Reviewed by Robert Goodman.

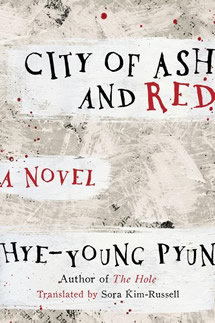

By Hwe-Young Pyun, Translated by Sora Kim-Russell, Skyhorse Publishing.

There are so many interesting novels coming out of Korea at the moment – challenging established Western tropes across a range of genres. Just this year there has been the psychothriller The Good Son by Jeong Yu-jeong, the anti-hero crime drama The Plotters by Un-su Kim and At Dusk, another masterpiece of introspection and history from Hwang Sok Yong. Into this mix comes what could be described as dystopian existentialist horror –The City of Ash and Red by Hwe-Young Pyun. A kafkaesque descent into a nightmare world that, in some strange way, has echoes of all of the books and authors previously mentioned. As with many of those books, also, this has been translated by Sora Kim Russell.

There are so many interesting novels coming out of Korea at the moment – challenging established Western tropes across a range of genres. Just this year there has been the psychothriller The Good Son by Jeong Yu-jeong, the anti-hero crime drama The Plotters by Un-su Kim and At Dusk, another masterpiece of introspection and history from Hwang Sok Yong. Into this mix comes what could be described as dystopian existentialist horror –The City of Ash and Red by Hwe-Young Pyun. A kafkaesque descent into a nightmare world that, in some strange way, has echoes of all of the books and authors previously mentioned. As with many of those books, also, this has been translated by Sora Kim Russell.

An unnamed man is taken out of the immigration queue at the airport. He is sick and may well be infected with a virus that is potentially the indicator of a pandemic. The man has come to Country Y to work, transferred by his company. But when he is taken to his apartment, on an island groaning under the weight of uncollected garbage and blanketed in a fog of disinfectant, it turns out that perhaps there may not be a job for him after all. Before he can do much about that his whole apartment block is put under quarantine. From there things go from bad to worse.

Pyun creates a nightmare-scape in an almost post-apocalyptic landscape. But the apocalypse, if there ever was one, never quite arrives. Instead this is one man’s descent from office worker, to vagrant living in a garbage dump, to a literal and figurative descent even lower. As in Kafka, the rules are never quite clear and just as the man works them out he finds he is on the wrong side of them. And there may be a story of redemption here except that when things look like they might be turning around they take an even darker turn.

City of Ash and Red is not an easy read. The protagonist, despite his plight is not particularly likeable, in fact in some respects he is completely unlikeable. And the rat-infested world in which he finds himself is nasty and brutish. As noted, these aspects have emerged in other recent Korean fiction. The Good Son was also hinged around an extremely unlikeable main character. Hwang Sok-Yong’s Familiar Things, while much more optimistic and heart-felt, was set in and around a garbage dump where a young boy grows up as a “picker” and Un-Su Kim never tries to sugar coat the darkness at the heart of The Plotters. But Pyun, with deadpan language and a nightmarish atmosphere, heightens these aspects to the point where parts recall the bleakness and nihilism of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

While Pyun toys with an apocalyptic scenario she never quite gets there, managing to twist the narrative into something else entirely by the book’s shocking, but in some ways inevitable, conclusion.

This and 300 more reviews can be found at Pile By the Bed.

![]()