Theodore Kinni* says today’s leaders can learn valuable lessons from James Webb, the NASA administrator who met John F. Kennedy’s lunar challenge.

NASA has set its sights on Mars. In April, the space agency flew a solar-powered drone on the red planet — the first powered flight on another world.

NASA has set its sights on Mars. In April, the space agency flew a solar-powered drone on the red planet — the first powered flight on another world.

A month earlier, it successfully fired up the four engines of its most powerful rocket since the Apollo era.

If the funding and political will can be sustained, this will be the rocket that lifts humans to Mars. James Edwin Webb would surely be delighted.

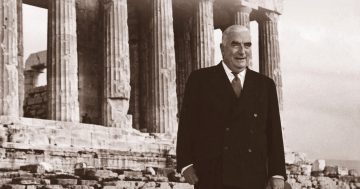

Webb was NASA’s second administrator, appointed by President John F. Kennedy in January 1961.

He led the agency through the early manned flights of the Mercury and Gemini programs and set the course for the Apollo lunar missions.

Webb resigned in October 1968, 18 months after three astronauts died in a cabin fire during a launch rehearsal for the first mission of the Apollo program.

His resignation came just a few days before the program successfully resumed with Apollo 7, and less than a year before Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon.

Kennedy chose Webb because, as Tom Wolfe wrote in The Right Stuff, “he was known as a man who could make bureaucracies run.”

Webb’s CV included private- and public-sector leadership. He had advanced from personnel director to treasurer to vice president at the Sperry Gyroscope Company, as it grew from 800 to 33,000 employees, and served as president of the Republic Supply Company, a troubled business that its parent, Kerr-McGee Oil Industries, sold at a profit thanks to his leadership.

In the public sector, President Harry S. Truman appointed Webb director of the Bureau of the Budget, and then, undersecretary of state to Dean Acheson.

“I do not know any man in the entire United States, in the Government or out of the Government, who has a greater genius for organisation, a genius for understanding how to take a great mass of people and bring them together,” said Acheson of Webb.

In January 1961, when the call came to lead NASA, Webb tried to avoid it.

He refused meetings with Kennedy’s science advisor and turned down a direct job offer from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson.

But when Webb found himself face-to-face with Kennedy, he was unable to refuse the insistent president. As if to eliminate any chance that Webb might yet escape, Kennedy promptly marched his new administrator from the Oval Office to the White House press office, where the appointment was announced to the media.

The keystone of NASA’s executive team, a man whom the New York Times would call an “extraordinary manager,” was in place.

Webb and his achievements at NASA are not as well-known as they should be.

The intense interest in the astronauts and their exploits, the Apollo 1 tragedy, and the passage of time have obscured his role in the first era of the space age.

But there are useful lessons in it for today’s leaders.

Team-based leadership

Webb wasn’t playing hard to get when he tried to avoid the top job at NASA.

“This was no matter of modesty,” he later explained.

“I would not have had the same hesitation about some other equally responsible task that was not so heavily concerned with the intricacies of advanced scientific knowledge and advanced technology.”

Webb overcame his lack of technical expertise by creating a leadership triad at NASA and by making all major decisions with his two principal deputies — Hugh Dryden and Robert Seamans.

Dryden was an eminent aeronautical scientist who had led the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics before it became the core of the newly formed NASA in 1958.

Seamans was a hands-on executive who was already instituting the processes and procedures needed to manage the fast-growing agency.

“The three of us decided together that the basis of our relationship should be an understanding that we would hammer out the hard decisions together, and that each would undertake those segments of responsibility for which he was best qualified.

“In effect, we formed an informal partnership within which all major policies and programs became our joint responsibility, but with the execution of each policy and program undertaken by just one of us,” explained Webb.

In forming a top team at NASA, Webb was putting into practice the ideas of Mary Parker Follett, the pioneering organisational theorist whose work he had studied.

Mission-setting

Sixty years ago, on May 25, 1961, Kennedy stood before a joint session of Congress and declared, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

Webb was instrumental in setting that seemingly impossible goal, but it was, in fact, a lesson in caution.

At the time, only one American astronaut had been to space, and only in a short, suborbital flight.

But NASA had informed Kennedy that a mission to the moon and back would be feasible by as early as 1967.

However, when Webb read a draft version of Kennedy’s address, which set that year as the target date for the moon landing, he argued for a change.

“Webb saw the need for what he called an ‘administrative discount,’ a margin of flexibility weighted against what the technical experts thought was possible, just in case something went wrong,” writes W. Henry Lambright in his terrific biography, Powering Apollo: James E. Webb of NASA.

“He did not want the prestige of the nation (much less his own reputation) resting on an overly optimistic deadline.”

Kennedy changed the speech — a wise move, given that the moon landing occurred in July 1969.

Organisational structure

Webb defined the main task of leadership as “one of continually organising and reorganising, directing and redirecting diverse human and material resources and complex activities under conditions that always contain elements of uncertainty.”

To this end, he ordered four major reorganisations at NASA during his eight-year stint as administrator.

In 1961, in order to unite NASA around the common objective of a lunar landing, Webb transformed the hitherto decentralised agency, adding five new program offices, which, together with existing field centres, would all report directly to the leadership triad.

In 1963, as the organisation coalesced around its mission, Webb again reorganised NASA — this time giving the field centres more power and having them report to the program offices.

In 1965, he reorganised NASA once more, creating an Office of the Administrator that had a larger functional staff to help the leadership triad manage the demands of the much larger and more active agency.

Finally, in 1967, Webb reorganised NASA to prepare for the completion of its mission; and then, in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire, to enable greater top-down control.

“During the 1960s, top NASA officials had to be ready to change when change was imperative,” writes Arnold Levine in Managing NASA in the Apollo Era, “and to refuse to accept organisational forms as important beyond the goals they might serve.”

Stakeholder management

Webb’s primary role in NASA’s leadership triad was to manage the external stakeholders on whom the agency’s funding and success depended.

He understood well the mechanics of the executive branch.

For instance, in 1964, Webb actively lobbied Congress in support of Lyndon Johnson’s historic civil rights legislation, and in return, he secured Johnson’s financial backing and influence for NASA’s initiatives.

Webb also knew how to corral congressional support.

In proposing that NASA move from Virginia’s Tidewater region to Houston, Webb secured the financial and political support of Albert Thomas, a powerful Texas congressman.

“Mr. Webb handled that,” explained Robert Gilruth, the first director of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center.

“He said, ‘We’ve got to move to Texas. Texas is a good place for you to operate. It’s in the center of the country. You’re on salt water. It happens also to be the home of the man who is the controller of the money.’”

Finally, Webb recognised the powerful effect of optics on stakeholder support.

When he discovered that liquor was being served on the plane NASA used to transport its executives, he ordered the practice stopped.

Then, when Seamans warned him that it would make for unhappy passengers, Webb replied, “They’ll be even less happy if Congress climbs on us for something as silly as that.”

If you were among the 650 million people who watched Neil Armstrong step onto the surface of the moon in July 1969, you surely remember that historic moment.

It’s also worth remembering that James Webb was its managerial architect and that today’s leaders can find good lessons in his achievement.

*Theodore Kinni is a contributing editor of strategy+business. He can be contacted on Twitter at @TedKinni.

This article first appeared at strategy-business.com.