Rob Dozier* meets the youngest person in the US to build a personal nuclear reactor in his home.

Memphis-native Jackson Oswalt is a pretty normal eighth grader in most regards.

Memphis-native Jackson Oswalt is a pretty normal eighth grader in most regards.

He plays tennis and runs cross country. He likes school and hanging out with his friends.

He even plays Fortnite now and again.

But in addition to all that, the 14-year-old also enjoys fiddling with a nuclear reactor that he keeps in his home—one that he built when he was 12.

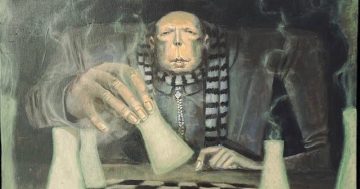

His unusual hobby started couple of years ago, when Oswalt (pictured with his bedside reactor) came across a story about Taylor Wilson, a 14-year-old who built his own nuclear fusion reactor in his garage in Reno, Nevada, in 2008, making him the youngest person to ever achieve nuclear fusion.

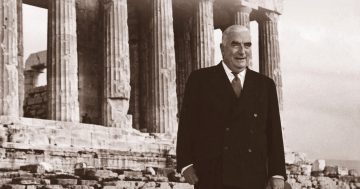

The achievement earned him praise and accolades and even a visit with President Barack Obama.

Wilson, now 24, works as a researcher exploring ways to make nuclear fusion more efficient.

Wilson remained the youngest person to achieve fusion until January 2018, when Oswalt did it at age 12.

Oswalt’s results were verified by members of a forum called Fusor.net that included physicists and hobbyists alike, making him the youngest person to ever build a working nuclear fusion reactor.

And it was Wilson’s story that sent Oswalt, who has bit of a competitive streak, down that rabbit hole, he told me.

“Once I saw that he did it, I thought maybe I could give it a shot,” Oswalt told Motherboard in a phone interview.

First he had to get a primer on nuclear fusion, a process in which atoms are smashed together in order to produce energy. It’s a much safer alternative to the fission process, which involves splitting atoms apart, because unlike in fission—which is used in nuclear power plants to produce energy—there’s no risk of meltdowns and it produces far less radioactive waste.

To achieve fusion, you need to be able to generate heat at 100 million degrees Celsius, which means the process actually uses more energy than it produces.

But scientists are working to change that, without much luck.

Oswalt decided to take on the challenge anyway, starting with research on what it takes to build a nuclear fusion reactor—the parts, what tools he would need, and how long it would take.

Oswalt caught on quickly. While growing up he spent hours building things in his grandfather’s woodshop, which he said made him feel confident enough to take on a nuclear reactor next.

What pushed him though was the opportunity to one-up Wilson and become the youngest person to achieve nuclear fusion.

“It was definitely for the challenge of it. It was always in the back of my head that I wanted to be the youngest,” he said.

Oswalt started with poring over other people’s accounts of how they built their reactors. He then assembled a list of parts he would need, which added up to nearly $10,000, he said.

Fortunately his parents were, while confused, totally on board.

“Because my brain doesn’t work like Jackson’s does, the whole notion of nuclear fusion didn’t register with me,” Chris Oswalt, his dad, who works for an orthopaedics company, told Motherboard.

“But being a parent of someone that was as driven as he was, was really impressive to see.”

At his home in Memphis, Oswalt started spending a good part of his free time working on building the reactor in an old playroom that he converted into his lab.

He cherry-picked lessons from people who had done it before to make his project better, and mainly relied on trial and error, he told me.

Working with electricity at more than 50,000 volts and radioactive material wasn’t enough to make Oswalt sweat. But his parents, concerned about safety, pushed him to consult with anyone that might be able to provide some guidance.

They didn’t have much success finding a nuclear physicist, so they consulted Oswalt’s physics teacher, who was excited to help.

The family also enlisted researchers from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis to tell him how to protect himself from radiation, and a physics professor from Christian Brothers University.

“As a parent, safety was my No. 1 concern,” said his dad. “Jackson was able to become an expert, but we all learned together.”

Other than his parents and circle of collaborators, Oswalt largely kept his work on the reactor to himself.

“For the most part, I didn’t really mention it to my friends,” he said.

“And the close friends I did tell thought I was kidding, to be honest. And some of my teachers didn’t believe me.”

But once they saw that he was serious about the work he was doing, he told me, everyone was impressed and supportive.

Along the way, Oswalt posted updates on his progress on Fusor.net, soliciting advice and pointers.

The site is named for a part of the type of reactor that Oswalt used. It’s where the atoms are fused using an electric field to heat them.

A year after he started, just before his 13th birthday, he reached fusion, and he posted his results on the forum for verification.

After looking them over, Richard Hull, an administrator for Fusor.net and a retired electronics engineer recognised Oswalt as the youngest person to achieve nuclear fusion, possibly in the world.

“You have to jump through the right hoops, and we have to believe you and see what you’ve done,” Hull told Fox News.

For Oswalt, this was only a stepping stone. Despite achieving nuclear fusion in early 2018, he only recently started discussing the accomplishment publicly.

“Jackson is a smart guy and probably under-appreciates that about himself,” said his dad.

He’s onto planning his next reactor using the spherical tokamak method, which traps energy differently than the reactor that he’s already built.

He’s also decided that he wants to pursue nuclear physics as a career because he thinks he’ll be the one to make a fusion reactor that is actually efficient.

“He certainly has a head start,” said his dad.

Oswalt also expressed interest in starting an organisation to help kids like him fund projects like his.

“I realised that certain things that I thought were impossible for someone my age aren’t impossible,” he said.

“Kids make up a large part of the population and some of them have great ideas, and if they can’t make those ideas a reality it’s a waste.”

* Rob Dozier is a US writer and radio producer. He can be contacted at robardzr.contently.com.

This article first appeared at motherboard.vice.com