According to James Purtill* Australian organisations are quietly paying hackers millions in a ‘tsunami of cyber crime’.

It’s an open secret within the tight-lipped world of cybersecurity.

It’s an open secret within the tight-lipped world of cybersecurity.

For years, Australian organisations have been quietly paying millions in ransoms to hackers who have stolen or encrypted their data.

This money has gone to criminal organisations and encouraged further attacks, creating a vicious cycle.

Now experts say Australia and the rest of the world is facing a “tsunami of cyber crime”.

There has been a 60 per cent increase in ransomware attacks against Australian entities in the past year, according to the government’s cyber security agency, the ACSC.

Just in the past six months alone, the frequency of attacks and the size of ransoms being demanded has increased significantly, said Michael Sentonas, chief technology officer of Crowdstrike, one of the largest cybersecurity companies in the world.

But this message is not being heard by Australian organisations, many of which remain complacent about the threat, he said.

“I still speak to a lot of Australian organisations that say, ‘Why would somebody attack us?’” Mr Sentonas said.

“There’s a little bit of that mentality in Australia.”

So how many organisations have been hit by ransomware, and why is the problem getting worse?

Millions paid to ransomware gangs every year

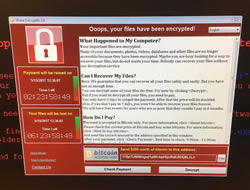

In ransomware attacks, criminals infiltrate an organisation’s computer systems with the aim of stealing, encrypting or otherwise locking up data.

The attackers then demand a ransom payment in return for the stolen data or a copy of the decryption keys.

Because it looks bad and harms their reputation, most organisations do not say when they’ve been hacked and had to pay a ransom.

As a result, there’s often little detail around both the frequency of attacks, the size of the ransom being demanded, and whether it was paid.

A report published this week by the Cyber Security Cooperative Research Centre (CSCRC ) estimated that “cyber crime” has cost the global economy US$1 trillion.

In Australia, this includes a string of ransomware attacks affecting Australian companies in 2020 and 2021, including :

- February and May 2020 – Two attacks in a few months against logistics company Toll Holdings

- March 2021 – An attack against Nine Entertainment that left the company struggling to televise news bulletins and produce newspapers

- June 2021– An attack against JBS Foods, the world’s largest meat supplier, which affected 47 facilities in Australia

The impact of these attacks on JBS, Nine or Toll Group has been “in the realm of catastrophic” for these businesses, Australian Signals Directors (ASD) director-general Rachel Noble told a Senate committee in June.

But they’re relatively small with what the ASD fears may be on the horizon.

Ms Noble quoted a study that estimated a single significant cyber attack against Australia could cost $30 billion and 160,000 or more jobs.

“The threat environment is definitely deteriorating,” she said.

‘It’s a perfect business model’

To get a picture of unpublicised cyber crime in Australia, Crowdstrike surveyed 200 senior IT decision-makers and security professionals across Australia’s major industry sectors.

They found that two thirds of the Australian organisations surveyed had suffered a ransomware attack in the 12-month period to November 2020.

Of those that had been attacked, one-third — or 44 Australian organisations — had paid the ransom.

The average ransom amount was $1.25 million, the survey found.

That’s a rough total of at least $55 million in ransom payments.

If the survey was repeated for the past 12 months, Mr Sentonas said it would show a sizable increase in the proportion of Australian organisations that have suffered attacks.

“It would be a healthy amount larger than what we reported last time,” he said.

The increase in ransomware attacks globally over the past six months has been well documented.

But an attack this month eclipsed them all: hackers infiltrated the global IT-management and security company Kaseya, encrypted sensitive data, and demanded US$70 million.

More than 1500 companies around the world using Kaseya services were affected, including at least five IT services companies in Australia.

Kaseya hasn’t yet paid the ransom and the hackers are now asking for a measly US$50 million.

These successes have encouraged more criminal gangs to mount attacks of their own, Mr Sentonas said.

“There’s so much money being made. That’s the reality of it.”

“And at the end of the day we’re not seeing the adversaries get caught and get prosecuted.

“For them, it’s a perfect business model,” he said.

Ransomware industry growing specialised, sophisticated

In fact, the ransomware business model has become so sophisticated that some hacking groups are specialising in developing and selling the technology that other groups use to mount attacks.

In other words, hacking groups have their own IT services industry.

“You don’t need to be an expert in creating and developing ransomware anymore, you just need to have the appetite to carry out a crime and a little bit of money,” Mr Sentonas said.

The recent hack of the US division of the chemical distribution company Brenntag and the US fuel supplier Colonial Pipeline were both widely reported as the work of a hacking group called DarkSide.

But Mr Sentonas said DarkSide actually made the platform used to mount the attack and was not necessarily the attacker.

“It may not be the creators of a particular platform that are the ones behind the attack,” he said.

“A lot of the people that are behind the attacks could be anywhere.

“The way that the infrastructure is built, it could be someone down the road from your house.”

Many of the prominent hacking groups, however, are based in either Russia or Eastern Europe, where it is harder for them to be prosecuted.

On Friday last week, US President Joe Biden urged Russian President Vladimir Putin to take action against the ransomware group REvil, responsible for the Kaseya and the JBS Foods hacks.

When asked by a reporter later if he would take down the group’s servers if Mr Putin did not, the president replied “yes”.

Days later, REvil’s sites on the dark web suddenly disappeared. It’s unclear who made that happen.

An epidemic of connectivity and standardisation

But the proliferation of hacking groups is not the only reason for the increase in ransomware attacks, says Sergei Shevchenko, chief technical officer of the cybersecurity company Prevasio.

It’s also due to long-term trends within the IT industry itself, he says.

Companies have gone from managing IT in-house to outsourcing this to IT specialists, who may themselves outsource other aspects of their business to specialist companies.

As a result, when a company far up this chain of outsourcing is compromised, hundreds or even thousands of companies “down the chain” are affected too.

This is exactly what happened with the Kaseya hack; an attack against a company in Dublin led to the closure of kindergartens in New Zealand and grocery stores in Sweden.

When everything is connected and standardised, everything is vulnerable.

Mr Schevchenko compares the situation to disease tearing through a monoculture crop.

“In my personal view, the biggest problem is that most victims are using the Windows operating system,” he said.

“So long as there’s a culture of using one operating system, an epidemic will create havoc across that monoculture.”

“The solution to that is a cultural shift into multiple operating systems.”

‘Naming and shaming’ businesses who pay ransoms won’t work

Despite the string of high-profile ransomware attacks, attitudes to cyber security in Australia are “not changing fast enough”, Mr Sentonas said.

Organisations regularly ask him why they would be attacked.

He typically responds: “If you don’t have anything of value, why are you in business?””

“It’s very common when you see an organisation that’s been breached, when they make their first public statement that will say that it was a highly sophisticated attack by a very sophisticated adversary.

“And in most cases, it’s not a sophisticated adversary. And it’s not a sophisticated attack.

“They found it very, very easy to get in. That’s the reality of what we see.”

Rachael Falk from the Cyber Security CRC (CSCRC) agreed, saying many Australian businesses are still “woefully under prepared”.

Her organisation is urging the federal government to develop a mandatory reporting regime for cyber attacks. Labor has also called for such a regime.

Mr Shevchenko said mandatory reporting was “absolutely vital”.

“We will definitely lose this game with the attackers if we don’t enforce reporting.”

But reporting should not be to “name and shame” companies that pay ransoms, as those that do often have little other choice, he said.

Mr Sentonas said organisations that find themselves the victims of ransomware attacks are under “an amazing amount of pressure” to resume operations as quickly as possible.

“Sit in the shoes of the customer that’s trying to work out how to how to get their network up and running.

“The pressure that they’re under is immense.

“And unfortunately, sometimes they do have to make that decision to say this outage is going to cost me ‘x’ and I can recover by paying ‘y’.

“And then they make that decision. They know full well what they’re doing.

“They know that they’re fuelling crime, but it’s a simple business decision.”

The ACSC advises against paying a ransom request.

“Paying a ransom may embolden actors to target additional individuals and organisations, encourage other criminal actors to engage in distribution of ransomware, and/or fund illicit activities,” a spokesperson said.

*James Purtill is a technology reporter for triple j Hack.

This article first appeared at abc.net.au.