Rhonda Garad and Helena Teede* say Australian women medical professionals continue to be disproportionately under-represented in senior positions.

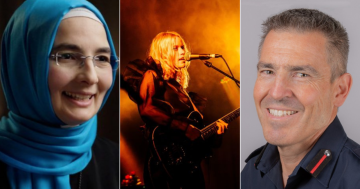

Photo: Marion Brun

When the highly esteemed Professor Priscilla Kincaid-Smith was a young doctor in the 1950s, she defied the Government of South Africa to work in the slums of Soweto.

“We worked seven days a week and just loved curing people of preventable illnesses,” she said.

“In South Africa I never experienced any opposition to being a woman in medicine.”

So, it came as a great shock to her when she migrated with her family to Australia in 1958 to find she was unwanted, and was, in fact, unemployable as a married woman.

“It was made very clear to me that I should stay home and look after our children, and that women were not accepted in senior medical roles in Australia,” she said.

“It bitterly disappointed me that men put up such strong opposition to appointing me to hospital and university positions.”

But Priscilla wasn’t a woman to be deterred and went on to become the first female professor at the University of Melbourne, first President of the College of Physicians of Australia, and the first woman President of the World Medical Association.

Despite her achievements, female medical graduates in Australia continue to be disproportionately under-represented in professional senior positions today, despite having attained gender parity in Australian medical schools for decades, and performing equally to male peers on measures of medical knowledge, communication skills, professionalism, technical skills, practice-based learning and clinical judgement.

Women represent only about 30 per cent of deans, chief medical officers, medical college board or committee members, and 12.5 per cent of CEOs in large hospitals.

There’s also a 33 per cent pay gap for full-time specialists, and a 25 per cent pay gap among full-time general practitioners.

Clearly, structural and cultural factors persist that impede both equivalent pay and the flow of women into senior and influential levels of the medical profession.

Gender equity refers to “fairness of treatment [for all], according to their respective needs”, which may include equal or different, yet equivalent treatment across rights, benefits, obligations and opportunities.

Equity underpins workforce diversity, embracing differences to create a productive environment where all are valued and talents and skills are optimally harnessed.

A diverse workforce represents society, understands and responds to community needs, embodies the principles of equity and diversity, and models the diffusion of prejudices and stereotypes, promoting a society free of discrimination.

The medical profession should embody, promote and lead on the delivery of these aspirations.

Working in the Monash University School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, one of the authors, Professor Helena Teede, has experienced less “conscious gender bias” in her career than Professor Kincaid Smith, but has been continually confronted by pervasive “unconscious bias”.

Reaching the level of Professor of Medicine at a young age, she was frequently mistaken for the secretary at meetings, and often found herself the “token” single woman on committees.

Professor Teede, who delivered the Royal Australasian College of Physicians Priscilla Kincaid-Smith Oration, says: “Whilst efforts to exclude women from leadership roles are increasingly uncommon, gender inequity in medical leadership persists.”

“Unconscious gender bias still contributes to the so-called glass ceiling or unspoken barriers to career progression, which prevail despite increased qualifications, employability and work performance among women.”

Professor Teede’s experience resonates with Dr Liz Sigston, a respected ENT, head and neck cancer surgeon at Monash Health.

“Women are often welcome in supportive roles, but when they try to make changes to the system, they start to feel a backlash,” she said.

“We have a much harder path to being seen as senior leadership material.”

A key problem is that unconscious bias is under-recognised, and as such is propagated in the current system that doesn’t support women to attain their career goals.

Evidence now shows that women are disadvantaged on the career and pay ladder in medicine due to issues around capacity (home and family responsibilities), perceived capability (confidence) and credibility (more limited female leaders and role models).

Issues such as recognition and support of the roles women (and increasingly men) perform encompassing family and work, flexibility at work, the vital need for mentoring, role modelling and leadership capacity-building, as well as addressing outdated non-inclusive leadership styles, are all important.

For change to occur, we need women and men to be individual champions, but we also need individual, organisational and policy-level action and reform.

The case for change is supported by Erwin Loh, Professor in Healthcare Leadership at Monash University, and Group Chief Medical Officer and Group General Manager, Clinical Governance, at St Vincent’s Health Australia.

“Individual male and female champions of change are needed, alongside organisational and systems-level change to achieve gender equity,” Professor Loh says.

Eliminating gender inequity broadly in health requires a paradigm shift from an organisational culture linking traditional masculine leadership styles and values with leadership credibility; to a distributive leadership model in which women’s strengths and leadership diversity more broadly can flourish.

It’s beholden on Australia’s current leaders to move away from perceived gender-characterised leadership styles, to identify non-inclusive leadership styles, recognise that the “behaviour we walk past is the behaviour we accept”, and to call out and address this behaviour that challenges credibility and diversity of leadership together.

Professor Teede’s team, including Professor Helen Skouteris, Associate Professor Jacqueline Boyle and PhD student Mariam Mousa, is now leading a large-scale national initiative with professional colleges, leading health services and Government to identify and address challenges at the individual, organisational and systems level.

“Through research and translation, we’re co-designing, implementing and evaluating effective strategies to enable gender equity and diversity more broadly and, where effective, these can then be scaled across our health system and beyond,” she said.

* Rhonda Garad is Senior Lecturer and Research Fellow at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation. Helena Teede is Professor (Research) at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation.

This article first appeared at lens.monash.edu.