Sarah Frier* and Mark Gurman* say Apple has quietly closed a loophole that allowed app makers to store and share users’ contact data without the consent of the contacts.

Apple Inc. changed its App Store rules last week to limit how developers use information about iPhone owners’ friends and other contacts, quietly closing a loophole that let app makers store and share data without many people’s consent.

Apple Inc. changed its App Store rules last week to limit how developers use information about iPhone owners’ friends and other contacts, quietly closing a loophole that let app makers store and share data without many people’s consent.

The move cracks down on a practice that’s been employed for years.

Developers ask users for access to their phone contacts, then use it for marketing and sometimes share or sell the information — without permission from the other people listed on those digital address books.

On both Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, the world’s largest smartphone operating systems, the tactic is sometimes used to juice growth and make money.

Sharing of friends’ data without their consent is what got Facebook Inc. into so much trouble when one of its outside developers gave information on millions of people to Cambridge Analytica.

Apple has criticised the social network for that lapse and other missteps, while announcing new privacy updates to boost its reputation for safeguarding user data.

The iPhone maker hasn’t drawn as much attention to the recent change to its App Store rules, though.

App Store Review Guidelines now bar developers from making databases of address book information they gather from iPhone users.

Sharing and selling that database with third parties is also now forbidden.

And an app can’t get a user’s contact list, say it’s being used for one thing, and then use it for something else — unless the developer gets consent again.

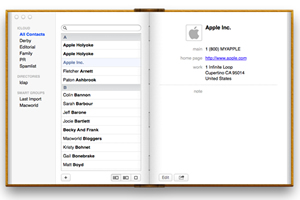

IPhone contact lists contain phone numbers, email addresses and profile photos of family, friends, colleagues and other acquaintances.

When users install apps and then consent, developers get dozens of potential data points on people’s friends.

That’s a trove of information that developers have been able to use, beyond Apple’s control.

Apple’s rules on contact lists have remained relatively consistent for a decade.

Balancing user privacy with the needs of developers has helped the company build a profitable app ecosystem.

“They have a huge ecosystem making money through the developer channels and these apps, and until the developers get better on privacy, Apple is complicit,” said Domingo Guerra, president of Appthority, which advises governments and companies on mobile phone security.

“When someone shares your info as part of their address book, you have no say in it, and you have no knowledge of it.”

While Apple is acting now, the company can’t go back and retrieve the data that may have been shared so far.

After giving permission to a developer, an iPhone user can go into their settings and turn off apps’ contacts permissions.

That turns off the data faucet, but doesn’t return information already gathered.

The Google app store works a similar way.

The difference is that Google mostly keeps quiet about how it uses people’s data for advertising, while Apple often talks about not collecting user information or building profiles of them.

Last week, Apple banned apps from contacting people using information collected via a user’s contacts or photos “except at the explicit initiative of that user on an individualised basis.”

Developers must also provide users with a clear description of how the message will appear to the recipient before sending it.

In early 2017, some iPhone users began getting texts from an app they’d never heard of before.

“A friend added you on ChitChat,” the messages said.

“Tap here to get it.”

ChitChat was built by Swipe Labs, a social product design studio that was using contact list access to market its new messaging service to users’ friends.

In effect, digital cold-calling on steroids.

People complained on Twitter, where venture capitalist Chris Sacca called it “the herpes of contact lists.”

Marwan Roushdy, CEO of Swipe Labs, apologised, calling the tactic a “half-baked growth feature.”

In 2013, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sued social-networking app Path over collecting address book information from iPhones and Android phones without user consent.

Path settled and committed to not misleading users in the future.

Apple CEO, Tim Cook met with Path’s CEO to chastise him for the practice.

While Apple and Google have taken steps to improve app permissions, when things go awry, regulators tend to put the onus on the apps, not the operating systems.

In 2013, the FTC settled with a flashlight app on Android phones for collecting location information and selling it to advertising networks without consumers knowing.

Facebook has stressed that the practice of developers sharing users’ friends’ data was against its rules.

The social-media giant banned the developer who shared this information with Cambridge Analytica.

And it made the political consulting firm sign an agreement confirming it had deleted the data back in 2015.

In March, The New York Times and other outlets reported the information hadn’t been deleted.

The episode started a new global discussion about privacy, with European and some US lawmakers arguing consumers should dictate where their data flows, not giant tech companies.

On the social network, users make their own profiles, while smartphone address books contain digital dossiers that people make about other people.

There may be hundreds of versions of people’s contact information that they have no control over.

The same person might be “Dad” on one phone and “Craigslist Couch Guy” on another.

The woman who bought his couch years ago may still be inadvertently sharing his address with the game she plays on her iPhone every morning.

* Sarah Frier is tech reporter for Bloomberg who tweets at @sarahfrier. Mark Gurman is Apple and consumer tech news reporter at Bloomberg. He tweets at @markgurman.

This article first appeared at www.bloomberg.com.