questions under the US Fourth Amendment, which restricts the scope of warrants and mandates authorities show probable cause to search. The Times wrote: “The practice was first used by Federal agents in 2016, according to Google employees, and first publicly reported last year in North Carolina.”

“It has since spread to local departments across the country, including in California, Florida, Minnesota and Washington.”

“This year, one Google employee said, the company received as many as 180 requests in one week.”

“Google declined to confirm precise numbers.”

“The technique illustrates a phenomenon privacy advocates have long referred to as the ‘if you build it, they will come’ principle — anytime a technology company creates a system that could be used in surveillance, law enforcement inevitably comes knocking.”

“Sensorvault, according to Google employees, includes detailed location records involving at least hundreds of millions of devices worldwide and dating back nearly a decade.”

Last year, the US Supreme Court ruled that authorities must obtain a search warrant and show probable cause to obtain location records from third parties like Google, although Google had already decided that it would demand warrants to hand over the data.

Since each “geofence warrant” — varying from tiny spaces to larger areas covering multiple blocks, and over similarly variable periods of time — can potentially rope in tens to hundreds of devices owned by many people, the company first provides records without attaching names or other identifying information to investigators.

Once authorities narrow down the number of leads, such as by identifying patterns of movement that indicate potential involvement in a crime or potential witnesses that were in the area, they can request further location data or ask Google to reveal “the name, email address and other data associated with the device,” The Timeswrote.

However, some jurisdictions can require a second warrant before identifying information is handed over.

As The Times separately reported, Location History is not enabled by default and has to be activated when opting in to certain services.

Its primary purpose for Google, however, is targeted advertising and services like determining when stores are busy.

Even if Location History is turned off, other Google apps collect some location data as part of Web & App Activity settings (though this data is kept in a separate Google database).

While the warrants have solved crimes, they can also result in authorities nabbing the wrong person.

For example, The Times explained the case of Phoenix man Jorge Molina, who was arrested after police said his phone was detected in the vicinity of a drive-by shooting and then realised his vehicle resembled one at the crime scene picked up by security video.

Molina spent a week in jail before friends produced texts and Uber receipts backing up an alibi, while police later arrested Marcos Gaeta, “his mother’s ex-boyfriend, who had sometimes used Mr Molina’s car” and had a “lengthy criminal record.”

Molina’s public defender, Jack Litwak told the paper he believed it was possible that Google’s records were misleading due to multiple sign-ins: “Litwak said his investigation found that Mr Molina had sometimes signed in to other people’s phones to check his Google account,” The Times reported.

“That could lead someone to appear in two places at once, though it was not clear whether that happened in this case.”

According to The Times, Google is the primary company that appears to be fulfilling the warrants (Apple says it can’t provide this information to authorities).

However, last year another company called Securus was reported to have obtained location data directly from telecoms that it then sold to law enforcement without a warrant.

A thriving black market in location data has persisted despite promises from carriers to stop selling it to middlemen, who divert it from intended uses in marketing and other services.

* Tom McKay is a staff writer for Gizmodo. He tweets at @thetomzone.

This article first appeared at www.gizmodo.com.au.