John Hawkins* says increasing numbers of governments are offering bonds with negative interest rates that are guaranteed to lose money.

In 1960, DC Comics introduced the “Bizarro” planet of “Htrae”.

In 1960, DC Comics introduced the “Bizarro” planet of “Htrae”.

Created with a duplicating ray, the planet’s inhabitants are all imperfect versions of Superman and Lois Lane, doing the “opposite of all Earthly things”.

They go to bed when the alarm clock rings.

They eat only the peel of a banana.

They earn degrees by failing subjects.

And they invest in “bizarro bonds” that are “guaranteed to lose money”.

Today, a bizarro bond is no longer comic-book fantasy.

Now the Governments of Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland are selling 10-year bonds with negative interest yields.

The normal attraction of a bond is that, for an upfront payment, the issuer pays you back more — paying interest on the principal over a given number of years, and the principal at the end.

Government bonds — which are the main way governments fund deficits — have been particularly attractive to investors wanting minimum risk, because a government can generally be relied on to pay its debts.

But bonds with a negative interest rate mean bond holders are effectively paying governments to hold their money for them.

The existence of these bizarro bonds, and the fact anyone wants to buy them, tells us much about how strange global economics now are, and that expectations are low about things changing any time soon.

Negative positives

Why would anyone want to buy such a bond?

The main reason is still the same.

A government bond is safe.

It’s just that now the bond doesn’t guarantee a minimum return but a minimum loss.

Take, for example, the Swiss Government bond that currently costs SFr103.15, pays no interest and will return just SFr100 when it “matures” in June 2029.

The holder knows they’ll lose more than 0.3 per cent over a decade, but no more.

A term deposit in a Swiss bank is no better, with interest rates of about –0.3 per cent, and less safe.

Buying shares or gold might return more but carries a bigger risk of losing a lot more.

For foreign purchasers, there is an additional consideration — they may be hoping the Swiss franc will strengthen against their local currency — but for Swiss citizens it largely comes down to paying the Government to keep their money safe.

Short-term rates

Bond yields reflect a number of factors, but the most crucial one is expectations about short-term interest rates as well as inflation.

Right now interest rates around the world are at historically low levels, and there is little expectation they will increase any time soon.

This is important because an investor can weigh the value of buying a 10-year bond against any other investment, particularly against buying a one-year government bond and then, when it matures next year, buying another one-year bond, and so on.

Suppose interest rates are about 1 per cent but everyone buying bonds expects rates to rise.

The 10-year bond would then need to offer a yield more than 1 per cent to be competitive with simply buying one-year bonds and rolling them over (on the basis the yield offered will more than 1 per cent next year).

The 10-year yield would need to match the average expected returns from one-year bonds over a decade.

The market for negative yields on 10-year government bonds in Japan and Europe therefore implies that most investors are expecting near-zero or negative interest rates will be maintained by central banks for some years to come.

The yields on government bonds still in positive territory imply something similar.

In Australia, for example, where the 10-year yield hit a historic low below 1.3 per cent in June, the implication is that markets expect the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to keep the cash rate at or below its current all-time low of 1 per cent for a considerable period.

All this suggests markets are not optimistic about global economic growth (possibly due to concerns about higher US tariffs).

It is the same with other long-term interest rates, such as term deposits offered by banks.

Implications

Negative interest rates are extremely rare.

Even rates as low as 1 per cent are historically unusual.

In his epic study, A History of Interest Rates (1963), author Sidney Homer suggests rates lower than 3 per cent were virtually unknown in ancient Mesopotamia, Greece or Rome, or in medieval and renaissance Europe.

Bank of England data show there were just three months between 1935 and 2012 when the yield on 10-year UK Government bonds dropped below 2 per cent.

Since mid 2015, they have not been above 2 per cent, and are now below 1 per cent.

For governments, this could be a rare opportunity.

It’s an ideal time to borrow.

This should make infrastructure projects more economically viable.

In Australia, RBA Governor, Philip Lowe has argued quite forcefully for more spending on infrastructure.

“This spending not only adds to demand in the economy, but it also adds to the economy’s productive capacity,” he said in June.

But “debt and deficit disaster” and “back in the black” rhetoric may mean the Australian Government does not seize this opportunity.

A government doing the opposite of the good advice given to it by a trusted central bank governor would be just what one expects in a Bizarro world.

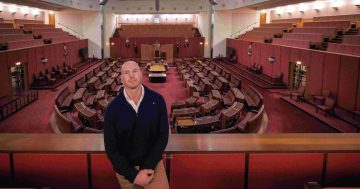

* John Hawkins is an Assistant Professor at the University of Canberra.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com.