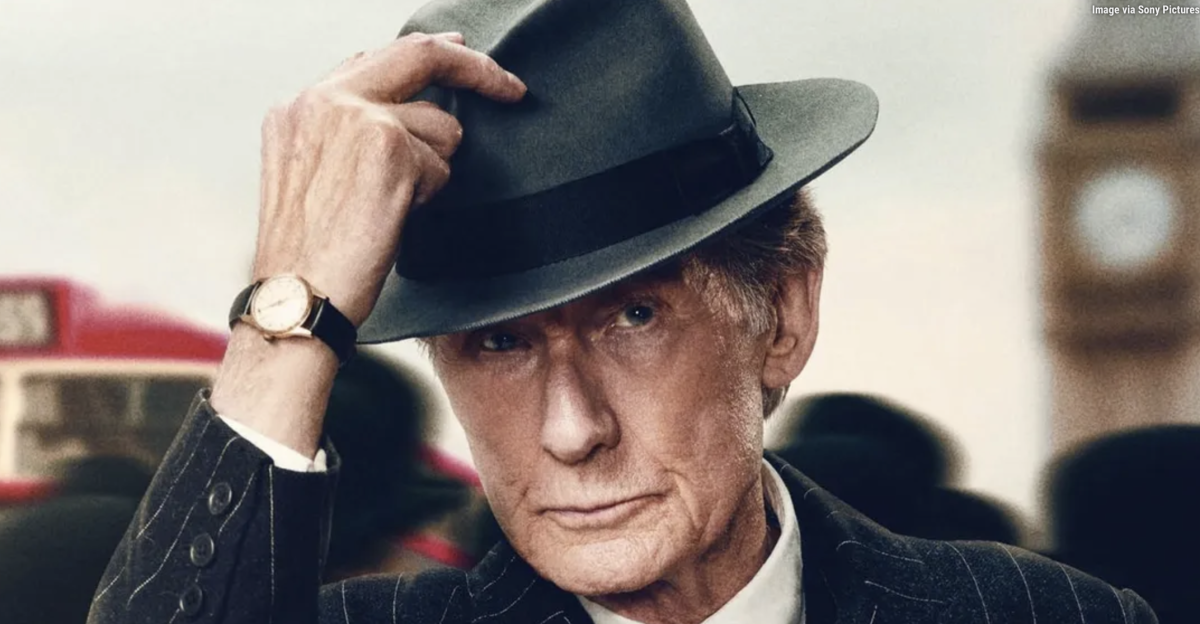

Bill Nighy gives a career-defining performance as a man facing the end of his life. Photo: Supplied.

As Living opens, Mr Williams is an ageing bureaucrat in a dead-end job, running a small section in a local government department near London.

With every new complaint or inquiry, the paperwork simply gets shelved where it can wait another day or never be acted on.

Having already visited a doctor for an unknown complaint, he returns to be diagnosed with inoperable terminal cancer and is given six or so months to live.

How does he tell his son and daughter-in-law who live with him? He can’t, because he feels it would be too much of a burden and prefers the stiff upper lip.

So Mr Williams takes an extended period of leave from work, first spending a night carousing with a local in a nearby seaside town, at the end of which he sings an old Scottish folk song from his youth, ‘The Rowan Tree’.

The audience is enthralled, but the moment is brief.

On his return to his home, he stumbles across a young woman, Margaret Harris, who works in his office but is about to leave and needs a job reference. He obliges while also treating her to lunch at the prestigious Fortnum and Mason store.

They strike up a close friendship and spend time together and she tells him people will talk, “they’ll think you’re infatuated with me”.

He says he is infatuated, but more with her love for life than anything else. Then he tells her that he’s doing this because he is about to die.

Back in the bureaucracy, a group of three women have been pestering the office for some time. They want to have a playground built on a rubbish dump site filled with sewage.

Mr Willaims clearly believes if he can get the playground built, his life will have meant something more than just being a gentleman.

Living is directed by Oliver Hermanus, a South African director with a handful of impressive films behind him (Shirley Adams, Beauty).

What struck me most was the narrative power delivered by the screenplay’s author, Nobel Prize-winning Japanese/British writer Kazuo Ishiguro (The Remains of the Day, Never Let Me Go, The Unconsoled, When We Were Orphans).

The film is set in the 1950s and is based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 drama Ikiru (To Live), which he co-wrote with two other legends of the Japanese artistic world, Shinobu Hashimoto and Takashi Shimura.

I think Ishiguro was quite deliberate in setting the time frame for this film.

Britain was emerging from the Second World War. People wanted to put the horror behind them and return to some sort of order, so for the upper middle class, it was all about show – suits, bowler hats, little if any conversation and a willingness to put off any decisions of substance.

But like Remains of the Day, both the book and the film, Ishiguro places difficulty and intransigence next to empathy and kindness, which can be, and is, quite an enticing combination.

Mr Williams, with only a short time to live, finally sees past social artifice. Even if he does something small like getting a playground built, it will mean so much to those children, providing lifelong memories. The smallest acts can often bear the greatest gifts.

Living is completely owned by Bill Nighy who plays Mr Williams.

As the layers peel away, this previous husk of a man becomes warm, engaging, caring and, most importantly, as the title suggests, alive.

It’s a career-defining performance from Nighy, who completely takes over the screen for every single moment. A raised eyebrow, a grimace, a smile are tiny in themselves but amplified in so many subtle ways by the circumstances in which we find them.

The supporting cast is also very good, especially Aimee Lou Wood as Miss Harris, and Alex Sharp as one of Mr Williams’ colleagues, Peter Wakeling.

I’m not giving away any spoilers, but at the end of the film, long after Mr Williams dies, we see a flashback of him sitting on a swing in the children’s playground singing ‘The Rowan Tree’. I’m just going to say, there was not a dry eye in the house.

Yes, Living is a sad film, but it is also filled with so much hope. In fact, I found it exquisite: four and a half stars out of five.

Living is screening at major cinemas.

Marcus Kelson is a Canberra writer and critic.

Original Article published by Marcus Kelson on Riotact.