Several regions across Queensland are on the brink of financial disaster, according to the McKell Institute report, mainly due to a series of climate disasters that have left insurers struggling to cope. Photo: Facebook/Cook Shire Council.

The sunshine state is bearing the brunt of Australia’s cost-of-living crisis, with significant levels of poverty and debt leaving Queenslanders at the end of their rope. However, a new report from the McKell Institute suggests a Community Financial Rights Service could have a significant impact on those facing financial hardship.

Unlike other states, the Queensland Government doesn’t offer a community service that provides free financial counselling or legal and social work assistance, despite Queensland’s Community Legal Centres supporting 50,973 people in 2022, of whom 73 per cent were facing financial distress.

According to the McKell Institute, a dedicated financial rights service with $5 million of funding per year would “not solve all their economic challenges overnight, but it would make a massive difference”.

Queensland executive director of the progressive public policy body, Sarah Mawhinney, said it’s a model that has proven remarkably effective and cost-efficient in other states, “so the template is there”.

“A Community Financial Rights Service in Queensland is long overdue — the 2024 election provides an opportunity to solve this stubborn inequity and bring Queensland into line with the rest of the country.”

Many states face economic disadvantages, but Queensland faces particular challenges, largely driven by its decentralised population.

The majority (75%) of disadvantage sits in areas beyond Brisbane, notably concentrated in the western and far northern regions of the state. Among the top 10 areas experiencing the most severe disadvantage, eight were situated outside the capital.

Remarkably, the latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) report found urban Queensland outside of Brisbane as the region with the highest likelihood of housing stress in Australia – followed by Sydney and nonurban Queensland.

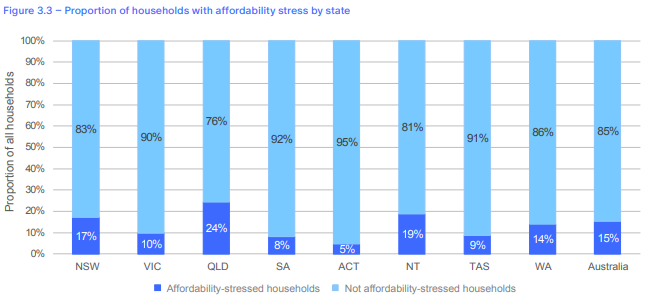

This graph shows how the 15 per cent of affordability-stressed households across Australia vary by state – with Queensland at the top. Source: Actuaries Institute.

Another issue is the frequency of natural disasters that are particularly damaging to the state’s north.

The Institute of Actuaries claims the number of uninsured properties has surged nationwide over the past two financial years, with premium increases of 25 per cent overall and 50 per cent in disaster-prone areas.

It’s been described as an emerging threat by the Reserve Bank of Australia. It believes the financial and insurance sectors may soon be forced to take action against loans for uninsured properties and businesses. This may include insurers adjusting premiums or withdrawing coverage from high-risk regions altogether.

Compounding this is the vulnerability of regional Queenslanders to predatory payday loan practices, which are even more accessible in the digital age.

Caxton Community Legal Centre in Brisbane’s CBD has partnered with Uniting Care to trial the proposed integrated support service.

Its CEO Cybele Koning said they have lawyers specialising in financial rights working with social workers and financial counsellors all “under the one roof to meet the complex needs of vulnerable people”.

The McKell Institute claims Victoria’s Consumer Law Action Centre efficiently addresses common issues like consumer guarantee and contract breaches. But workers can also seek advice on complex matters like irresponsible lending and unconscionable conduct.

Group executive of family and disability services at Uniting Care, Donna Shkalla, said a collaborative model of support like this can help people across Queensland who are facing significant challenges and stress.

“People across Queensland are facing significant challenges and stress,” she said.

“Too often, individuals must deal with intricate and confusing consumer concerns, which can negatively impact their financial, emotional, and even physical wellbeing.

“A collaborative model of support that promotes financial justice for people from a social, financial, and legal perspective will help people overcome these obstacles and have the potential to alleviate so much pressure on families and communities.”