Lawmakers advance proposals to let police forces across the EU link their photo databases, which Matt Burgess* says include millions of pictures of people’s faces.

For the past 15 years, police forces searching for criminals in Europe have been able to share fingerprints, DNA data, and details of vehicle owners with each other.

For the past 15 years, police forces searching for criminals in Europe have been able to share fingerprints, DNA data, and details of vehicle owners with each other.

If officials in France suspect someone they are looking for is in Spain, they can ask Spanish authorities to check fingerprints against their database.

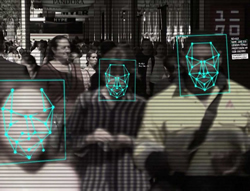

Now European lawmakers are set to include millions of photos of people’s faces in this system—and allow facial recognition to be used on an unprecedented scale.

The expansion of facial recognition across Europe is included in wider plans to “modernize” policing across the continent, and it comes under the Prüm II data-sharing proposals.

The details were first announced in December, but criticism from European data regulators has gotten louder in recent weeks, as the full impact of the plans have been understood.

“What you are creating is the most extensive biometric surveillance infrastructure that I think we will ever have seen in the world,” says Ella Jakubowska, a policy adviser at the civil rights NGO European Digital Rights (EDRi).

Documents obtained by EDRi under freedom of information laws and shared with WIRED reveal how nations pushed for facial recognition to be included in the international policing agreement.

The first iteration of Prüm was signed by seven European countries—Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Austria—back in 2005 and allows nations to share data to tackle international crime.

Since Prüm was introduced, take-up by Europe’s 27 countries has been mixed.

Prüm II plans to significantly expand the amount of information that can be shared, potentially including photos and information from driving licenses.

The proposals from the European Commission also say police will have greater “automated” access to information that’s shared.

Lawmakers say this means police across Europe will be able to cooperate closely, and the European law enforcement agency Europol will have a “stronger role.”

The inclusion of facial images and the ability to run facial recognition algorithms against them are among the biggest planned changes in Prüm II.

Facial recognition technology has faced significant pushback in recent years as police forces have increasingly adopted it, and it has misidentified people and derailed lives.

Dozens of cities in the US have gone as far as banning police forces from using the technology.

The EU is debating a ban on the police use of facial recognition in public places as part of its AI Act.

However, Prüm II allows the use of retrospective facial recognition.

This means police forces can compare still images from CCTV cameras, photos from social media, or those on a victim’s phone against mug shots held on a police database.

The technology is different from live facial recognition systems, which are often connected to cameras in public spaces; these have faced the most criticism.

The European proposals allow a nation to compare a photo against the databases of other countries and find out if there are matches—essentially creating one of the largest facial recognition systems in existence.

One document obtained by EDRi says the number of potential matches could range from between 10 and 100 faces, although this figure needs to be finalized by politicians.

A European Commission spokesperson says that a human will review the potential matches and decide if any of them are correct, before any further action is taken.

“In a significant number of cases, a facial image of a suspect is available,” France’s interior minister said in the documents.

It claimed to have solved burglary and child sexual abuse cases using its facial recognition system.

The Prüm II documents, dated from April 2021, when the plans were first being discussed, show the huge number of face photos that countries hold.

Hungary has 30 million photos, Italy 17 million, France 6 million, and Germany 5.5 million, the documents show.

These images can include suspects, those convicted of crimes, asylum seekers, and “unidentified dead bodies,” and they come from multiple sources in each country.

Jakubowska says that while criticism of facial recognition systems has mostly focused on real-time systems, those that identify people at a later date are still problematic.

“When you are applying facial recognition to footage or images retrospectively, sometimes the harms can be even greater, because of the capacity to look back at, say, a protest from three years ago, or to see who I met five years ago, because I’m now a political opponent,” she says.

“Only facial images of suspects or convicted criminals can be exchanged,” the European Commission spokesperson says, citing a guide on how the system will work.

“There will be no matching of facial images to the general population.”

Pictures of people’s faces shouldn’t be combined in one giant central database, the official proposal says, but police forces will be linked together through a “central router.”

This router won’t store any data, the European Commission spokesperson says, adding that it will “only act as a message broker” between nations.

This decentralized approach makes Prüm II more straightforward: Police wanting to compare fingerprints under the current system must connect to other police forces individually.

Under the new infrastructure, countries only need one connection to the central router and it will be easier to “add additional data categories to the system,” the documents obtained by EDRi say.

The European data protection supervisor (EDPS), who oversees how EU bodies use data under GDPR, has criticized the planned expansion of Prüm, which could take several years.

“Automated searching of facial images is not limited only to serious crimes but could be carried out for the prevention, detection, and investigation of any criminal offenses, even a petty one,” Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the EDPS, said in early March.

Wiewiórowski said more safeguards should be written into the proposals to make sure people’s privacy rights are protected.

The European Commission spokesperson says the body has taken “good note” of the EDPS opinion and the thoughts will be taken into account as the European Parliament and Council discuss the legislation.

During the development of the plans, Slovenia has been one key country pushing for the expansion—including asking for people’s driving license data to be included.

Domen Savič, the CEO of Slovenian digital rights group Državljan D, says there are significant concerns about the differences between police databases and who is included.

“I haven’t heard enough to be convinced that all of this data gathered by individual police forces is sanitized in the same way,” Savič says.

Police databases are often poorly put together.

In July 2021, police in the Netherlands deleted 218,000 photos it wrongly included in its facial recognition database.

In the UK, more than a thousand young Black men were removed from a “gangs database” in February 2021.

“You could have databases that have completely different backgrounds in terms of how this data was collected, where it was sourced, how it was exchanged, and who approved what,” Savič says.

Slovenia has already faced similar problems.

“And this could lead to misidentification.”

One of the biggest problems for Jakubowska is how Prüm II could normalize the use of facial recognition by police forces across Europe.

“What really concerns us is how much this Prüm II proposal could incentivize the creation of facial image databases and the application of algorithms to these databases to perform facial recognition,” she says.

The EU will pay for the cost of connecting databases to Prüm II, the proposal says, and this includes the cost of creating new national facial images databases.

Sixty years after being invented, facial recognition is still just getting started.

*Matt Burgess is a senior writer at WIRED focused on information security, privacy, and data regulation in Europe.

He can be contacted at [email protected].

This article first appeared at wired.co.uk.