Kevin Sieff and Gabriela Martínez* say Mexican women recently went ‘on strike’ to protest a horrific increase in femicides and lack of women’s rights.

What does a country look like without women?

What does a country look like without women?

On 9 March, in one of the world’s largest, busiest cities, Mexico City, it was a thought experiment that came to life, as women removed themselves from public view.

They didn’t go to offices, or restaurants or government buildings.

They didn’t go to school.

They didn’t ride in cars or buses or subways.

For a day, they were gone.

Mexico has been shaken by an increase in femicides — women and girls killed for their gender — several of them particularly gruesome.

In February, the body of 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was found skinned and disfigured.

Then the body of seven-year-old Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett Antón, abducted outside her primary school, was found naked in a plastic bag.

Those deaths invigorated this country’s longstanding women’s movement, which has clashed with successive governments that they say have done little to protect women.

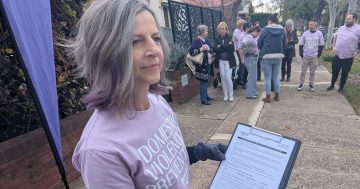

In recent weeks, protesters have marched outside the national palace; they scrawled the words “Femicide State” on its ornate doors.

On International Women’s Day, authorities estimated that at least 80,000 people marched through the centre of the city.

But on the morning of 9 March, after weeks of planning, women across Mexico protested by attempting to disappear completely.

“On the 9th, No Woman Moves,” was one protest mantra.

Organisers called it “A Day Without Us”.

Offices in both foreign and Mexican-owned businesses were half-empty.

Many, in cities across Mexico, declined to open.

Large employers such as Walmart and the baked goods giant Bimbo gave female employees the day off.

Women at Google, WeWork and Hooters stayed home.

The Mexico City branch of Coparmex, an influential employers’ association, said the economic losses in the capital alone could hit US$528 million.

The movement grew so big that even the Government — a target of the protest — agreed to participate.

Mexico City Mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo said female employees who stayed away would not be penalised.

Women at the Foreign Ministry left pieces of paper with statements on their empty seats.

“By the end of the day, 10 women will have been murdered. Stop killing us,” read one.

Public schoolteachers left signs in their classrooms explaining their absence.

“I didn’t come because I don’t want my female students or my daughter to be abused, humiliated or beaten,” a sign at a Mexico City school read.

At Bosque de Niebla, a small cafe in the Coyoacan neighbourhood of the capital, Cecilia Lynn Sueños told her all-female staff days in advance that the shop would shut.

“The protest is an attempt to make visible the work of women and to unite behind the feminist demands of today,” Sueños said.

She said it was partly aimed at the Government — “because they should be the ones to ensure that laws really do protect the human rights of women”.

She said she and her employees would devote the day to reading about and discussing feminism.

She would pay them for a normal day of work.

Other women said they supported the protest but couldn’t participate themselves — they weren’t offered the option of staying home with pay.

“I work because I need to pay rent,” said Nadia Iglesias, who plays a barrel organ near the city centre.

“I need to pay for my kids’ school.”

Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador said he supported the protest, but he also suggested that the women’s movement harboured elements hostile to his presidency.

“This movement has various aspects,” he said during his morning news conference on 9 March.

“It’s a movement of women who legitimately fight for their rights and against violence, against femicides.”

“But there is another part that is against us, and what they want is for the Government to fail.”

The President has said rising gender-based violence does not reflect the failings of his government, but rather a deepening “social decomposition” produced by previous Mexican leaders.

He has blamed femicides on neoliberal values and has expressed fatigue at addressing the issue publicly.

On 9 March, he called some of the women “conservatives disguised as feminists” and said they were hijacking the issue to destroy his government.

That response has left many women in Mexico unsatisfied.

Some have been outspoken in their anger toward López Obrador.

“The President has been provoking us with his indifference, with his comments,” said Guadalupe Loaeza, a well-known Mexican writer and journalist.

“He does not grasp that this is about feminism.”

“He misrepresents it, distorts it by saying that it is conservatism.”

Loaeza, too, stayed home.

“My husband already made me breakfast,” she said.

“I am not going out.”

“He already went out to buy food.”

“He is going to take care of everything today.”

* Kevin Sieff is Washington Post Bureau Chief for Mexico and Central America. He tweets at @ksieff. Gabriela Martinez is a Mexican print journalist.

This article first appeared at www.washingtonpost.com/world.