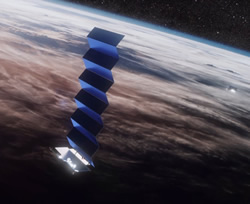

Isobel Asher Hamilton* says astronomers say their observations of space are being affected and their science threatened by Elon Musk’s Starlink project.

An illustration of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet constellation in orbit around Earth. Image: SpaceX

SpaceX, Elon Musk’s powerhouse of a space exploration company, could be on course to seriously compromise humanity’s study of outer space.

Among its many rocket launches and plans to colonise Mars, SpaceX has a more Earthling-focused project.

Its Starlink project aims to put up to 42,000 satellites into orbit around the Earth, where they would beam down data providing internet to remote parts of the globe.

SpaceX has been busily launching the satellites in chunks, flying 60 into orbit at a time.

The company currently has 180 satellites in orbit and plans to launch new batches every two weeks or so for the rest of 2020.

The sudden proliferation of Starlink satellites has been met with anger by professional and amateur astronomers, as Starlink satellites have been leaving bright streaks across astronomical images.

SpaceX responded with a solution: Make the next batch of satellites dark.

On 6 January, the company launched 60 satellites coated in an “experimental darkening treatment”.

Elon Musk promised in a tweet that Starlink wouldn’t “inhibit new discoveries or change the character of the night sky”.

His assurances haven’t assuaged the community’s fears.

Experts told Business Insider that painting satellites dark is not only an extremely difficult feat of engineering, but it also does not address some of the most pressing concerns of the astronomical community.

Giorgio Savini, Director of the University College London Observatory, said: “Deciding to paint a satellite black is not something you do lightly.”

One of the biggest problems with painting a satellite dark is heat regulation.

Dark paint absorbs the heat of the sun, causing the satellite to heat up significantly and then cool when it goes into the Earth’s shadow.

“Temperatures varying in space is something you don’t want because that means that mechanical structures heat up, they dilate or they contract when they cool down … and things aren’t where they’re supposed to be,” Savini said.

Designing a coat of paint that can withstand the rigors of space without peeling off is also no mean feat.

SpaceX has not said which material it’s using in its coating.

Dark satellites could be worse than bright ones

Even if SpaceX manages to navigate the various engineering problems and launch completely dark satellites, these could come with their own problems.

One of the main ways astronomers look for things like exoplanets is by monitoring the light given out by stars.

When a planet passes in front of a star it blocks the light causing a brief flicker that can be detected and investigated — this is called “occultation”.

The worry is that dark satellites passing in front of stars could mimic this phenomenon.

“We’re going to be wasting an awful lot of time following these up,” said David Clements, an astronomer at Imperial College London.

“[An occultation] might be a real dip because the star might be doing something strange, or it might be one of these satellites, how are we going to tell?”

“We can’t.”

The sheer number of Starlink satellites planned (42,000) is what makes this a pressing threat.

“If we were talking about one or two satellites, I wouldn’t be worrying too much,” said Savini.

The satellites could still play havoc with radioastronomy

A dark coating doesn’t address one of the major problems with the Starlink satellites: They could compromise the subfield of radio astronomy that studies normally invisible wavelengths of light.

Radio telescopes are extremely sensitive devices that detect bursts of radio energy coming from outer space.

They’re generally kept in radio-quiet reserves, with no mobile phone towers for miles and signs telling people to switch off their mobile phones if they approach.

“The prospects for radio astronomy are arguably even worse than for the optical side,” said Clements.

First, to transmit data to provide internet Starlink will have to use a broad range of frequencies, and second, the number of satellites circling the Earth will cover an extremely large area of the Earth’s surface.

“The footprint of these satellites is going to be much, much bigger than ground-based transmitters, making it much harder to establish preserves,” Clements said.

“They are going to be blinding the radio telescopes, possibly quite literally if the signals are going to be strong enough to damage the receivers that we’re working with.”

Astronomers worry this is the beginning of a satellite avalanche

On top of the technical problems surrounding Starlink satellites specifically, the push of commercial companies into space could signal the start of a larger trend.

While Savini doesn’t oppose the use of commercial satellites in space, he worries that a sudden acceleration of launches could end up breaking ground-based astronomy.

“Then that means that astronomy, to progress, needs to launch satellites and we can’t do anything from the ground, and that’s going to be a big slowdown in terms of science,” he added.

“Unfortunately, popular culture sees astronomy as a hobby rather than a science and they forget an enormous portion of physics that we know now is thanks to astronomy.”

To Clements’ mind, the fact that tech billionaires are spearheading these constellations is an even bigger cause for concern.

“As far as SpaceX is concerned, they’re definitely doing the move-fast-and-break-things approach of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, only in this particular instance they’re breaking the sky and they’re breaking chunks of astronomy,” he said.

Despite Musk’s insistence that SpaceX is engaging with astronomers, Clements’ outlook on the channels of communication between SpaceX and the scientific community was bleak.

“It really does knock the confidence of people trying to engage with them to come up with some kind of compromise because you don’t feel you’re being listened to,” Clements said.

* Isobel A. Hamilton is a tech reporter at Business Insider UK. She tweets at @Hamilbug.

This article first appeared at www.businessinsider.com.au.