Nick Huntington-Klein and Elaina Rose* say a study of a military academy reveals how increasing the number of women in groups is a powerful tool for increasing their representation in male-dominated fields.

Over the last several decades, women have made tremendous gains in many professions.

Over the last several decades, women have made tremendous gains in many professions.

But in others progress has lagged.

What is holding women back?

What can be done to help more women enter and achieve parity in male-dominated fields?

There are many possible reasons for the gender gaps.

They include gender biases and “bro culture” that can make male-dominated environments unwelcoming to women.

Another possible explanation is that the gender gap is itself to blame — women don’t get enough support because there aren’t many other women around.

Perhaps women would benefit from simply having more women among their peers.

There is some evidence supporting this.

Studies show that women in undergraduate engineering programs with more female graduate mentors are more likely to continue in the major, and women who are friends with high-performing women are more likely to take advanced science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) courses.

But it may be that women aren’t benefiting from the support, but that women with greater commitment to a field tend to gravitate toward similar women.

This is what economists refer to as the problem of selection bias, which makes it unclear whether the peer group is what causes success.

Another issue is that some studies show that women’s success is actually hampered by having more female peers.

This can happen when women are put in positions where they must compete with one another, so having more women around makes it harder to succeed.

How do we know whether women actually help other women?

Ideally, we would do an experiment where women are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups.

Women in the treatment group would have women peers, and women in the control group would not.

Such opportunities for randomisation are rare, but we found one.

We took a cue from economist David Lyle, who recognised that student cadets at military academies are randomly assigned to peer groups called cadet companies.

This can create a natural experiment for studying peer effects without concern about selection bias.

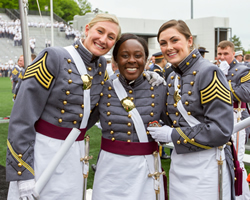

West Point

The US Military Academy at West Point trains cadets to be Army officers, and the program is challenging.

Standards are high and cadets’ performance is closely monitored.

The student body (or Corps of Cadets) is structured as a hierarchy comparable to the Army.

It is divided into four regiments, which are each divided into three battalions, which are each divided into three companies.

We studied the classes of 1981 to 1984, the second through fifth graduating classes that included women.

In those years, cadets had few opportunities to interact with the outside world.

There was no email, internet or mobile phones.

Cadets were isolated within the Academy as well.

They were required to live, eat and participate in activities with their own companies.

Many graduates recall a brutal first year at West Point.

Senior-ranking cadets are charged with instructing more junior cadets in military protocol and disciplining them for infractions.

When women first entered West Point in 1976, there was considerable controversy.

Women were often singled out for particularly harsh treatment, though there was substantial variation across the student body.

With an average of 103 women spread across the Academy each year, compared with 1,146 men, women had little opportunity to interact with other women.

Not surprisingly, women’s attrition rates were about 5 percentage points higher than men’s — a big difference when attrition rates for men are only 8.5 per cent.

Women and peer groups at West Point

We were able to track each cadet’s randomly assigned peer group by gender, and their progression from year to year.

We found that, when another woman was added to a company, it increased the likelihood a woman would progress from year to year by 2.5 per cent.

This means that, on average, an extra two women in a company on top of what it already had would completely erase the female/male progression gap.

Another way to think about the size of the effect is to consider only first-year cadets, who have the worst attrition rates.

Women in first-year groups with only one other woman only had a 55 per cent chance of sticking around for the next year.

But women in the most woman-heavy groups, with six to nine other women, had an 83 per cent chance of continuing to the next year.

One concern is that while the addition of more women helps other women, it may make men less likely to progress.

But, when we compared results for men with results for women, we found no effect of women peers on men, positive or negative.

Beyond West Point of the 1980s

Unlike other studies, the natural randomisation of cadets to companies has made it possible for us to say that there is a substantial benefit to women from having women peers.

But West Point of the 1980s was unusual.

How would these results apply more generally?

Things have changed considerably at the institution in the past 40 years.

These days cadets have more opportunities to interact with friends and family outside and other cadets within the Academy.

The need for support may have changed as the experience has eased.

There are many other reasons that these results may not carry over to a workplace of 2018.

There is greater awareness now of the challenges that women face when they are in a small minority and greater willingness of leaders to mitigate the challenges.

It would be interesting to see what a similar study would show in a corporate workplace.

Until that time, the best evidence is that attending to gender when assigning women to groups can be a powerful tool for increasing the representation of women in male-dominated fields.

* Nick Huntington-Klein is an Assistant Professor of Economics at California State University Fullerton.

Elaina Rose is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Washington.

This article first appeared at hbr.org.