Saurav Dutta, Harjinder Singh and Nigar Sultana* outline the dangers of four common debt traps: payday loans, consumer leases, blackmail securities and credit ‘management’.

From Shakespeare’s Shylock to Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge to HBO’s Tony Soprano, characters who lend out money at exorbitant interest rates are unsavoury.

From Shakespeare’s Shylock to Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge to HBO’s Tony Soprano, characters who lend out money at exorbitant interest rates are unsavoury.

So, what should we think of businesses that deliberately target the poorest and most vulnerable for corporate profits?

There has been significant growth in the unregulated small-loan market, aimed at people likely to be in financial stress.

Concern about the problem led to an Australian Senate Select Committee inquiry into financial products targeted at people at risk of financial hardship.

It found plenty to report on, with businesses structuring their lending practices to exploit loopholes in consumer credit laws and to avoid regulation.

Charging fees instead of interest is one example.

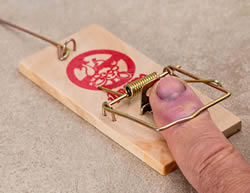

Below is a snapshot of four common lending practices identified in the inquiry’s final report.

The practices may be legal, but they all carry the high potential to make your financial situation worse and ensnare you in a debt trap from which it is hard to escape.

- The payday loan

Payday loans are advertised as short-term loans to tide you over until your next payday.

They can be up to A$2,000.

The payback time is between 16 days and 12 months.

Lenders are not allowed to charge interest but can charge fees, including an establishment fee of up to 20 per cent and a monthly fee of up to 4 per cent of the amount loaned.

If you don’t pay back the money in time, the costs escalate with default fees.

Most payday loans are “small amount credit contracts” (SACC), with three companies — Cash Converters, Money3 and Nimble — dominating the market.

In 2016, Cash Converters had to refund $10.8 million to customers for failing to make reasonable inquiries into their income and expenses.

In 2018, it settled a class action for $16.4 million for having charged customers an effective annual interest rate of more than 400 per cent on one-month loans.

But it is not necessarily the worst offender.

The Senate inquiry’s report singles out one company, Cigno Loans (previously Teleloans), for appearing “to have structured its operations specifically to avoid regulation”, so it can charge fees that exceed the legal caps.

If you are on a low income and need money for essential goods or services, a better option is the Federal No Interest Loans Scheme (NILS), which provides loans of up to $1,500 for 12 to 18 months with no interest charges or fees.

- The consumer lease

A consumer lease is a contract that lets you rent an item for a period, usually between one and four years.

You make regular rental payments until the term of the lease finishes.

This can be appealing because the regular payments are very low.

But the length of the lease and terms of the contract end up making renting an item a very expensive option.

The Senate inquiry report notes that while consumer leases are subject to responsible lending obligations, unlike SACCs there is no cap on the maximum cost of a lease, and you will invariably pay more than the cost of buying and owning an item outright.

The report refers to a 2015 study by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) involving Centrelink recipients leasing goods.

Half paid more than five times the retail price of the goods.

In one case leasing a clothes dryer for two years effectively cost 884 per cent in interest.

Consumer lease companies disproportionately profit from those on low incomes.

The Senate inquiry heard about the number of leases being paid through Centrepay, the direct debit service for Centrelink recipients.

Thorn Group, owner of Radio Rentals, told the inquiry 52 per cent of its consumer-leasing customers paid via Centrepay.

ASIC’s rent vs buy calculator can help you work out the cost of consumer lease and whether a better option is available.

- The blackmail security

Lenders sometimes earmark a borrower’s asset as a guarantee for the loan.

If the debtor defaults, the lender takes the asset in compensation.

Normally, the asset should be of higher value than the loan amount, to cover the debt if the debtor ever defaults.

However, a lender might choose an asset with a lower value, because it is critical to the borrower’s livelihood.

A car or work tools are two examples.

The intention is to ensure the borrower prioritises repaying the loan over other expenses.

Should you be unable to pay back the loan for some reason, losing an asset critical to earning an income will push you into greater financial hardship.

Because the practice is regarded as coercive, so-called blackmail securities are prohibited on loans lower than $2,000.

The Senate inquiry report notes concern that some lenders appear to circumvent this restriction by lending more than $2,000.

So, think very carefully about the consequences if you can’t repay the loan.

- The credit ‘manager’

If you’re in debt and ended up with a bad credit rating, credit repair services offer help fixing your credit history or managing your debts.

These services may be legitimate businesses or non-profit community services.

But there has been an alarming growth in unregulated debt negotiation and debt management services, charging exorbitant and hidden fees for minimal services.

The fees and contract structures may be deliberately complex to obscure the costs.

According to the Senate inquiry report: “On the evidence provided to the Committee in submissions and public hearings, these services rarely improve a consumer’s financial position.”

“The charges for the debt management services increase their debt, and often consumers are referred to inappropriate remedies which may be expensive and cause lasting damage.”

ASIC recommends seeking help from free services first.

You can find one through its MoneySmart website.

Social obligation

Most people would agree we want a society that protects the most vulnerable.

That includes having laws and regulations to protect the financially vulnerable.

The growth of financial services that target those most at risk of financial hardship suggests Government and industry should take seriously the Senate inquiry’s recommendations.

* Saurav Dutta is Head of the School of Accounting at Curtin University. Harjinder Singh is the Director of Graduate Research within the School of Accounting at Curtin. Nigar Sultana is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Business and Law, Curtin University.

This article first appeared at theconversation.com.