University of Tasmania PhD candidate Mel Wells on King Island with a little penguin during a study on PFAS contamination in marine and coastal environments. Photo: Jaslyn Allnut.

Following a Right to Information (RTI) request by Friends of the Earth (FOE), the Tasmanian water authority revealed that PFAS chemicals were found in almost all samples taken from 29 Sewage Treatment Plants (STP) around the state.

The environmental organisation’s Australian branch received the information in December, which was obtained by TasWater’s study on the group of more than 4000 chemicals representing per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

According to the government, historically the chemicals have been used in firefighting foams, and increased levels are being detected at sites such as airports, defence force bases, industrial areas, effluent outfalls and landfill sites.

However, the properties that make them especially useful also make them dangerous for the environment. PFAS chemicals of greatest concern are highly mobile in water, do not fully break down naturally in the environment, and are toxic to a range of animals.

An understanding of the long-term impacts of human exposure to PFAS is still being developed, yet many countries have discontinued or are phasing out their use.

Since 2002, the federal government has sought to reduce the use of certain PFAS. But recently, scientists from the University of Tasmania found widespread evidence of these ”forever chemicals” across marine and coastal environments.

According to the PhD study by the School of Natural Sciences and Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), 14 PFAS were detected in nesting soils, blood and abandoned eggs of little penguins.

Study lead author and PhD candidate Mel Wells said they detected PFAS in 100 per cent of the samples collected from Burnie and Hobart’s Derwent estuary.

“We found that PFAS concentrations were positively associated with increased urbanisation around penguin colonies,” Ms Wells said.

“These results indicate a detectable reduction to general health as a result of PFAS exposure and possible evidence for diseases, but more research is needed to verify this.

“This is a real health risk to biological life, especially to marine predators like seabirds, seals and dolphins. And because we consume seafood exposed to PFAS, it’s also a risk to human health.”

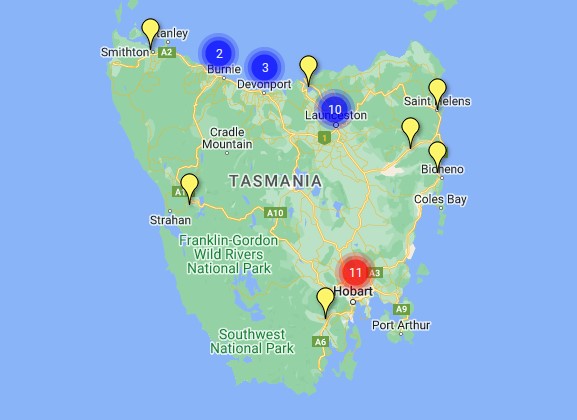

Friends of the Earth’s map showing the positive PFAS samples detected across Tasmania, more information on which can be found on the group’s website. Photo: FOE.

In Tasmania, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified several PFAS contamination sites, which the State Government is expected to manage under its action plan. The locations include Hobart and Launceston Airports, the Tasmanian Fire Service Cambridge Facility and the Australian Maritime College Bell Bay Fire Training Centre.

In proximity to Hobart Airport is the Cambridge STP, which was found to be the worst-performing site of those sampled in the RTI data ascertained by FOE. This was due to the main PFAS chemical of concern, PFOS, accounting for 88 per cent of the detections made at the site.

Of all the tested STPs, 76 per cent breached the lower end of the proposed National Environment Management Plan (NEMP) guidelines for PFHxS+PFOS for biosolids/sludge; but only 7 per cent for PFOA chemicals.

While TasWater information regarding STP influent coming into treatment plants was limited, all four of the tests conducted in a drinking water supply for Hobart came up negative.

FOE land use researcher Anthony Amis raised whether a buyer of biosolids from TasWater or water authorities elsewhere in Australia would take legal action over contamination of farmland where biosolids had been used.

“What procedures are currently in place to notify landowners about the PFAS content of the biosolids that they are using?” Mr Amis asked.

“Given that biosolids have been sold for decades, the issue of PFAS accumulation on farmland should not be discounted.”