By Sean Gallagher.

Imagine if someone could scan every image on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, then instantly determine where each was taken.

Imagine if someone could scan every image on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, then instantly determine where each was taken.

The ability to combine this location data with information about who appears in those photos — and any social media contacts tied to them — would make it possible for Government Agencies to quickly track terrorist groups posting propaganda photos.

(And, really, just about anyone else.)

That’s precisely the goal of Finder, a research program of the US Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency (IARPA), the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s dedicated research organisation.

For many photos taken with smartphones (and with some consumer cameras), geolocation information is saved with the image by default.

The location is stored in the Exif (Exchangable Image File Format) data of the photo itself unless geolocation services are turned off.

If you have used Apple’s iCloud photo store or Google Photos, you’ve probably created a rich map of your pattern of life through geotagged metadata.

However, this location data is pruned off for privacy reasons when images are uploaded to some social media services, and privacy-conscious photographers (particularly those concerned about potential drone strikes) will purposely disable geotagging on their devices and social media accounts.

That’s a problem for intelligence analysts, since the work of trying to identify a photo’s location without geolocation metadata can be “extremely time-consuming and labor-intensive,” as IARPA’s description of the Finder program notes.

Past research projects have tried to estimate the location where images were taken, learning from large existing sets of geotagged photos.

Such research has resulted in systems like Google’s PlaNet — a neural network-based system trained on 126 million images with Exif geolocation tags.

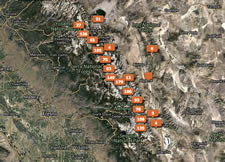

But this sort of system falls apart in places where there haven’t been many photos taken with geolocation turned on — places tourists tend not to wander to, like Eastern Syria.

The Finder program seeks to fill in the gaps in photo and video geolocation by developing technologies that build on analysts’ own geolocation skills, taking in images from diverse, publicly available sources to identify elements of terrain or the visible skyline.

In addition to photos, the system will pull its imagery from sources such as commercial satellite and orthogonal imagery.

The goal of the program’s contractors — Applied Research Associates, BAE Systems, Leidos (the company formerly known as Science Applications Incorporated), and Object Video — is a system that can identify the location of photos or video “in any outdoor terrestrial location.”

Finder is but one of several image processing projects under way at IARPA.

Another, called Aladdin Video, seeks to extract intelligence information from social media video clips by tagging them with metadata about their content.

Another, called Deep Intermodal Video Analytics (DIVA), is focused on detecting “activities” within videos, such as people acting in a manner that could be defined as “dangerous” or “suspicious” — making it possible to monitor huge volumes of surveillance video simultaneously.

* Sean Gallagher is Ars Technica’s IT and National Security Editor. He tweets at @thepacketrat.

This article first appeared at arstechnica.com.