In part 1 of this story, we looked at the three main options the RAAF will consider for its next tranche of combat aircraft under project AIR 6000 Phase 7, a decision on which is expected in 2023.

In this follow-up article, we’ll look at what other options and complementary capabilities may also be considered.

The KC-30A multi-role tanker transport (left) and E-7A Wedgetail command and control aircraft have capabilities considered among the world’s best, but does Australia have enough of them? Photo: Defence.

Apart from the options laid out in Part 1, some analysts – particularly those from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) – have suggested Australia consider buying the US Air Force’s new Northrop Grumman B-21A Raider stealth bomber, the unveiling of which is scheduled for 2 December. The US was previously unwilling to release its most exotic capabilities for sale, even to its closest allies, but this may now be possible under the AUKUS construct. But with the B-21 likely to cost more than $A1 billion per aircraft and at least double that to build new facilities and establish a sustainment capacity, a squadron of 12-15 aircraft will cost about $30b. Therefore, this appears to be an unlikely proposition.

The secretive and stealthy Northrop Grumman B-21A bomber is due to be unveiled in December. Image: Northrop Grumman.

Another option that has been discussed is the USAF’s new Boeing F-15EX Eagle II. Based on the F-15E Strike Eagle, which first flew in the 1980s, the latest EX features advanced avionics, electronic warfare systems, and flight controls. While not stealthy like the F-35, it can employ a vast array of long-range weapons from stand0ff distances, and would make an ideal platform from which to control formations of uncrewed aircraft such as the MQ-28A Ghost Bat. But the RAAF already operates the F/A-18F Super Hornet, which, while neither as fast nor as capable as the F-15EX, is already in service, its sustainment system is mature, and it would be far easier and cheaper to just add to this fleet rather than introduce a whole new aircraft type.

The F-15EX offers a greater load, speed and range than the RAAF’s F/A-18F Super Hornets, but at what cost? Photo: US Air Force.

By 2030, the RAAF will likely have grown its current air combat fleet of 108 fighters – comprising 72 F-35As, 24 F/A-18Fs and 12 EA-18G Growler electronic attack aircraft – to as many as 136 manned or crewed aircraft. Those extra aircraft will also require additional pilots, engineers, logisticians and other personnel to maintain the capability. Short of a national mobilisation in a wartime scenario, ”growing” these people and support systems will be difficult, and may take a decade or more to achieve.

Using a well-worn but valid cliche, fighter pilots are generally considered the ”best of the best”. While most pilot candidates have a goal to fly fast jets, the vast majority won’t succeed. Instead, they may be ”streamed” off during their training to fly transport aircraft, tanker transports, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft, become instructors, or even operate the rapidly growing number of uncrewed aircraft from ground control stations. Some pilot candidates may not even be deemed suitable to be pilots at all, and may instead be offered airborne or ground-based aircrew positions, all of which are highly skilled roles in their own rights.

While the ADF keeps the actual numbers close to its chest, it is believed that, for every 100 pilot candidates the air force accepts, fewer than 10 will be posted to a frontline fighter squadron. Therefore, to find pilots for an additional 28 fighter aircraft, and without allowing for retirements, promotions, other new capabilities and general turnover, the ADF must recruit an additional 300 pilot candidates in the next five to six years.

Fewer than one in 10 of the RAAF’s pilot candidates will make it through to fast jets, so recruitment will need to be ramped up to meet a larger fighter force. Photo: Defence.

The RAAF introduced a new basic and advanced pilot training system in the past decade. While it has been designed to produce pilots better suited to a new generation of aircraft and their advanced systems, the system has had difficulty in achieving the throughput to meet current requirements due to issues with the courseware, simulators and aircraft availability. These have contributed to training system bottlenecks that are only just starting to clear now.

But even if the training and recruitment issues can be addressed, the air force will also need to consider the acquisition of other complementary capabilities to operationally support a greater number of combat aircraft.

The RAAF currently operates seven KC-30A multi-role tanker transports (MRTT), arguably the world’s best airborne tanker. But many analysts have suggested this is a bare minimum for the current force, and that at least five more would be far more suitable. Similarly, the current fleet of six Boeing E-7A Wedgetail airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft – also a world’s-best capability – is still considered to be at the lower end of what an operational capability should be.

And then there are basing considerations. Currently, Australia has just three permanent airbases in the country’s north capable of supporting combat aircraft operations – Tindal and Darwin in the Northern Territory, and Townsville in Queensland. It also has three ”bare-bones” bases – one each in the Pilbara and Kimberley in WA, and one on Cape York in Queensland – which are usually unoccupied but can be activated to support combat operations at a couple of weeks’ notice.

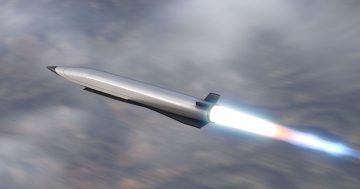

The ADF has several air defence projects underway that are due to mature in the next decade and which will be networked and operated under a centralised command and control system. But this plan will need to be expanded significantly to be able to defend these bases from possible ballistic and cruise missile attacks.

So, as you can see, it’s not just a matter of buying 28 more fighter aircraft.

Original Article published by Andrew McLaughlin on Riotact.