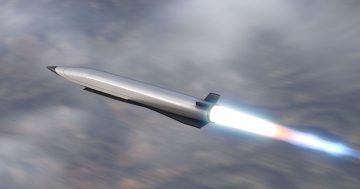

The HACM is a joint venture between Raytheon and Northrop Grumman, with cooperative development from the RAAF through the SCiFIRE program. Photo: Raytheon.

Australia will soon be at the leading edge of a new US Air Force hypersonic missile program.

Called the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM), a teaming of defence giants Raytheon Missiles & Defense, and Northrop Grumman was awarded a US$985 million (A$1.5 billion) contract on 22 September to develop the system.

The contract will cover the design, development, and initial deliveries of the HACM, and will be done in conjunction with the Royal Australian Air Force under the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE) joint initiative, a 15-year science and technology research collaboration into hypersonic scramjets, rocket motors, sensors, and advanced manufacturing materials.

In a November 2020 release, US Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, Michael Kratsios said, “SCIFiRE is a true testament to the enduring friendship and strong partnership between the United States and Australia. This initiative will be essential to the future of hypersonic research and development, ensuring the US and our allies lead the world in the advancement of this transformational warfighting capability.”

Also in November 2020, former RAAF Chief Air Marshal Mel Hupfeld said, “The SCIFiRE initiative is another opportunity to advance the capabilities in our Air Combat Capability Program to support joint force effects to advance Australia’s security and prosperity, working with our Defence scientists here in Australia and our partners in the US Air Force and across the US Department of Defense on leading-edge capabilities.”

The DF-17/DF-ZF has been displayed at military parades in Beijing, and combines a DF-17 ballistic missile rocket booster and a hypersonic glide body. Photo: Chinese Television screen capture.

Apart from the involvement of ADF and scientific personnel, another benefit is that the HACM program is likely to undertake a large proportion of its flight testing at the vast Woomera Test Range in South Australia.

The HACM is designed to initially be launched from tactical fighter-sized aircraft like the RAAF’s F-35A and F/A-18F Super Hornet, and possibly maritime patrol aircraft like the P-8A Poseidon. It will be powered by an air-breathing scramjet engine which Raytheon describes as using high vehicle speed to forcibly compress incoming air before combustion, thus enabling sustained flight at hypersonic speeds of Mach 5 or greater.

Raytheon and Northrop Grumman were selected for HACM over rival bids from Boeing, and Lockheed Martin, after all three bid teams were previously awarded design and development contracts in 2021. Designed to enter service in 2027, HACM is one of five known US hypersonic and acronym-rich missile programs in development.

The others include the US Air Force’s Lockheed Martin AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) which is a larger and longer-range weapon designed to be launched from a bomber, and which after several failures, conducted its first successful test flight in May 2022.

The US Navy is developing the Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) system, a hypersonic boost-glide missile program to develop a system that can be launched from surface ships and submarines. The US Navy also has its own Hypersonic Air-Launched Offensive (HALO) anti-ship missile requirement which is designed to be launched by aircraft carrier-based aircraft, but which otherwise appears on face value to align with many of the same requirements as HACM.

Not to be outdone, the US Army is running the unimaginatively-named Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) program which is aiming to also develop a hypersonic boost-glide weapon for fixed and mobile surface-launched applications.

The long-range ARRW is designed to be launched from bomber aircraft, and conducted its first successful flight in May 2022. Photo: USAFA.

But the US has been slow to realise the benefits of hypersonic weapons, with both China and Russia reported to have not only developed, but operationally fielded such systems.

China has developed the DF-ZF hypersonic boost-glide weapon which is surface launched atop a DF-17 missile booster. The system was reportedly flight tested between 2014 and 2017, and was declared operational in 2019.

Meanwhile, Russia has adapted its surface launched Iskander ballistic missile for air launched applications, and has reportedly employed it over Ukraine. Carried by the MiG-31 supersonic fighter, the Kinzhal missile is launched at high speed and high altitude, and flies a lofted ballistic trajectory to its target.

Where the Chinese and US systems differ from the older Kinzhal is in their ability to manoeuvre during their run in to their target, making them much more difficult to defend against than a more traditional – and predictable – hypersonic ballistic missile.

But rather than being an unpowered warhead that is propelled to hypersonic speeds by a rocket booster before gliding to its target – i.e. boost-glide – HACM is unique in that its scramjet engine will instead power it all or most of the way to the target, possibly allowing for greater manoeuvrability, and more control for enroute retargeting.

Original Article published by Andrew McLaughlin on Riotact.