The new batteries are expected to offer a range of 1200 km. Photo: James Coleman.

Imagine an electric vehicle that’s lighter, can go further on a single charge and is less likely to catch fire if the battery is damaged in a prang.

That would be the transport equivalent of the elixir of life.

You can understand the excitement, then, when Toyota revealed an “advanced battery technology roadmap” in September last year, with mention of a “technological breakthrough” for a new type of battery that’s been “long seen as a potential gamechanger for BEVs”.

And not just because Toyota was saying it, a company that up to now has been reluctant to jump on the EV bandwagon.

The tech is called ‘solid-state’ and the aim was for the new batteries to be ready for use in 2027 or 2028, but earlier this month, a senior Toyota executive suggested it’ll be only a “couple of years from now”.

“[It] will be a vehicle which will be charging in 10 minutes, giving a range of 1200 km and life expectancy will be very good,” head of Toyota India’s distributor, Vikram Gulati, said to media at the Vibrant Gujarat Global Summit.

The electric Toyota bZ4X will arrive in Australia in February 2024. Photo: Toyota Australia.

In 2020, Volkswagen made similar claims and announced “huge progress” on batteries with 50 per cent more energy density, up to 1000 km of range, and recharge times to 80 per cent in 15 minutes. And the first test results, released last week, are promising.

“Depending on the model, an electric car could drive more than 500,000 kilometres without any noticeable loss of range,” VW found.

To put these figures in perspective, the best-selling car in Canberra last year – the Tesla Model Y – has a claimed range of 533 km and a fast charge (350 kW) to 80 per cent in 30 minutes.

So what is a solid-state battery? And is it the answer to the world’s EV problems?

A technician opening up the battery under the floor of a Tesla Model 3 in the EV workshop at CIT Fyshwick. Photo: James Coleman.

Alexey Glushenkov is an associate professor at the Australian National University (ANU) Research School of Chemistry. He says the tech still uses lithium-ion as the key ingredient, but as the name suggests, now contained in a solid medium.

“EV batteries are large systems that consist of several thousands of individual lithium-ion cells,” he explains.

“Each of these cells contains two electrodes and a lithium-ion containing liquid between them called electrolyte. In solid-state batteries, this liquid component of a cell will be replaced by a solid component (solid electrolyte).”

Liquids can leak, and in the case of lithium-ion liquid electrolytes, catch fire. Solid electrolytes “drastically” reduce this risk.

Studies have shown EVs can lose up to 30 per cent of their range in freezing temperatures because the ions flow through the liquid electrolyte slower when it’s cold. This effect is far less pronounced when the electrolyte is a solid.

And the cells are structurally more stable, so they can be smaller and lighter while storing the same amount of power.

In summary, Professor Glushenkov says we can expect “notable improvement in safety and EV driving range” from solid-state batteries.

Michael Faraday discovered two solid electrolytes in the 1800s, and they’re already used in things like heart pacemakers and RFID tags. So, what’s the hold-up?

Well, there are some … issues.

“There are ongoing technical challenges with solid-state batteries,” Glushenkov says.

“For example, solid electrolytes may develop cracks during cycling, and there is a difficulty creating a consistently good interface between solid electrolyte and electrode materials.”

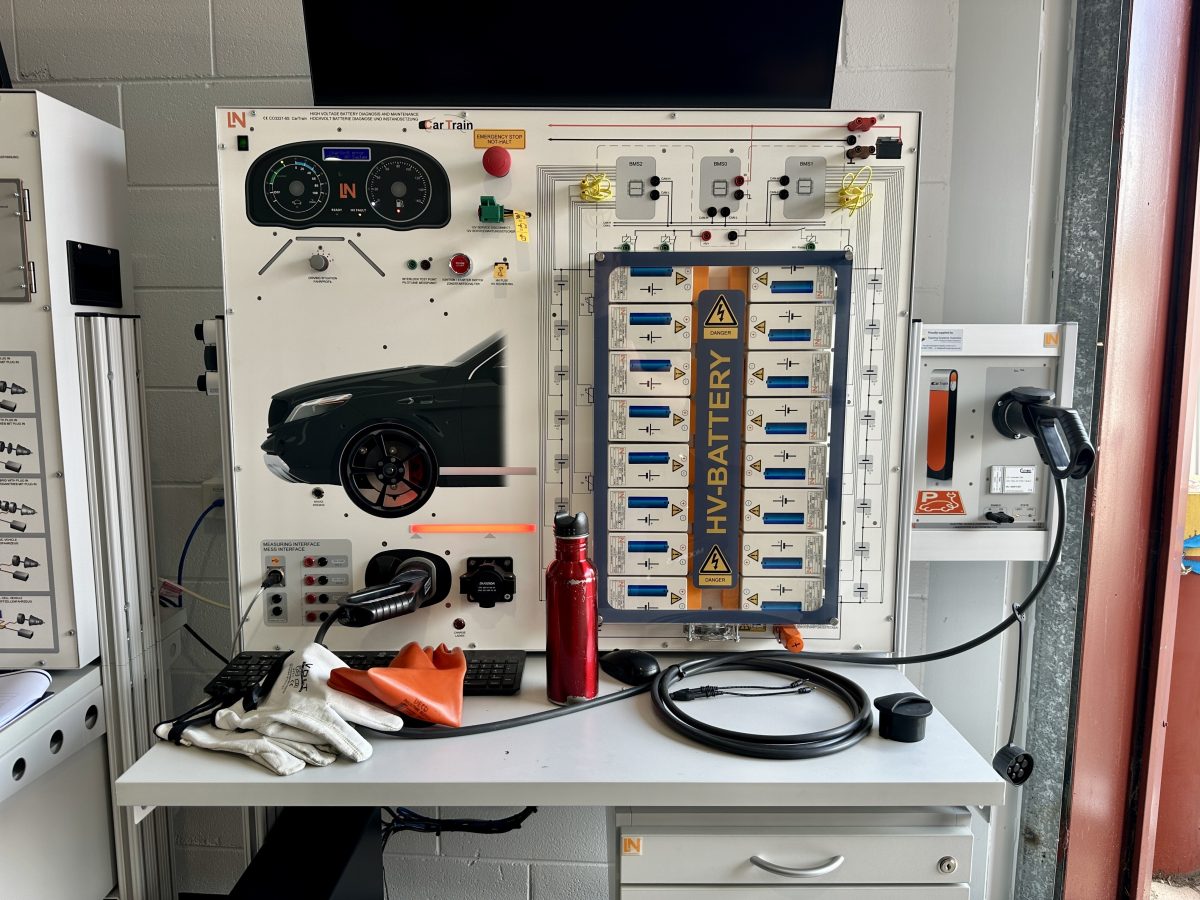

An EV simulator at CIT’s EV workshop. Photo: James Coleman.

In other words, it’s a must to ensure good contact between the electrodes and the solid electrolyte sandwiched in between.

“I would be careful about game-changer comments, but there will be improvements,” he says.

Another technology that swaps out lithium altogether for the far more ubiquitous sodium is also in development. But as it stands, sodium-ion batteries degrade too fast and can only store about 60 per cent of the energy of an equivalent lithium-ion battery.

For now, Toyota’s first all-electric model, the bZ4X SUV, will arrive in Australia next month with some last-minute “battery performance” improvements.

These include a water-based battery-heating system to reduce charge times by between 10 and 80 per cent in cold weather. To save power, the cabin can also be warmed up with a “radiant heater” fitted where the glove box would be. This debuted on the Lexus RZ last year.

Original Article published by James Coleman on Riotact.