Hannah Reich* says digital artist Chris Rodley is exploring whether artificial intelligence could spell the death of the artist as we know it.

“O, if you were a feeble sight, the courtesy of your law,

Your sight and several breath, will wear the gods.”

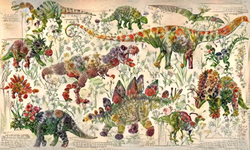

‘Deep Dinosaur’ by artist Chris Rodley.

You might mistake this for Shakespeare at first glance — and you’d be kind of right, but also wrong: despite all the signature frills and contortions of early modern English, this passage was actually generated by a recurrent neural network (RNN) — a type of artificial intelligence (AI).

RNN might not be giving Shakespeare a run for his money — yet — but it is part of a wave of experiments in computer-generated art that are calling into question the idea of the “artist” as we know it.

Chris Rodley, a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney who makes his own computer-generated art, thinks it could be a watershed moment.

“What I think we’re going to see with AI is perhaps a gradual erosion of this idea that artists have this absolutely unique insight that really puts them on this other plane from the rest of us,” he says.

Making art from algorithms

Rodley has been looking at the history of AI-generated literature as part of his PhD, as well as “tinkering” with coding and computer programs to generate art and writing.

One of his best-known works mashes up images of Sesame Street characters and the extended Trump family, using an algorithm called neural-style transfer (developed by researchers at the University of Tübingen).

The neural-style transfer algorithm allows the style of one artist to be transposed on to the shape of another image (for example, you can generate a Picasso-style selfie).

It does this by identifying pareidolic elements of each image.

Rodley explains: “Pareidolia is that phenomenon of looking at a cloud and thinking that it looks like a boot or Italy.”

Using the neural-style transfer algorithm, Rodley has also transferred the style of old lithographs of flowers on to the shapes of dinosaurs.

“That’s something I think humans would find hard to do because it requires such a fine level of detail,” he says.

“So, I’m interested in finding what the medium does that’s special.”

Rodley likens this current period of AI-art experimentation to the early days of filmmaking, when filmmakers had to figure out how to best work with the new technology.

“I think that’s what we’re seeing now with AI artists and writers — [we’re] working out what is the toolkit of artistic techniques.”

Machine learning

“AI is the broad area of technology that seeks to emulate human skills or human abilities,” explains Rodley.

Most of the digital art Rodley generates uses a recent form of AI called deep learning, based on deep neural networks.

“Neural networks are sort of these brain-like algorithms,” he explains.

Recent increases in computing power have enabled computer scientists to create neural networks that, for the first time, approach human abilities.

“The key thing for people to understand is that this allows computers to do all that instinctual stuff that humans do without thinking about it,” Rodley says.

Deep learning means AI can now recognise the sound of a voice speaking in a windy place or a cat on a dark night.

You’ve probably already encountered deep learning, whether it’s Google Translate, predictive email replies, or facial recognition software.

Death of a playwright

Earlier this month, Rodley read several AI-generated texts at a Melbourne Writers Festival event provocatively titled “Staged: Death of a Playwright”, alongside theatre scholar Rachel Fensham.

He also gave audiences a “potted history” of “the technologists trying to create machines that perform”, which he traces back to the automata of ancient Greece.

AI-generated text emerged in 1953, at the dawn of computing, when British computer scientist (and colleague of Alan Turing) Christopher Strachey created a “love letter generator”.

In 1966, we got the first chatbot: Eliza, created by the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

The development of deep neural networks has fuelled a “burst of creative activity” in the past 10 years, Rodley says, including a breakthrough moment in 2015 when computer scientist Andrej Karpathy used recurrent neural networks to generate writing in the style of Shakespeare.

Rooting for humanity

While deep neural networks have managed to replicate different styles of art and writing, artificial intelligence has yet to master plot or comedy.

“Language is still the most difficult nut to crack,” says Rodley.

“So there is some hope for those who are still rooting for humanity.”

But for humanity generally, the increasing ability of AI to emulate human interaction has big implications.

Recurrent neural networks are responsible for Twitter bots and spam bots, both of which were rampant in the 2016 US election.

And AI is already in our homes.

“The most astonishing thing for me now is the rise of smart speaker technology, home robots like the Amazon Alexa and Google Home,” Rodley marvels.

He planned to end the Melbourne Writers Festival event with “a machine-produced and machine-performed dialogue between two of these devices”.

“That’s really interesting because it’s a dynamic interaction, [so] nobody knows where it’s going to go next.”

* Hannah Reich is a digital producer for ABC RN’s The Hub, ABC Arts and The Messenger Podcast in Melbourne. She tweets at @hannahsreich.

This article first appeared at www.abc.net.au.