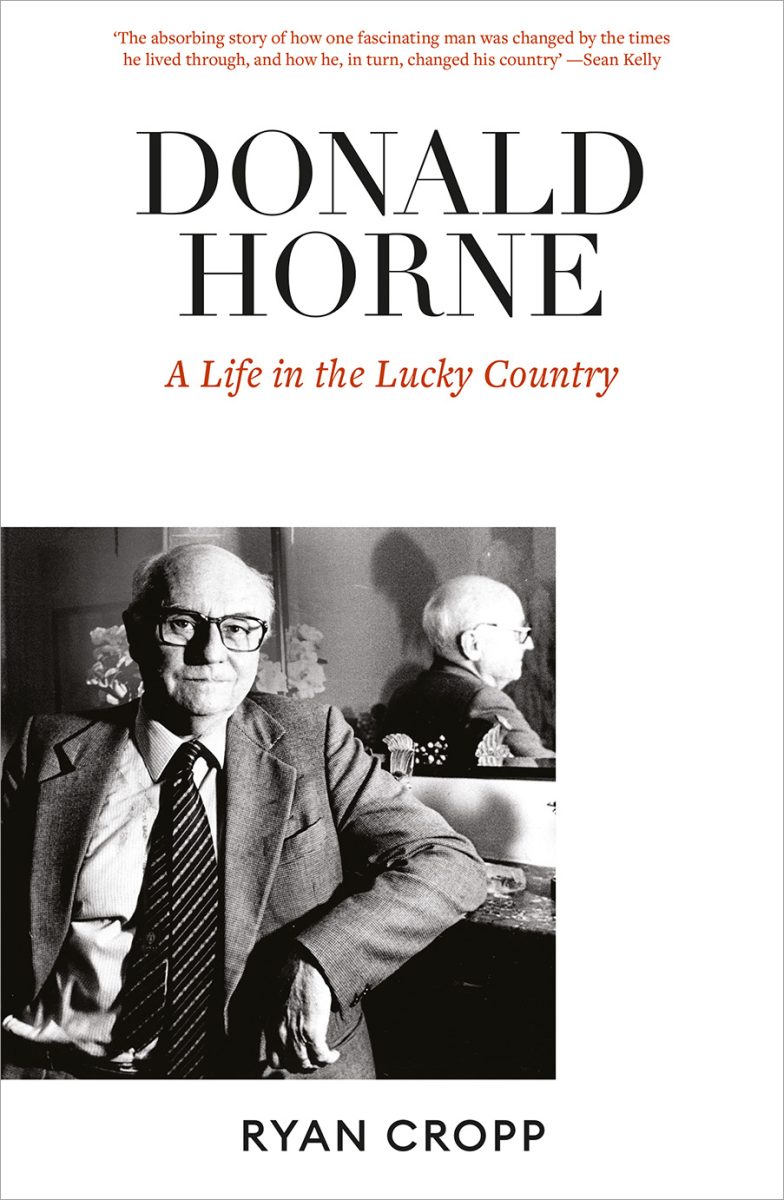

Donald Horne: A Life in the Lucky Country is a captivating biography of one of Australia’s best-known public intellectuals. Photo: Supplied.

By Ryan Cropp, La Trobe University Press, $37.99

One of Australia’s foremost academics, historians and philosophers, Donald Horne, author of The Lucky Country, “was no ordinary Australian talking head”.

Some profound words. Through the eyes – and indelible words – interwoven seamlessly by Ryan Cropp, we get an intelligible sense of the man at the centre of this fascinating biography: a brilliant man who captured the nation’s imagination and boldly showed Australians who we were and how we could change.

In the 1960s, Donald Horne offered Australians a compelling reinterpretation of the Menzies years as a period of social and political inertia and mediocrity. The Lucky Country was profoundly influential and, without a doubt, one of the most significant shots ever fired in Australia’s endless culture war.

Meticulously researched, Cropp’s landmark memoir positions Horne as an antipodean Orwell, a lively, independent and distinct literary voice “searching for the temper of the people, accepting it, and moving on from there”. He is uncannily sharp-eyed and eloquent, as we see a recognisable modern Australia become visible.

As he elaborates, writing The Lucky Country was an experience that taught Horne many new things, both about the country and about himself.

“The most fundamental, he thinks, was the need to abandon much of what he had been taught about Australia,” Cropp wrote.

“While writing the book, he had tried to unlearn the artificial ways that the country had previously been analysed and interpreted. Doing so had forced him to see the world anew, in the way he had as a boy, taking things as they came.

“The man providing this public self-analysis, Donald Horne, was, by vocation, a social critic, someone who trafficked in serious ideas and arguments, famous for thinking rather than doing. He was, in effect, an intellectual celebrity.”

Few Australian phrases are as memorable – or have redefined reality as successfully – as ‘the lucky country’. In the six decades since Horne coined it, it has invaded the language, contorting and evolving with each new use. It is deployed freely and interchangeably, either as a celebration of Australia’s unique virtues, a criticism of its unique vices, or – most often – simply as a glib synonym for the nation itself.

Horne lived in the shadow of the phrase for much of his life. Within months of the book’s publication, the phrase was being used in slogans and advertisements.

As Cropp points out, in certain moods, Horne would decry its existence and insist he was sick of being asked about it. More often, though, he was ambivalent about its long afterlife.

“It was in the end, a source of authority and prestige, the platform from which he launched his long and incredibly productive career as a writer and public figure,” he wrote.

For Horne, who was not easily typed, unforgettable phrases were masterpieces.

As a writer and critic, Horne had a natural inclination to draw meaning from the personal and the everyday, to make sense of the meaninglessness of existence.

According to the Sydney-based author: “[Horne] was always taking a look around, always peering out the bus window and thinking carefully about what he saw.

He was constantly absorbed in and fascinated by the world, forever seeking out new ideas and images for analysis, interrogation and categorisation. He was interested in anything and everything, untroubled by constraints of discipline or expertise. His friends sometimes described him as a bowerbird: collector and an arranger of ideas and events, relentlessly trying to make new patterns out of the increasing complexity of postwar society.”

Beautifully crafted, historian Ryan Cropp ingeniously meets the challenge to eloquently recognise an expressive and unified ideology.

“It is my hope that in a critical account of the images that Horne ‘cast up’, it will once again be possible to see some of the roads by which Australia became what it is.”