Gregory Melleuish* says the main difference between American and Australian attitudes in the pandemic is that Australians prefer being protected to asserting their rights to do as they please.

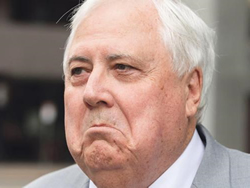

What can we make of Clive Palmer?

What can we make of Clive Palmer?

He has announced that his United Australia Party (UAP) will not contest the West Australian State Election on 13 March.

After a dismal showing in the October 2020 Queensland poll, where does this leave his political prospects?

Given Palmer’s love of publicity stunts and populist policies, one might be tempted to see him as a miniature, Antipodean Donald Trump — but that would be misleading.

Trump was able to garner massive support in segments of the American population, whereas Palmer’s UAP only managed 3.43 per cent of first preference votes in the Lower House at the 2019 Federal Election.

American-style populism does not resonate with large numbers of Australians.

Australian political traditions are quite different to those of the United States, especially in terms of welfare and health provision. Those who seek to take the populist route find it a hard road.

In the 2019 election One Nation and United Australia combined only managed to win 7.76 per cent of the Senate vote.

Given the small base on which the likes of Palmer and One Nation’s Pauline Hanson have to work, one wonders what they now hope to achieve.

The current situation with COVID-19 might provide a clue as to why they have failed to spark a populist surge in Australia.

Palmer’s major contribution to the COVID world was his unsuccessful High Court challenge to force Western Australia to open its borders.

The past 12 months has demonstrated the significance of ‘quarantine culture’ in Australia, a term first coined by cultural historian, John Williams in the 1990s.

The natural instinct of Australians is to close borders against outside threats, be they national or State.

The only partial exception to this rule at the moment is NSW — the one part of Australia that has had a vigorous free trade (or internationalist) political culture since the 19th century.

In late 19th century and early 20th century Australia, writers such as W.G. Spence and magazines like The Bulletin talked about a desire to “protect” Australia against a harsh outside world and, if possible, limit the operation of international finance.

The ideal was an Australia not dependent on the rest of the world.

In this regard, it is also worth recalling that one of the arguments often given for restricting Chinese immigration at the time was they were seen as carrying diseases into Australia.

This was a form of populism — but one quite different to the American version.

It sought to protect Australia and Australians from the outside world, not to assert their right to liberty.

The pandemic seems to have reignited this desire to protect Australians from an outside threat.

The most remarkable aspect of this development has been the way in which this desire for protection has devolved to the State level.

Moves to close borders and institute quite draconian measures to halt the spread of the virus have been generally popular.

Australians, it would seem, are more interested in being protected than they are in asserting their rights to do as they please.

This makes life quite difficult for someone such as Palmer, who has pushed for freedoms and border openings.

No wonder he has decided not to contest the WA State Election. He is not in tune with the popular mood, which has strongly backed Labor Premier, Mark McGowan’s hard border approach.

It is not the time for libertarian populism.

It is difficult to know how long this protectionist attitude will last. One suspects the current situation with China has also fed into it. The mood is one of a threatening world.

From here, two comments are worth making.

The first is political. Prime Minister, Scott Morrison will need to cultivate this threatening mood if he is to succeed at the next Federal Election, which could be held as early as August.

He will need to convince Australians he is the leader who will protect them most effectively. This means going slowly, slowly on things such as opening the international border.

The second is economic. Even in the 1890s, the Australian economy depended on international trade through the sale of wool.

The idea Australia could operate independently of other countries was a fantasy.

The same is true today. The borders will need to re-open and students and tourists let in.

Morrison will have to perform a juggling act. He must appear to be providing protection even as he appreciates protection can go only so far.

In the meantime, the prospects look grim for populists such as Palmer and Hanson.

The Prime Minister and his Coalition have the opportunity to steal many of their supporters.

The pandemic shows that to be successful in Australian politics, leaders need to pose as the protector of the people, not promise more freedom and more openness.

I suspect Morrison understands this very well.

*Gregory Melleuish is Professor, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong. He is a member of the Academic Advisory Board of the Menzies Research Centre.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com