Michelle Gibbings* says trust is an essential element in the day-to-day functioning of our personal and working lives — but how to know when to give it or withhold it?

Do you sit in the camp where people need to earn your trust, or do you automatically trust people when you first meet them?

Do you sit in the camp where people need to earn your trust, or do you automatically trust people when you first meet them?

Trust is fundamental for how we function in our personal and working lives and for effective communities and societies.

If you can’t trust, it’s hard to make decisions.

Trust is an inherent element for relationships, and it assumes the other party will act in a certain way.

Trust can be strengthened or diminished over time based on a person’s actions and how you react or respond in return.

If you’ve ever played a trust game, you’ll know that some people are more trusting than others; research also supports this view.

Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, writing in the Harvard Business Review, suggest that for leaders to build trust there are three core ingredients.

These are positive relationships, good judgment, expertise, and consistency.

Research Professor and author, Brené Brown uses the BRAVING model: Boundaries, Reliability, Accountability, Vault, Integrity, Non-Judgement and Generosity, to outline the elements necessary for trust to flourish.

We are more likely to trust people whom we perceive as like us or familiar.

Our brain very quickly assesses whether it sees someone as a ‘friend’ or ‘foe’.

It sizes them up and decides whether a person is ‘in my tribe’ or ‘outside my tribe’.

The brain then processes the information we receive from that person according to which category we’ve put them in.

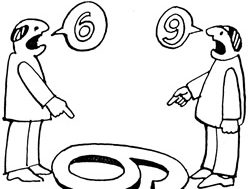

If two people are saying the same thing to us, and one person is considered a ‘foe’ and the other person a ‘friend’, we will interpret what they are saying differently.

It’s like giving someone the benefit of the doubt. We will do that for a friend, but not for a foe.

In the workplace, if you see other people as ‘foe’, you are more likely to misinterpret their intent, which leads to distrust, disagreement, and unproductive competitive behaviour.

Frank Bernieri, of Oregon State University, has found we assess people relatively quickly, without a lot of data.

Upon first meeting someone, we quickly determine whether we trust them or not.

As we do this, we decide whether we like them and see them as with us, or against us, and as part of our tribe or not.

Similarly, Amy Cuddy, in her book Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges suggests that first impressions form as we try to answer two questions.

What are this person’s intentions toward me?

How strong and competent is this person?

In doing this, she says we are judging firstly, how warm and trustworthy the person is, and secondly, whether or not we think they’re capable of enacting their intentions.

Without the ability to trust, it is almost impossible to communicate and cooperate.

Think about it for a moment; if you always assume the person in front of you is a liar, it would be tough to get anything done.

Malcolm Gladwell explores this beautifully in his brilliant book, Talking to Strangers.

For much of the book, he relies on two key elements — our desire to default to truth and how when a person’s behaviour doesn’t match expectations, we quickly judge them as faulty in some way.

The default to truth theory argues that when we communicate with each other, we tend to operate on the default assumption that what the other person is saying is honest.

This makes sense. If you always assumed that people were deceptive and lying to you, cooperation and effective communication would be almost impossible.

However, we don’t believe people when there is a mismatch between what they are saying or doing (or not saying or doing) and how we would expect them to behave given the circumstance.

We are quick to judge. We have expectations, social conventions and assumptions about how people should behave.

This problem is one of the reasons why reading body language and facial expressions can be so fraught with danger.

We often think we are accurate assessors of others. We aren’t. We misinterpret body language and facial expressions all the time.

As Professor of Communication, Timothy Levine states in his research: “When people rely on demeanour to infer deception, accuracy is typically poor and slightly better than chance.”

So, where does that leave us? It means that when we talk with people, we need to listen. Really listen. Listen deeply and with good intent.

We need to drop the judgement and go beyond our initial assumption as to what we think they mean.

We need to be curious about what is and what could be. We need to take our time. Reflect. Ponder. Wonder.

*Michelle Gibbings is a Melbourne-based change leadership and career expert and founder of Change Meridian. She can be contacted at [email protected].

This article first appeared atwww.changemeridian.com.au.