Ariel Bogle* says people with disabilities face ‘encoded inhospitality’ and numerous other barriers as they try to access the internet.

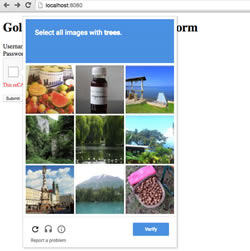

Dr Scott Hollier logged into an online portal recently, and was immediately faced with a familiar yet irritating internet question: “How many of these pictures include buses?”

Dr Scott Hollier logged into an online portal recently, and was immediately faced with a familiar yet irritating internet question: “How many of these pictures include buses?”

CAPTCHA security tests, or the “Completely Automated Public Turing Test, to Tell Computers and Humans Apart”, are not always accessible to people with disabilities — sometimes putting them, ridiculously, in the “robot” category.

“I had two choices,” said Dr Hollier, a digital access specialist who is legally blind.

“I could either not do what I needed to do for my work, or I could ask my 11-year-old son to come figure it out for me.”

These moments of friction or “encoded inhospitality”, as accessibility advocate Chancey Fleet has put it, block non-visual access to everyday digital interactions.

She also calls them “dark patterns” — a term popularised by British user-experience consultant Harry Brignull, which describes online techniques that manipulate users.

A completely fake online countdown, for example.

Ms Fleet said that while most conversations about dark patterns focus on design choices that nudge, deceive and distract, the concept should extend to “inhospitable design features arising from inattention, neglect and false assumptions about the capabilities and desires of disabled people”.

For people who are blind or vision impaired, such roadblocks can “come and go without documentation, explanation or apology”, she wrote in an email.

‘Dark patterns’ everywhere

Like asking your son to help you get past CAPTCHA, the onus is often on people who have a disability to use workarounds when they encounter “dark patterns” online.

If not, accounts are not set up, purchases are not made and full participation in the online economy and conversation is elided.

Think of navigating a football ticket purchase with a screen reader that converts text to audio or braille, only to have the web page time out because you took longer than the allotted eight minutes.

Dr Hollier has taken on CAPTCHA in particular, writing advice for the World Wide Web Consortium that offers alternative methods for website designers that are less exclusionary.

“The oldest CAPTCHA is the one with the squiggly letters, which are almost impossible to read under the best of circumstances,” Dr Hollier said.

“And understandably, people who are blind can’t do those ones either.”

“And the audio CAPTCHAs are terrible as well.”

Web accessibility consultant Mark Muscat said webform instructions can also be problematic.

It’s also just bad for business.

“If people can’t use a website within … 30 seconds, they’re going to go look somewhere else,” he said.

While many online services have accessibility features, they’re not always implemented by default — another dark pattern, in Ms Fleet’s view.

Take Twitter, which offers the ability to add image descriptions so that they will be included by screen readers.

But the option is buried in its settings and not turned on by default.

“This dark pattern profoundly limits the ability of blind people to perceive and engage with memes, infographics, and photos that express identity, affect and aesthetic experience,” Ms Fleet said.

Slowly, solutions do emerge.

Google, for example, has introduced ReCAPTCHA, which attempts to determine human versus bot based on the user’s recent online interactions rather than making them click on pictures.

Who makes the rules?

Dr Hollier looks at accessibility from two perspectives: Can people with disabilities access assistive technologies such as screen readers on the devices of their choice, and is online content accessible?

“What’s been exciting in recent years is that whether we’re talking Windows or iPhone, iPad or Android or a Mac, accessibility features are largely built in,” he said.

Ensuring content is accessible across desktops, laptops, tablets and mobile devices, however, remains a challenge.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 (WCAG 2.1) is an international standard, with recommendations that Dr Hollier said would address many of the digital “dark patterns”.

He suggested moving Australian websites and apps to WCAG 2.1 should be a priority.

Another challenge raised by Dr Hollier is that Australia’s Disability Discrimination Act, which first passed in 1992, is not explicit enough about technological accessibility.

Dr Ben Gauntlett, Australia’s Disability Discrimination Commissioner, acknowledged the law was drafted at a time when most computer technologies were not prevalent.

“There is a critical need for us to assess whether the Disability Discrimination Act is fit for purpose in relation to new technology,” he said.

“All service providers in Australia need to realise that there are a lot of people from a diverse range of backgrounds who use their services.”

What to do next

To fight against “dark patterns” that stymy people with disabilities, advocates see a few ways forward.

Ms Fleet suggested that accessibility errors could be displayed to users and developers just like spelling and grammar mistakes.

“Let’s assume that users would rather know they’re creating a problem, rather than ‘save’ them a moment on the assumption that no one will need their work to be accessible,” she said.

“Treat accessibility errors like fire code violations: correct them every time so that the things we collectively build are safe for everyone.”

Mr Muscat said web accessibility should be a part of any project from the ground up.

Dr Hollier also wants more people with disabilities involved in user experience testing, and Ms Fleet suggested dark patterns arise because people who use accessibility tools are not on development teams or hired to test technology and new software before it goes live.

She believes that employing people with the lived experience of a disability can help, but also advocates “fierce and sustained allyship to hold companies accountable to bake accessibility into ALL products”.

“Tech culture — from platforms to procurement to education — must shift away from focusing on accessibility when a person with a disability presents a need, and shift toward treating accessibility as a consistently required part of every product,” she said.

Twitter was contacted for comment.

* Ariel Bogle is the online technology reporter in the ABC RN science unit. She tweets at @arielbogle.

This article first appeared at www.abc.net.au.