Melanie Ehrenkranz* claims researchers have developed yet another unnerving new method of creating deepfake videos.

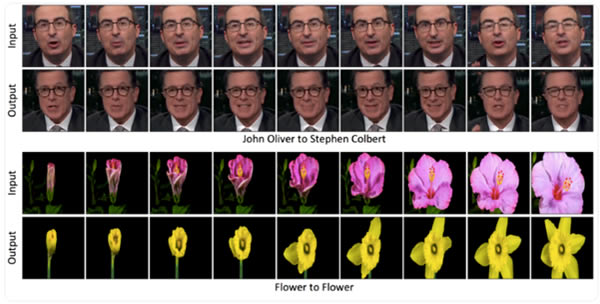

Carnegie Mellon’s video retargeting. Top row shows morph from John Oliver to Stephen Colbert and bottom row a flower.

Deepfakes — ultrarealistic fake videos manipulated using machine learning — are getting pretty convincing.

And researchers continue to develop new methods to create these types of videos, for better or, more likely, for worse.

The most recent method comes from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, who have figured out a way to automatically transfer the “style” of one person to another.

“For instance, Barack Obama’s style can be transformed into Donald Trump,” the researchers wrote in the description of a YouTube video highlighting the outcome of this method.

The video shows the facial expressions of John Oliver transferred to both Stephen Colbert and an animated frog, from Martin Luther King Jr to Obama, and from Obama to Trump.

The first example seen — Oliver to Colbert — is far from the most realistic manipulated video out there.

It looks low-res, with certain facial features blurring at certain points.

It’s almost as though you’re trying to stream an interview from the internet but you have incredibly weak Wi-Fi.

The other examples (excluding the frog) are certainly more convincing, showing the deepfake mirroring the facial expression and mouth movements of the original subject.

The researchers describe the process in a paper as an “unsupervised data-driven approach”.

Like other methods of developing deepfakes, this one uses artificial intelligence.

The paper doesn’t exclusively deal in translating talking style and facial movements from one human to another — it also includes examples with blooming flowers, sunrises and sunsets, and clouds and wind.

For the person-to-person deepfakes, the researchers cite examples of how certain mannerisms can be transferred, including “John Oliver’s dimple while smiling, the shape of mouth characteristic of Donald Trump, and the facial mouth lines and smile of Stephen Colbert”.

The team used videos available to the public to develop these deepfakes.

It’s easy to see how these techniques might be applied in a more innocuous way.

The example of John Oliver and the cartoon frog, for instance, points to a potentially useful tool when it comes to developing realistic, anthropomorphic animations.

But as we’ve seen, there are consequences to the proliferation of increasingly realistic deepfakes — and equipping bad actors with tools that make them cheap and easy to create.

In time, they may dangerously mislead the public, and can serve as a nefarious tool for political propaganda.

* Melanie Ehrenkranz is a reporter for Gizmodo. She tweets at @MelanieHannah.

This article first appeared at www.gizmodo.com.au.